Bob Paul was one of the greatest of all frontier peace officers. His extraordinary life of high adventure—first as a whaler in the South Pacific, then as a Forty-Niner in the Gold Rush, and finally as a pioneer lawman and detective in California and Arizona—always seemed to find him in the right place at the right time.

Bob Paul was one of the greatest of all frontier peace officers. His extraordinary life of high adventure—first as a whaler in the South Pacific, then as a Forty-Niner in the Gold Rush, and finally as a pioneer lawman and detective in California and Arizona—always seemed to find him in the right place at the right time.

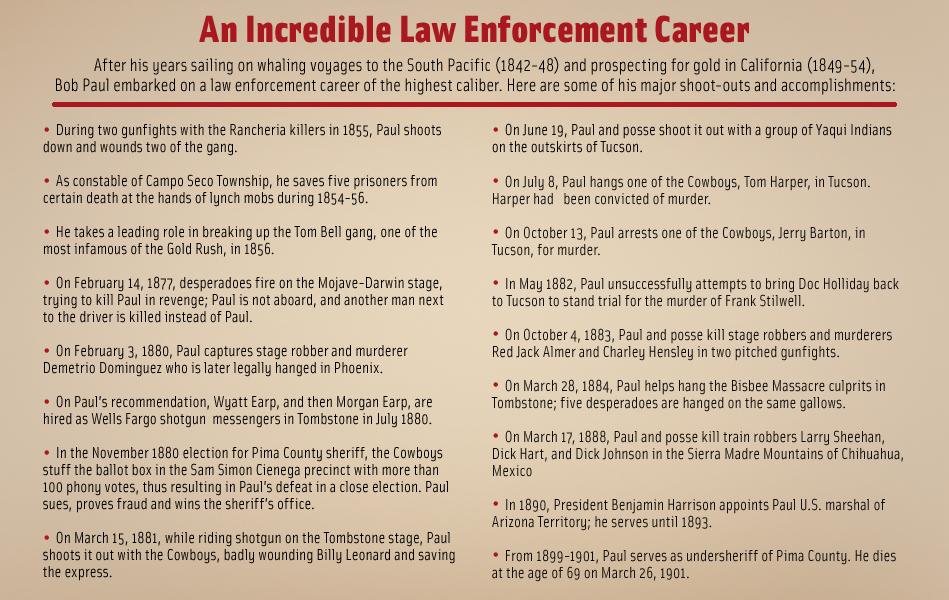

A close friend of Wyatt Earp, Paul is best known today for his important role in Tombstone’s Earp-Clanton feud of 1881-82. But Paul was already a famous lawman when Wells Fargo sent him to Arizona Territory in 1878. His five-decade career as a peace officer began in 1854 during the California Gold Rush and lasted until just before his death in 1901. He fought lynch mobs, tracked down stage robbers, investigated murders, pursued Apaches and jailbreakers, and killed five desperadoes in sensational gun battles in Arizona and Old Mexico.

During that half century of service on two of the West’s wildest frontiers, Paul helped invent law enforcement on the American frontier. His bloody gun battles with the Rancheria killers of the California Gold Rush, more than 25 years before the O.K. Corral gunfight in Tombstone, were as exciting as anything filmmakers could conjure.

Gold Rush Rancheria Killings

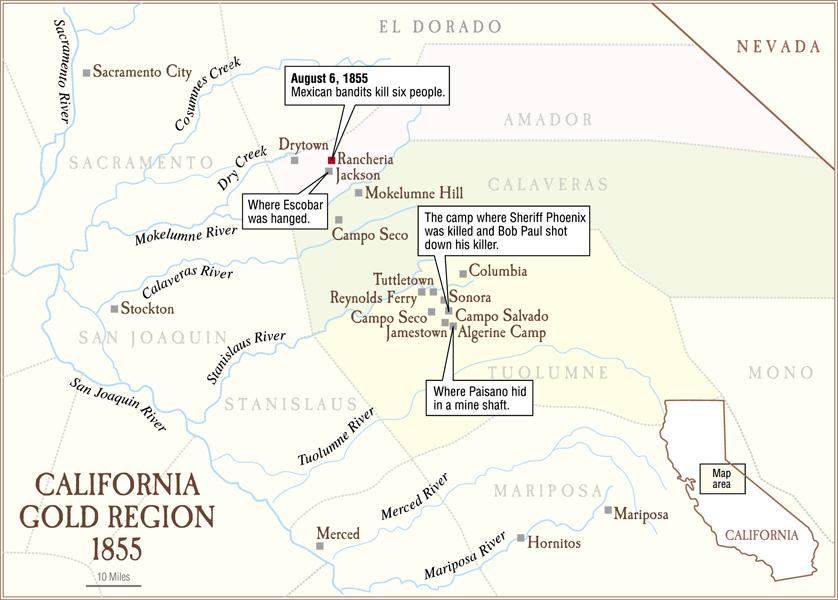

In the summer of 1855 budding young lawman Bob Paul played a prominent role in one of the most important incidents of racial violence in the Gold Rush. It began on a sweltering August 6, when a violent gang of bandidos rode down Dry Creek in Amador County, robbing each Chinese mining camp they came across. The leader was reported to be Guadalupe Gamba, and his followers were Manuel Castro and Rafael Escobar, plus six others later identified only by their first names or nicknames: “Macemanio” (probably Maximiliano), Trinidad, California, Bonito, a Californio known as Paisano, and a red-bearded American named Gregorio, or Gregory. Frightened Chinese reported the raids to Amador County Deputy Sheriff George Durham, who got a tip that the bandits were hiding out near Drytown. At dusk, with Constable J.D. Cross, he made a search of Drytown’s Hispanic quarter, known as Chile Flat. A Mexican woman was inside one of the houses, cooking, and the officers stepped inside and asked her if she had seen the robbers. She answered no, but then quietly pulled back a curtain to show the shadowy forms of several desperadoes who had hidden in a back room.

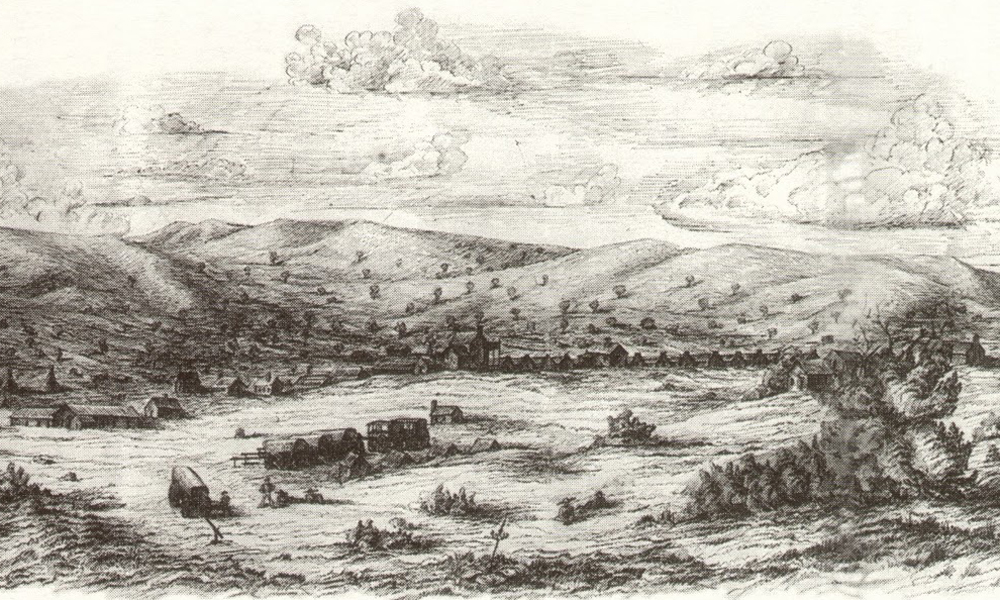

As Durham and Cross backed out, the bandidos broke for the back door and raced for their horses in a corral behind the house. Durham and Cross, six-guns in hand, sprinted after them. At a distance of fifteen steps the outlaws opened up with a thundering barrage of pistol fire. The officers, aiming at muzzle flashes, emptied their revolvers at the robbers, and thought they wounded two of them. After the bandits had fired some fifty shots they leaped into their saddles and escaped. While the two lawmen returned to the Anglo quarter to organize a posse, the bandidos rode three miles southwest toward the little mining camp of Rancheria. The camp had a hotel, store, livery stable, fandango house, and a water-powered quartz mill.

It was night when the freebooters galloped into Rancheria. Tethering their horses, they first stepped into the fandango house to get liquored up. Then, learning that there was considerable cash in town, they poured outside and in two groups simultaneously burst into the store and hotel, shouting “Viva Mexico!” One band entered the hotel, their six-shooters belching flame as they indiscriminately fired on everyone in sight. Several men seated at a table playing cards tried to take cover. A bullet tore Sam Wilson from his chair, killing him instantly. Another card player fell dead in a bloody pool. The hotelkeeper, Michael Dynan, was badly wounded at the bar. His terrified wife, Mary, began shoving their two children out a window when Rafael Escobar shot her in the back, killing her.

At the same time the second bunch of screaming outlaws broke into the Rancheria store. They shot and killed the clerk, Daniel Hutchens, and wounded the owner, Eugene Francis. Though bleeding heavily, Francis struggled with the robbers. A Mexican picked up an axe and chopped at his legs. Francis stumbled out the back door and collapsed. The bandits followed and hacked him to death. For good measure they also killed a local Indian who happened to be sleeping behind the store. The robbers broke open the store safe and stole $6,000. Then, after taking all the horses from the livery stable, they thundered out of town, repeating their battle cry, “Viva Mexico!”

The gang left six dead victims behind. It had been one of the Old West’s most murderous bandit raids. News of the “Rancheria Tragedy” created the wildest excitement. By morning hundreds of miners had poured into Rancheria. The killing of innocent people, including a woman, was beyond the pale, and while some men started in pursuit of the gang, others began rounding up local Mexicans. By afternoon, thirty-six had been herded into a makeshift corral, surrounded by two hundred armed guards. Three of the captives were identified as being with the bunch who had run from the fandango house to the store; one of them had Mary Dynan’s jewelry, and another had her husband’s watch. They gave their names as Puertovino, Trancolino, and Jose. The infuriated mob marched all thirty-six captives to a large oak tree 100 yards east of town. A motion was made that they all be immediately strung up. Cooler heads prevailed, however, and instead Puertovino, Trancolino, and Jose were given half an hour to pray and then were hanged from the tree.

Now the mob turned its fury on Mexicans whom they knew were innocent of the murders. Said one witness, “After the three were hung up, the citizens of Rancheria passed a resolution that no Mexican shall hereafter reside at the place; and every Mexican who shall be found at Rancheria after seven o’clock this evening should be requested to leave, and receive one hundred and fifty lashes in the bargain.” Enraged miners then set fire to the fandango house and all the Mexican jacales (huts) in town. The fire got out of control and threatened to burn the town before it was finally put out. The terrified Mexicans fled and took refuge in nearby Mile Gulch. Local Indians, angered by the death of their compadre and egged on by some of the mob, followed and attacked Mexican men, women, and children in the gulch. At least eight were slain as they tried to escape from the ravine. As one Mexican led his donkey out of the gulch, a trunk of clothes fell from its back. The Indians dropped their weapons, scrambled around the broken trunk, and started donning the clothes. This distraction alone saved the Mexicans from more slaughter. Scattered corpses were later found near the gulch and hogs were spotted devouring bodies. How many were slain was never determined.

Next a mob descended on Gopher Flat, several miles from Rancheria. They had heard a report that one of the bandits was secreted there. He was found in a jacal, under a pile of clothes. Without ceremony, the vigilantes hanged him from a makeshift scaffold formed by a pair of wagon tongues. Then the mob drove fifty Mexicans from the camp and destroyed their homes. Another mob torched Chile Flat in Drytown, burned the Catholic church to the ground, and sent the town’s Chilenos and Mexicans fleeing. The day after the raid, the murdered Indian was turned over to his tribe for burial. Mrs. Dynan and the four Americans were all buried in a common grave. Said one who attended the funeral, “It was certainly a heart-rending spectacle, and many a stony heart gave way.”

While senseless mob violence was engulfing Amador County, its young sheriff, William A. Phoenix, was busy tracking the rest of the real bandits. He first struck a false trail north of Rancheria. Realizing his error, Phoenix led his posse back to Jackson where he found that the gang had headed south and crossed the Mokelumne River into Calaveras County. The sheriff, with George Durham and several other possemen, rode to Mokelumne Hill that night. There they met with Sheriff Clarke and began preparing for a joint manhunt in the morning.

Meanwhile, word of the tragedy quickly reached Campo Seco, twenty-two miles south of Rancheria. The morning after the raid, August 7, 25-year-old Constable Bob Paul heard a rumor that “seven or eight men had been murdered by a band of Mexicans at Rancheria, in Amador County.” This seemed improbable, as one Campo Seco resident explained, “At first the news that such a wholesale murder had been committed was scarcely credited.” But soon afterward a miner came into town from the Mokelumne River and reported that at daybreak he had spotted seven armed riders going up the river. Later in the morning Joseph Petty rode into Campo Seco and reported that a band of seven or eight mounted men were riding south toward the Calaveras River. That was enough for Bob Paul. He and Constable Mark McCormick organized a posse including Petty, Deputy Sheriff “Six-finger” Smith, and David Wells. It took time to obtain good men, horses, and weapons, and it was three p.m. before Paul was ready to start in pursuit.

Spurring their horses, the posse galloped south six miles to Texas Bar on the Calaveras River. There an Italian told them that a local Mexican, Manuel Castro, had been there “and boasted of killing six men and a woman at Rancheria.” Bob Paul and the others raced after Castro. They trailed him three miles down the river but lost his tracks in the rocky terrain. The officers rode on to the Don Manuel rancho where they learned that seven heavily armed horsemen had headed up the Calaveras River. The possemen now retraced their steps, going up the river and returning to Texas Bar, which they reached after dark. There they found Manuel Castro, a six-shooter in each fist, standing defiantly in front of a dance hall.

Constable McCormick stepped up to Castro, told him he was his prisoner, and seized him in a bear hug. With a desperate effort, Castro managed to wrench loose. As he started to run, several of the posse opened fire, but their shots went wide in the darkness. Bob Paul and McCormick, six-guns in hand, raced after him. There were twenty feet between them when the fleeing outlaw threw his revolver over his shoulder and opened fire. Pistol muzzles flaming in the blackness, outlaw and officers exchanged fifteen shots in a running gunfight. Castro fired five times, McCormick four, and Bob Paul “four or five,” according to a witness. Finally one of the constables’ bullets tore into the small of Castro’s back, ripping completely through his body and just missing the spine. The bandido dropped like a stone.

The officers obtained a buggy and brought Castro to a doctor in Texas Bar. The physician opined that his wound was mortal. Castro, who spoke good English, was asked if he wished to make a dying confession. Though in great pain, Castro agreed, and his statement was taken down by the local magistrate and witnessed by the possemen. He said he had met the American, Gregorio, in Hornitos two or three weeks earlier. He gave full details of the Rancheria raid, and identified five of his compadres, saying he could not recall the names of the other two. He claimed that he had not done any of the killing, but had stood guard outside during the raid.

Manuel Castro was a tough character, and it soon became evident that his wound was not fatal. Paul and the others brought their prisoner to Mokelumne Hill and turned him over to Sheriffs Clarke and Phoenix. The Amador sheriff detailed two of his possemen to return Castro to Jackson in a buggy. But no sooner had they appeared on the town’s streets than a huge mob surrounded the buggy and drove it underneath the town’s infamous hanging tree. A noose was already hanging from a limb, and it was fastened around the wounded Castro’s neck. Then the horses were given a slap, the buggy jerked forward, and Castro was left swinging in the shadow of the hanging tree.

Meanwhile Sheriff Clarke, with Bob Paul, Deputy Sheriff Ben K. Thorn, Sheriff Phoenix, George Durham, Six-finger Smith, Constable McCormick, Edward Sherry, and several other possemen set out on the outlaws’ trail. At Jenny Lind they disarmed a large number of Mexicans and interrogated them, learning that the bandidos were camped near Reynolds Ferry on the Stanislaus River. By the time the posse arrived at Reynolds Ferry they found that the gang had fled south toward Tuolumne County. The possemen continued after them, searching Tuttletown, Sonora, and then Campo Seco, a different camp from the one in Calaveras, situated four miles southwest of Sonora. From there, they rode a mile north to Jamestown, where they recovered several of the horses that had been stolen from Rancheria. The animals were half dead from exhaustion, and the lawmen now knew they were pushing the bandits hard.

On the morning of August 12, 1855, Bob Paul and the rest of the posse rode back into Sonora. They found that the killers’ trail led toward the settlement at Campo Salvado, ten miles south, and Clarke, Phoenix, Paul and the other officers decided to search it. The lawmen rode into Campo Salvado at noon and arrested every Hispanic in the camp for questioning. Sheriff Clarke later said that “a more villainous looking set were never seen.” However, Americans in the camp quickly came forward and provided solid alibis, declaring that all the men arrested were residents of Campo Salvado and had been there at the time of the Rancheria raid.

The lawmen were not ready to give up, and split into two parties. One, consisting of Sheriff Phoenix, Durham, Smith, and McCormick, entered a large adobe cantina to search it. Bob Paul and the balance of the posse stood guard at various points around the camp. When a lone Mexican rode in, he was placed under arrest by one of the guards. At his request, several of the posse took him across a gulch just outside of town so he could “obtain proof of good character.” By this time Sheriff Phoenix and his three possemen, having searched the cantina, sat down to take a drink. They spotted a Mexican girl motioning toward someone outside the back door. George Durham glanced outside and immediately recognized three of the gang.

“There they are!” he exclaimed to Phoenix. The sheriff and his men quickly stepped outside and approached the three armed Hispanics. Bob Paul, alerted by the shout, ran toward the cantina in time to see Phoenix seize one of the suspects. One of the possemen cried a warning to Phoenix, “Shoot him—do not try to take him!”

But it was too late. The Mexican jerked loose and pulled his revolver. He and his compadres raced behind a picket fence, then all three wheeled to face Sheriff Phoenix. One bandido, the Californio known as Paisano, opened fire at close range, shooting the sheriff through the heart. As Phoenix went down, he managed to get off two pistol shots, slightly wounding one of the Mexicans. By now all the desperados had their six-shooters out, one of them with a revolver in each fist. Bob Paul, in one fluid movement, whipped his six-gun from its holster, thumbed the hammer, and took dead aim at Paisano. His weapon boomed and a pistol ball tore into Paisano’s chest. Then Paul emptied his six-shooter on Paisano. The killer dropped into the dusty street, apparently dead, his neck and chest perforated by pistol balls. At the same time, Durham, Smith, and McCormick opened up with their revolvers, and another of the desperadoes dropped in a hail of six-gun fire, riddled with fatal bullets.

The third bandit, flourishing both six-shooters, fled into a nearby tent with the lawmen in pursuit. The gunfire brought the balance of the posse racing back into town. They surrounded the tent, but the outlaw kept them at bay with his pistols. Finally the officers decided to fire the tent and those adjoining it. As the flames burst forth the bandido rushed out, shooting as he came, right hand, left hand. The lawmen fired back, hitting him twice, but the wounds did not slow him down. When his revolvers were empty the desperado used them as clubs, fighting the officers like a tiger. Finally one of the lawmen, whose weapons were also empty, seized an axe and hacked him to death.

Now the officers realized that the man Bob Paul had shot was not dead. During the excitement Paisano had crawled off into the chapparal and disappeared. Sheriff Clarke and the rest of the posse left the two dead bandits to be buried in Campo Salvado and brought Phoenix’s body into Sonora the following morning. There he was laid to rest that afternoon by the Masonic fraternity. At five o’clock, just after the funeral, Clarke, Paul, and the rest started out after the balance of the gang. They were unable to find the wounded Paisano, but picked up another suspect and headed back toward Calaveras. Passing through Columbia the next morning, August 14, they learned that local citizens had rounded up a dozen suspicious Mexicans. One of them, Rafael Escobar, had been found sleeping under a tree, with two large six-guns under his blanket. Constable John Leary, an experienced lawman who had fought the Joaquin Murrieta band in 1852, identified him as a compadre of Joaquin’s. Sheriff Clarke and his posse were asked to visit the Columbia jail and look over the suspects.

George Durham immediately identified Rafael Escobar as the man who had slain Mrs. Dynan. Escobar admitted to Sheriff Clarke “that he belonged to the gang, and was at Rancheria—that they had all taken an oath to die rather than expose each other.” Clarke, Paul, and the posse brought the bandido into Mokelumne Hill and lodged him in jail for the night. In the morning George Durham bundled Escobar into a buggy, and with several of the posse as a guard, started for Jackson. Once there, the scene involving Manuel Castro was repeated. An enraged mob surrounded the buggy and drove it under the hanging tree. An American who spoke Spanish was appointed to interrogate Escobar. Now he claimed that although he knew the members of the gang, he had not participated in the Rancheria Tragedy. He provided the first names and nicknames of four of the killers.

The mob was determined to make him confess, as Jackson’s newspaper editor reported: “The Mexican was ‘run up’ and held there for a short time, then lowered, when great difficulty was encountered getting the rope loosened from his neck. It was finally cut loose; in the meantime, he suffered excruciating pain, rolling his eyes about, throwing his head and body about at random, and making a loud gurgling noise with his throat. When the rope was taken from his neck he revived and asked for brandy and water and said he would like to talk, but it was no use, as the people would believe nothing he said, and he wished they would kill him outright. . . . He said if the Americans would arm themselves and take him with them he could point out every man that was connected with the Rancheria affair.” But by this time the crowd would have none of it. They began to yell, “Run him up!” This was done, and Escobar was left dangling from the tree. A local photographer took a daguerreotype of the scene, which has long been lost, but a lithograph made of the image still exists. Rafael Escobar was the tenth and last man to die on Jackson’s infamous hanging tree.

Paisano had managed to survive the wounds inflicted by Bob Paul, for the gunpowder used in that era did not have the punch of modern weaponry. On August 27 an old Mexican came into Sonora and reported that the badly wounded desperado had come to his house in Algerine Camp for assistance. When Paisano threatened to kill the viejo if he did not help him, he hid the desperado in a nearby mine shaft. George Durham and a posse accompanied the Mexican to Algerine Camp, where they approached the shaft and ordered Paisano to give himself up. The bandido responded that he “had five shots for the Americans and one for himself.” The possemen then stuffed the shaft with dry brush and set a match to it. As the tunnel filled with smoke a single pistol shot rang out. Paisano had committed suicide rather than surrender. When the fire died down, they dragged out his body, which plainly showed Bob Paul’s bullet wounds in the neck and chest.

Two more suspects—names unknown—were captured in Sonora in early September. They were brought to Jackson and given a vigilante trial on September 8. Strong evidence against them was presented, and both confessed their guilt. The next morning they were brought to Rancheria and publicly hanged before a large throng. These were the last deaths in the Rancheria Tragedy. At least twenty-five people had been slain. For sheer brutality and senseless violence, both by Hispanic bandidos and Anglo mobs, it had few equals in the Gold Rush.

Offsetting the mindless brutality of the mobs, which punished the innocent as well as the guilty, were the lawful actions of the officers. They had diligently trailed the real killers and attempted to take them alive. Both Constable McCormick and Sheriff Phoenix had physically seized two of the armed outlaws, and Phoenix paid for his compassion with his life. Bob Paul and the rest only fired on the bandits after they were shot at first. The officers did not kill their captives, but instead brought them to Jackson to face criminal charges, where they were overwhelmed by mobs and their prisoners lynched. Bob Paul’s courage in helping track down the killers, and in shooting two of them who resisted arrest, was recognized by the voters of Campo Seco. In the election that month Bob Paul was re-elected constable of Campo Seco. It was but the beginning of an extraordinary career on two of the West’s toughest frontiers.

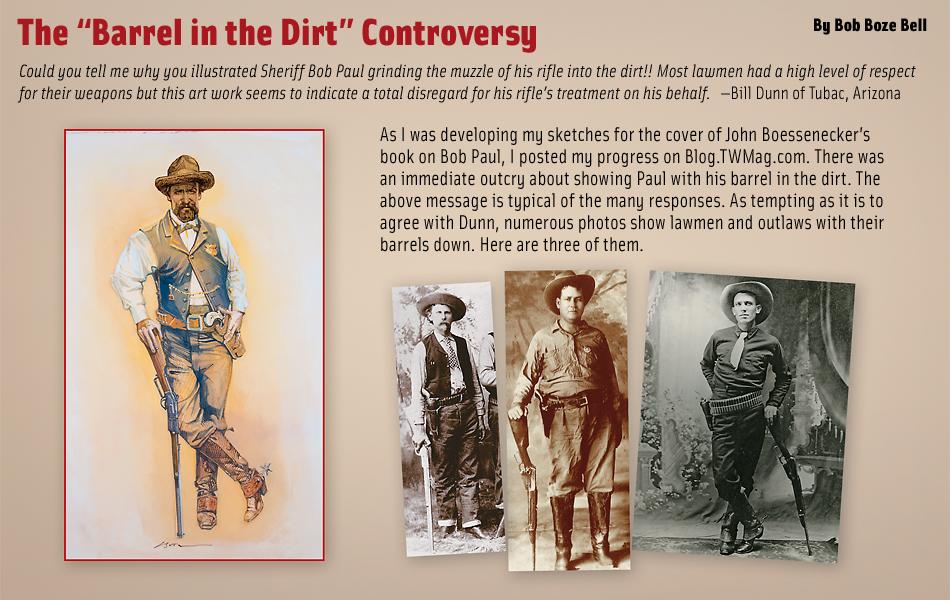

This feature is an excerpt from John Boessenecker’s book, When Law Was in the Holster: The Frontier Life of Bob Paul, due out from the University of Oklahoma Press this October.

Rafael Escobar lynched on Jackson’s notorious hanging tree, August 15, 1855. This lithograph is an exact copy of a lost daguerreotype.

– Courtesy William B. Secrest –