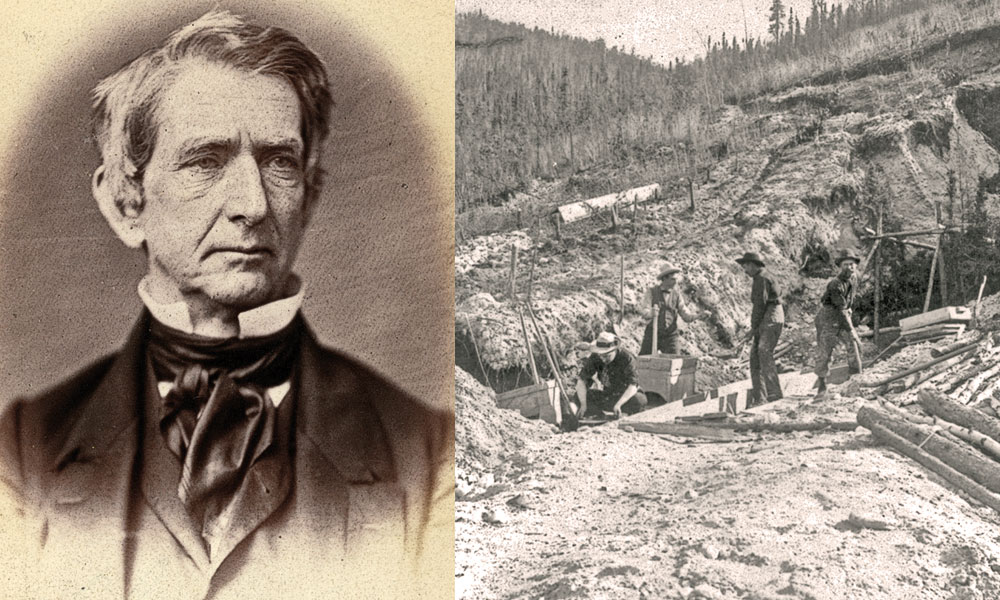

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

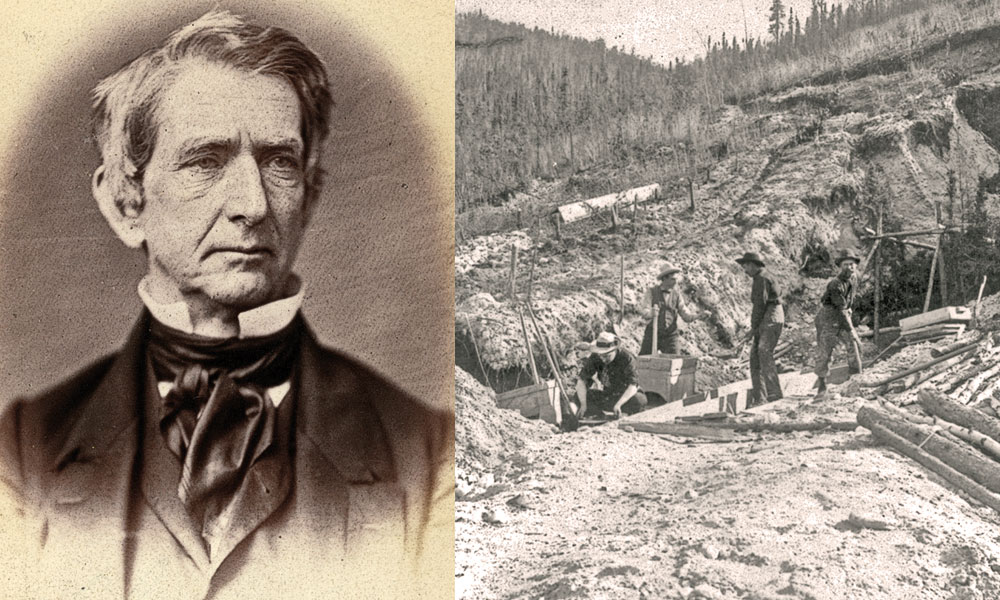

As early as 1852, New York Sen. William Seward saw the possibilities of the frozen land far to the northwest of the United States.

Well, maybe not the land. But just off the coast, the seas were teeming with whales, which provided lamp oil and blubber. It was an idea for the future, when Seward—who had aspirations for a much higher office—might have the power to pull off a deal.

Seward never forgot about the land its Russian owners called Alaska.

In 1864, while U.S. secretary of state, Seward heard reports that the Russians might take offers for Alaska. Russian diplomat Eduard de Stoeckl favored the move; he thought Americans would eventually overrun the place anyway, much as they had Texas in the 1830s. The timing was still not right though, not with the U.S. fighting the Civil War.

But by early 1867, Seward and Stoeckl reached a meeting of minds and of pocketbooks. The two diplomats struck a deal that would transfer Alaska to the U.S. for $7 million (later upped to $7.2 million). President Andrew Johnson’s cabinet approved a draft for the purchase on March 15; the U.S. took possession on October 18.

There was just one little catch. Cash. The House of Representatives had yet to appropriate the purchase money. Some, even within his own party, hated President Johnson for his Reconstruction policies. He was about to be impeached for firing War Secretary Edwin Stanton—so his administration was getting extra scrutiny.

Seward wined and dined the lawmakers, but his poor health jeopardized his efforts. He’d been severely hurt in a carriage accident in April 1865, then he was wounded days later in an assassination attempt tied to the murder of President Abraham Lincoln.

In 1867, Seward was 66 years old and struggling. He “speaks and thinks slowly, repeats himself, gets wound up and doesn’t seem to have a clear idea of what he is after,” his friend Charles Francis Adams Jr. said.

But Seward had tricks up his sleeve…or so it appeared. He reportedly told two friends that the Russians had bribed several prominent congressmen. He later denied it under oath, but he may have perjured himself to seal the deal. The House finally came up with the money in July 1868.

Seward visited Alaska in 1869 during a grand tour of the West. Again, he proved to be a prophet—suggesting that people would vacation there to enjoy the scenery.

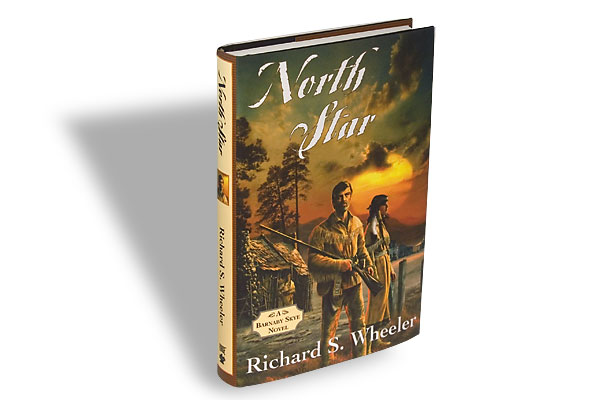

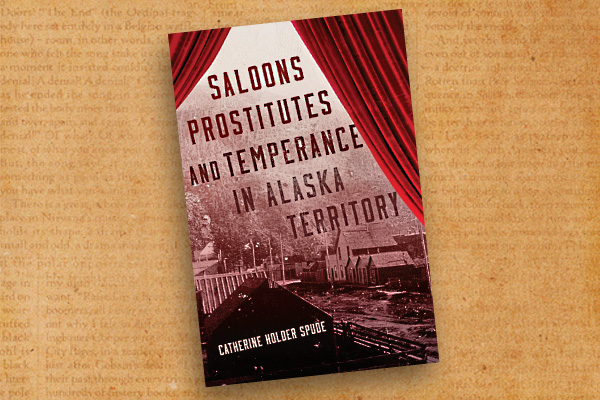

The purchase was mocked by some as “Seward’s Folly.” Years passed before the Klondike and Alaska gold rushes brought development and riches to the region—and before the Wild West moved there in the forms of Wyatt Earp, Soapy Smith and gunman Frank Canton. Seward, who died in 1872, never saw Alaska’s wildest days.