They call it “the richest hell on earth.”

They call it “the richest hell on earth.”

Excuse me … hill, not hell.

I’m on that scenic and historic stretch of Interstate 90 in Montana’s “Gold West” Country, showing my bias against “mining” and for “ranching.” But I’ve been asked to stop in at Butte and give it a chance. Butte always gets kicked around in Montana as the butt of travel jokes (i.e., What are the two prettiest sights in Montana? The Flathead in the spring, and Butte in your rearview mirror).

If you’re interested in mining, few American towns have a lode richer than Butte’s. That’s evident at the Mineral Museum, the World Museum of Mining and Hell Roarin’ Gulch and, for the more modern miner, the Berkeley Pit, an open-pit copper operation that produced better than 290 million tons of copper between 1955 and 1983.

Butte emerged in the 1870s, but it has always had a rough history. That’s the way things go in the topsy-turvy world of mining. In 1879, a fire swept through the central business district, so the city council required that all new buildings, in what’s known today as “Uptown,” be constructed of brick or stone.

Thus, Butte stands like Montana’s version of a Charles Dickens city—tough and foreboding, only heavy on the Irish pubs (that’s a good thing). You can see the opulence of the mining world at the Copper King Mansion, a three-story, 34-room gem that was once the home of copper magnate and politician William A. Clark and is now a charming bed and breakfast. You can also feel the tragedy of the mining world at the Granite Mountain Mine Memorial, which honors the 168 men killed when a fire swept through the connecting mines in June 1917—the deadliest disaster in metal-mining history.

I’m having a change of heart. The bias against “mining” fades away as I leave Butte with a newfound respect for this town, its food (don’t miss the Downtown Cafe!) and its preservation of history.

Down the road lies Deer Lodge, which, the way I figure it, should be the ranching capital of America. But while Butte is overshadowed by an often tragic history, Deer Lodge is known as the home of the Old Montana Prison Complex, where the Montana Territorial Prison started taking lodgers in 1871. Want a horsehair-hitched belt made by inmates? This is the place.

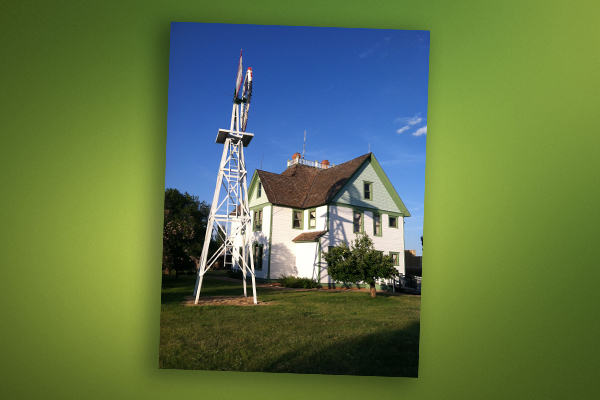

Since that stretch in Angola, however, I’ve tried to avoid prisons. I’m here to check out the Grant-Kohrs Ranch, the only National Historic Site that doubles as a working cattle ranch. Johnny Grant established his spread in the 1850s, and that ranch grew into a 10 million-acre cattle kingdom. Carsten Conrad Kohrs bought Grant’s home ranch in 1866, and eventually the ranch was shipping some 10,000 head of cattle to Chicago.

Today’s scenic ranch has been reduced to a mere 1,600 acres, but you’ll find 80 historic structures, including “bunkhouse row,” barns and homes. Plus, each summer (July 28-29 this year), the ranch plays host to “Western Heritage Days,” offering visitors up-close-and-personal looks, through guest speakers and re-enactors, at the Open Range era: roping, branding, grub, cowboy music.

Yet ranching isn’t all glory. It can be as precarious as mining, and Grant-Kohrs provides a pretty grim overview of the end of the Open Range.

Ranches and herds grew in the mid-1880s. Pastures were overgrazed. Then Mother Nature struck back with the terrible winter of 1886-87, which wiped out an estimated one-third to one-half of Northern plains cattle.

So, mining vs. ranching … who wins?

For history’s sake, thanks to Butte and Deer Lodge, they both do.