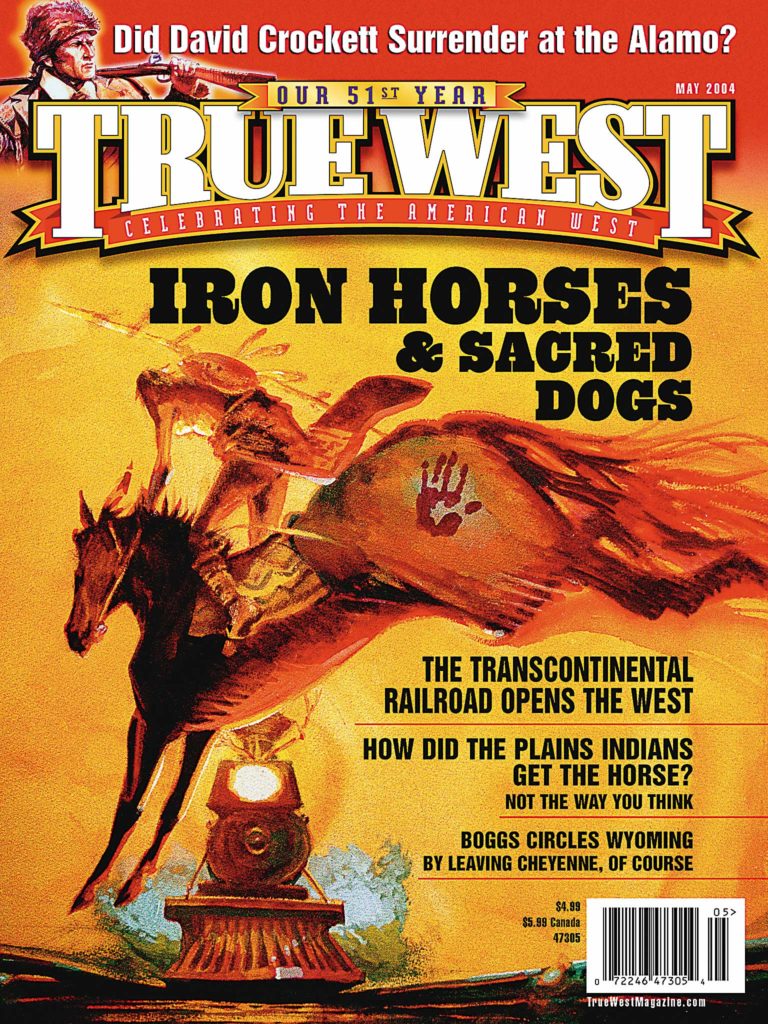

It’s Monday, May 10, 1869, 2:40 p.m., Eastern time. For the first time, the entire nation is riveted to one event.

It’s Monday, May 10, 1869, 2:40 p.m., Eastern time. For the first time, the entire nation is riveted to one event.

“We have got done praying, the spike is about to be presented,” W.N. Shilling taps out in Morse code.

Tens of thousands of people across the nation stand by for the country’s first telegraph “hookup.”

In a nation that had just gone through a wrenching Civil War and the assassination of the president who’d set this moment in motion, the message brought new hope. “Lee’s surrender four years earlier had signified the bonding of the Union, North and South. The Golden Spike meant the Union was held together, East and West.”

Those words, by the late historian Stephen Ambrose, speak to the monumental happening that Monday afternoon as the final spike was driven to complete the world’s first transcontinental railroad.

In his book, so aptly named, Nothing Like it in the World, Ambrose wrote: “Across the nation, bells pealed. Even the venerable Liberty Bell in Philadelphia was rung. Then came the boom of cannons, 220 of them in San Francisco at Fort Point, a hundred in Washington D.C., countless fired off elsewhere. It was said that more cannons were fired in celebration than ever took part in the Battle of Gettysburg. Everywhere there was the shriek of fire whistles, firecrackers and fireworks, singing and prayers in churches. The Tabernacle in Salt Lake City was packed to capacity, with an astonishing seven thousand people. In New Orleans, Richmond, Atlanta, and throughout the old Confederacy, there were celebrations. Chicago had a parade that was its largest of the century—seven miles long, with tens of thousands of people participating, cheering, watching.”

It would take exactly a century before Americans would again feel that same sense of awe, when man first walked on the moon in 1969.

A colossal moment like that helps define a nation, which is exactly what was happening that cold day in the middle of the 19th century when America conquered the continent as the east and west rails of the railroad finally met.

The fire-breather shall build an empire

In 1800, when Lewis and Clark first explored the vast lands beyond the Mississippi River, nothing in the world moved faster than a horse, and everyone was convinced nothing ever would. America then was a slim, coastal republic of five million people, but swift growth and stunning technology were right around the corner. By 1828, work began on the first railroad in the East, and just four years later, Congress was asked to finance a transcontinental railroad between New York City and San Francisco, California.

Congress laughed. Everyone laughed. It was impossible. It was a folly. There were too many impediments.

“One of the largest nations on earth by 1853, when the ink dried on the Gadsden Purchase Treaty, the United States had a population of some 24 million, burgeoning through tremendous natural increase and massive drafts of European and African immigration,” writes John Hoyt Williams in A Great & Shining Road. “This growing population—energetic, brawling and often visionary—was still, however, closely tied to the coastal plains, seemingly forever halted by the ice-tipped crags of the Sierra Nevadas in the West and the turgid Mississippi River in the East: a nation severed by topography.”

And in between was a great void that maps simply designated “The Great American Desert.” What most Americans knew of that void was that it was filled with “hostile Indians” and uncounted millions of buffalo; that it was treeless and unsettled; and that it was overrun with insects and snakes. It’s not hard to imagine how dark and forbidding that sounded to most Easterners.

But there’s nothing like gold to change people’s minds, and when gold was discovered in California in 1848, it became very important to traverse that dark, forbidding, hostile desert to get to the riches.

Congress quickly stopped laughing and started fighting over where the coast-to-coast railroad should be laid. Tensions were brewing that would erupt into the Civil War as Northern and Southern senators fought to wrest control of America’s population and economic growth. Southerners would never approve federal money for a Northern route; Northerners felt the same way about a Southern route. It was only after Southern senators rushed home in the spring of 1861 to support the Confederacy that Northern senators were able to pass a bill creating the railroad in their own neighborhood.

President Abraham Lincoln happily signed the Pacific Railroad Act on July 1, 1862, citing national defense as its prime objective (although the motivating factor for years had been to open up trade). That year, Congress also passed the Homestead Act that would open up the West for settlement. (And is it ironic or prophetic that during the same year, French scientist Leon Foucault first measured what everyone thought was immeasurable—the speed of light?)

Americans were now poised on the brink of a challenging, exciting idea, and they wouldn’t take time to worry or notice the terrible price that would be paid by the people the plan exploited and displaced. Nor would citizens account for the greed, corruption and racism that haunted the project.

This was a race—a race with one team starting from the east and working west, the other from the west working east—and with it went the determination to fulfill a concept called Manifest Destiny: it was the government’s God-given right to inhabit and control the entire continent.

“A fast track to the goldfields seemed crucial, not only for individual gold seekers but also for the government,” notes Rhoda Blumberg in Full Steam Ahead: The Race to Build a Transcontinental Railroad. “Trains racing cross-country could quickly transport California’s wealth to Washington. Also, soldiers and supplies could be speedily shipped to western military posts that had been established to stock provisions for travelers and protect the country from ‘wild Indians.’”

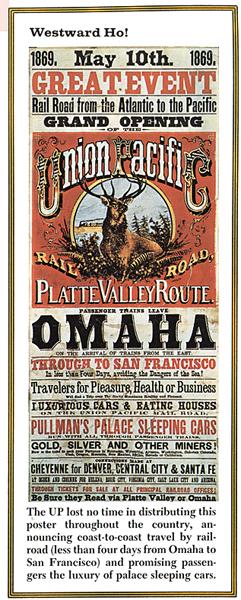

From the west, the Central Pacific Co. was granted the right to lay tracks from Sacramento, California, east. From the east, the new Union Pacific Co. started at Omaha, Nebraska, to lay tracks west. Where they were to meet wasn’t even determined: each company was paid by the government for every mile of track they laid, and they were simply told to build.

Not everyone was happy the federal government had embarked on this massive project. Some didn’t like trains at all and considered them loud, smoke-belching, “topsyturvy, harum scarum, whirligig mechanical demons.” Existing transport businesses, from riverboats to stagecoaches to freight companies, didn’t welcome the competition.

Nobody asked the Indians what they thought, even though the tracks would be laid across land that was deeded to various tribes. Lincoln’s signature allowed the federal government simply to steal all the Indian land it needed. The idea was popular, and a horrible pun on “Injun” summed up the white attitude: “Little Indian Boy, Step Out of the Way for the Big Engine.”

I’ve been workin’ on the railroad

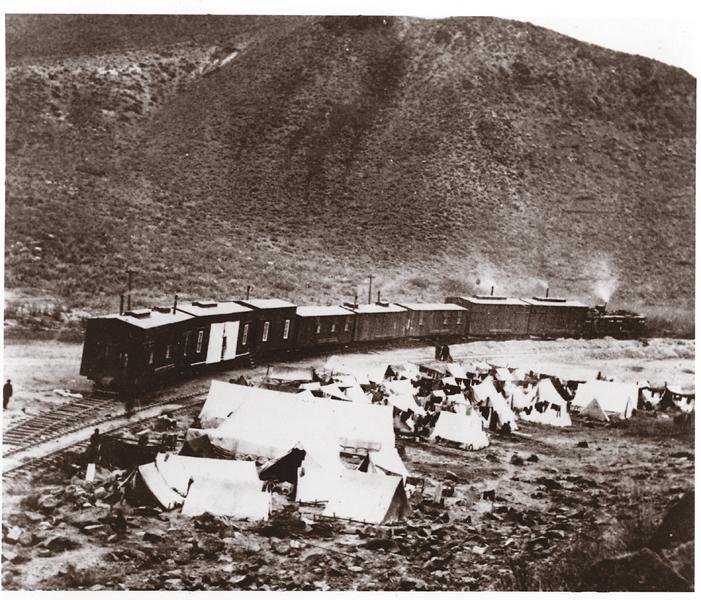

“As the tracks crept across the vast wilderness west of the Missouri River at about two miles a day they took with them a town and a gang known as ‘Hell on Wheels,’” reads a “brief history” by the Union Pacific Railroad. “This name was popularly associated with the construction crews and their hanger-on friends who arrived on the first train into the new ‘end of track’ towns which sprang up every few miles…. Shacks, tents, furniture and personal belongings and even complete weekly newspaper plants were brought in by the gangs…. Gamblers, saloon keepers and other gun-toters joined the ‘Hell on Wheels’ group all along the line, taking advantage of the golden opportunity to help workers spend their hard-earned cash.”

Government bonds had been pledged for each mile of track, plus the railroad companies got land grants on either side of the tracks—first 6,400 acres per mile, then double that in an 1864 amendment.

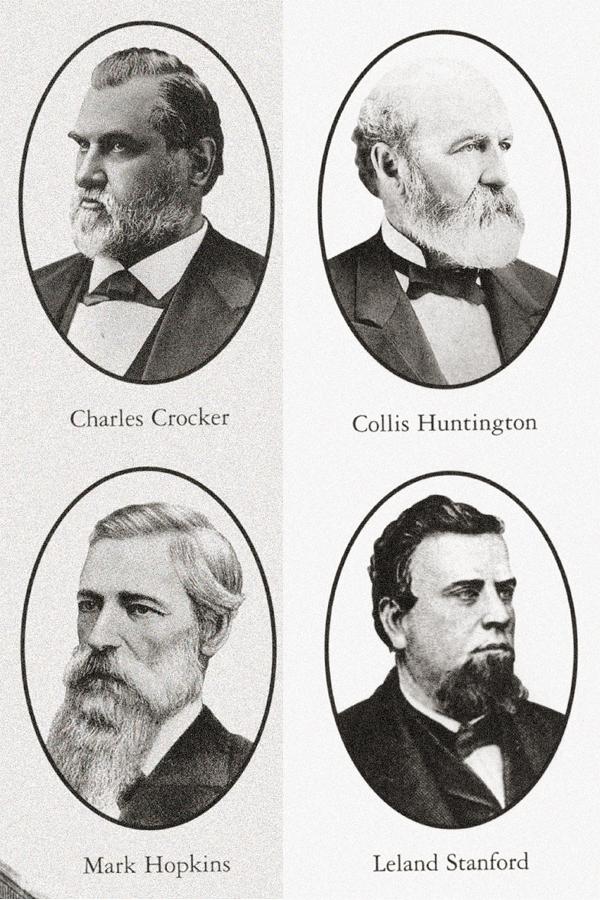

In California, “The Big Four” ran the show and found they had their own private gravy train. These men’s names live on in history, and many would prefer to forget the sleazy ways they got filthy rich.

The four had all started out as shopkeepers, owning hardware, dry goods and grocery stores. But they quickly saw the value of a railroad that could take their merchandise to the mines of Nevada, where gold and silver were making people rich overnight.

Leland Stanford was then the governor of California (and is the namesake for one of the nation’s finest universities). He earmarked more than a million dollars of state money for his Central Pacific Railroad. His partner, Collis Huntington, paid off a geologist to lie about the location of the Sierra foothills, thereby collecting three times more in government fees for building on a “mountain” rather than flat land.

Along with Mark Hopkins and Charles Crocker, the Big Four created their own construction business, then hired themselves to work for their own railroad company at inflated prices, paying themselves $90 million for labor and materials that cost them only a third of that.

The company broke ground on the west to east leg of the railroad on January 8, 1863, but in the first 13 months, it had laid only 18 miles of tracks. Labor was a continual problem—finding it, keeping it—because digging for gold was still a big lure. In desperation, the owners turned to Chinese workers; “coolies” was the derogatory name they were called. But Chinese workers would end up dominating the Central Pacific crews—more than 6,000 would eventually hire on—and they get credit for building most of this leg. The Chinese were paid less and kept segregated from other workers (who at first were angered and then mortified by how efficient and effective the Chinese workers were).

From Omaha going west, the railroad was being built by the Union Pacific Co., which relied on Irish emigrants, blacks, Indians, scouts, teamsters and hunters. (When the two legs eventually met, Irishmen from the Union Pacific laid the second to last rail, while Chinese hands from the Central Pacific laid the last.)

The east to west leg broke ground on December 2, 1863, but work didn’t start for three more months, and even when it did, nothing really got built for all that year or most of 1865.

The Union Pacific was owned by investors headed by Thomas Durant of New York City, who created, much like their counterparts in the West, their own construction company to work for their own railroad. Durant “had no grand patriotic visions about binding the nation together,” Blumberg writes. “A transcontinental railroad was merely his private road to riches.”

But when things got moving, as many as 15,000 men worked on each leg, almost the size of Civil War armies. None of them felt they’d been done right by their employers, and hundreds would be killed on the job. Some 2,000 Chinese workers went on strike for equal wages. Justice failed when black replacements were shipped in. Irishmen sang of misuse and abuse: “Our boss’s name it was Tom King,/ He kept a store to rob the men;/ a Yankee clerk with ink and pen,/ to cheat Pat on the railway.”

In fact, the momentous joining of the two legs was held up by a day because Union Pacific workers stopped the train carrying Durant to the ceremony, demanding back pay. They chained the wheels to the track and wouldn’t move until they had cash in hand. If that wasn’t bad enough, Durant’s train was delayed a second time because a rickety bridge his crews had built was further weakened by rain. Everyone feared it would collapse. (It wasn’t the first or last problem with soddy workmanship as companies were paid for each mile with apparently no oversight to quality of work.) But perhaps the most blatant ripoff was the 290 miles of duplicate tracks the two companies built in sight of each other, determined to avoid meeting as long as possible since they were being paid $32,000 per mile. By the time someone from Washington discovered the scam, almost $9.3 million in government payments had been claimed.

There were problems every step of the way. If it wasn’t the brutal winter, it was the solid granite that stood in the way; if it wasn’t the lack of workers, it was hostile Indians.

“The Plains Indians saw tracks being laid on hunting grounds that treaties had promised were to be theirs forever,” Blumberg notes. “They watched trains whose clangs and shrieks frightened away their game. They witnessed the wanton slaying of their sacred buffalo by sportsmen who enjoyed shooting, then left the animals to rot. Threatened with starvation, extinction or incarceration on loathsome reservations, they fought back.”

But of course, that’s not how white Americans saw the Indian attacks in those days. They saw them as moments of terror by “savages” who were in the way and needed to be exterminated at best, or caged at least, for everyone else’s safety.

At the same time, newspapers kept the nation whipped up with every new mile of track. “Readers, riveted with suspense, avidly followed news about America’s great railroad race, as though they were checking out championship sports scores,” Blumberg notes.

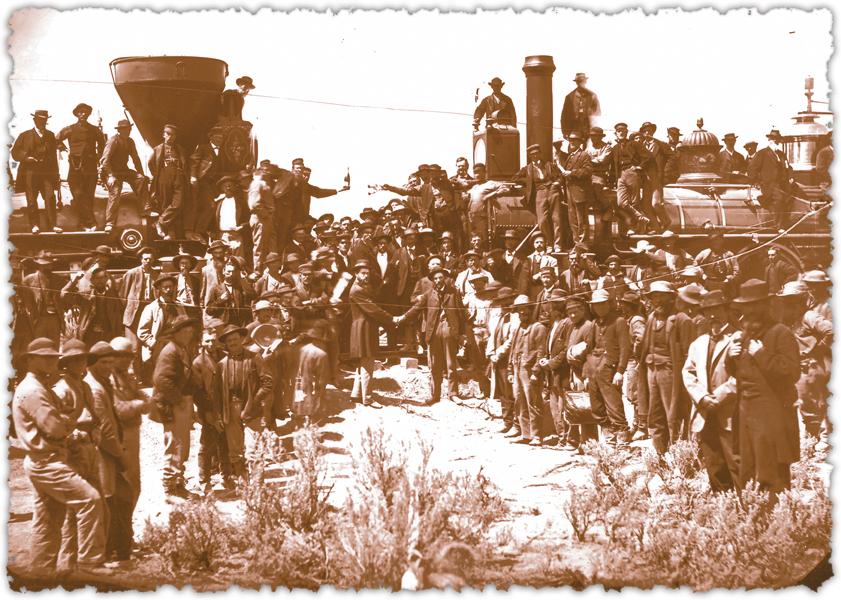

By the time the meeting point was set for Promontory Summit in Utah—a barren spot north of the great Salt Lake—a total of 690 miles of track had been laid from Sacramento and 1,086 track miles had been laid from Omaha.

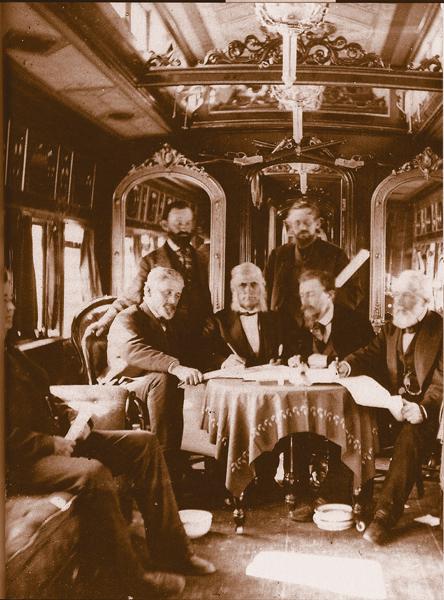

On May 10, 1869, just a 56-foot gap remained as officials from both railroads—Durant finally arrived two days late—gathered for the moment the nation now awaited.

In the final ceremony, there were actually several spikes: from Nevada came a spike of silver from the Comstock Lode; from Arizona, a spike of gold, silver and iron alloy; spikes of silver and gold came from Idaho and Montana; while California was given the honor of the official golden spike fashioned from about $400 worth of gold. On one side was inscribed, “May God continue the unity of our Country as this Railroad unites the two great Oceans of the world.”

The final rail tie was eight feet long, eight inches wide and six inches thick. It was made of highly polished California laurel.

California Gov. Stanford had the honor of driving the last spike. He took the silver-headed maul, swung and … missed. He politely stood aside and handed the mallet to Durant, who some say imitated the miss in order to spare his competitor further embarrassment. (But others say spectators that day felt the misses proved those “high-toned city swells didn’t know how to hit a nail on the head,” Blumberg reports.)

When the spike was finally driven in, the champagne flowed in Utah as the nation went nuts with joy.

“The building of the road was compared to the voyage of Columbus or the landing of the Pilgrims,” Ambrose noted. “It was said that the road was ‘annihilating distance and almost outrunning time.’”

Yes, people in the 19th century liked to talk in hyperbole, but even if it sounds like an exaggeration today, it definitely wasn’t then. Even Ambrose admitted that, “Next to winning the Civil War and abolishing slavery, building the first transcontinental railroad … was the greatest achievement of the American people in the nineteenth century.”

One simple fact demonstrates its impact: before the railroad linked the two sides of the country, it took months and upwards of $1,000 to get from New York City to San Francisco. After the railroad, it took seven days and a first class ticket cost $150.

As Blumberg puts it, “The Union Pacific and Central Pacific had opened up a new West. Their race became part of the American legend, and it set the stage for a new era of expansion. Railroad workers had proved that neither mountains, nor snows, nor deserts could keep the country from going forward, full steam ahead.”

Photo Gallery

As heads of the new Central Pacific line, the most important men around were known as the Big Four. On April 30, 1861, Leland Stanford became president; Collis Huntington, vice president, Mark Hopkins, treasurer; and Charles Crocker, construction supervisor.

The Pacific Railroad Act of 1862, signed by Abraham Lincoln, specified that the Central Pacific would begin laying tracks in Sacramento, California, and work toward the California-Nevada boundary. The act also called for the formation of the Union Pacific, which would start building at the Mississippi River and continue west.

The only member of the Big Four to see the two trains meet was Leland Stanford. Given the honor of driving in the golden ceremonial spike, Stanford swung his silver-headed maul and missed. But the telegrapher still transmitted, “Done!” From an illuminated ball dropping at the capitol dome in Washington, D.C. to a banner waving in San Francisco, California, proclaiming “California Annexes the United States,” everywhere people celebrated the railroad joining the East to the West.

– All photos True West Archives –

The Golden Spike rests today in the Stanford University Museum in Palo Alto, housed in the California university named for one of the men who had helped build the transcontinental railroad, Leland Stanford. Other precious spikes used in the joining ceremony are housed in the Union Pacific Museum in Omaha, Nebraska.

The last tie, however, was destroyed in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire.

Eventually, the railroad was rerouted. Today, it no longer passes through Utah’s Promontory Summit. In 1942, the abandoned rails there were taken apart to provide scrap metal for the nation’s war effort. Today, the spot is a national historic site that features a monument and 1880’s replica rails.

While the Union Pacific crews got nationwide kudos for laying an astonishing 81⁄2 miles of track in one day, Charlie Crocker from the competing Central Pacific line vowed to outdo them, and in fact, his crews did: they laid 10 miles of track on April 28, 1869.

Crocker knew his competitors couldn’t top him because at that moment, there weren’t 10 miles of track left to lay before the two legs of the railroad would meet at Promontory Summit.

In all, the transcontinental railroad was built with 6.25 million ties and 50,000 tons of iron rails and fittings.