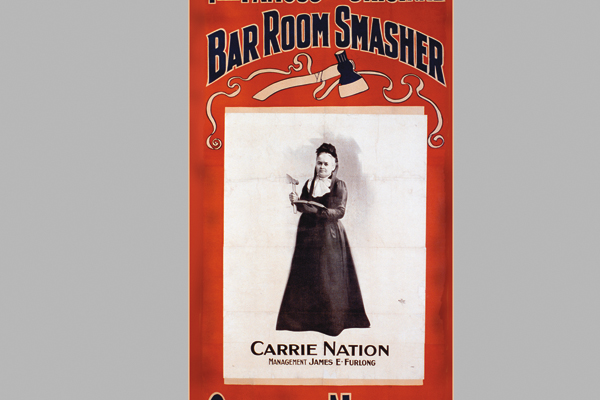

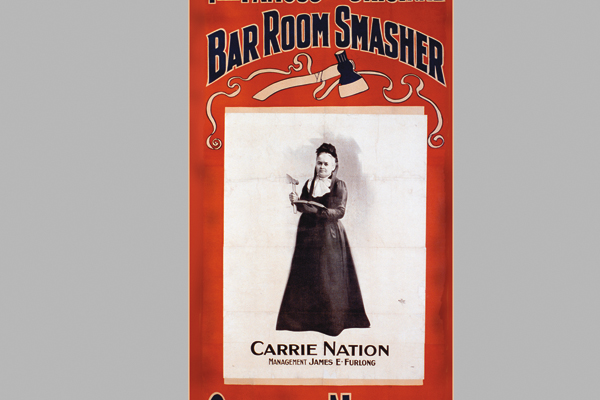

She so believed the Lord picked her to “Carry A. Nation” into Prohibition, this ax-wielding, saloon-destroyer changed the spelling of her first name.

She so believed the Lord picked her to “Carry A. Nation” into Prohibition, this ax-wielding, saloon-destroyer changed the spelling of her first name.

To this day, the woman originally born Carrie Amelia Moore is remembered lovingly as a prohibition crusader, or crudely as a battle-ax.

In her own eyes, Carry Nation was “a bulldog running along at the feet of Jesus, barking at whatever He doesn’t like.”

Her inflammatory actions and words made it clear what she thought He didn’t like. As The Los Angeles Times has reported, “Nearly two decades before Prohibition took effect in 1919, her name and likeness appeared, mockingly, on cocktail napkins, as well as on such items as sugar packets.

The souvenirs condemned or honored

her campaign against the evils of ‘demon rum,’ tobacco, corsets, short skirts and masturbation.”

From the day she smashed up her first saloon on June 1, 1900, in the small Kansas town of Kiowa (she said a voice told her to go there), until her death on June 9, 1911, she boldly fought her cause—sometimes to the chagrin of other prohibitionists. She didn’t care; She was totally committed to her technique, which she called “hatchetation.”

She had her reasons

Carrie was born November 25, 1846, in Kentucky, as the eldest child of a prosperous farmer and an insane mother who, at times, believed she was Queen Victoria.

Carrie, as she always signed her name until she decided another spelling was more potent for her cause, was a sickly child and spent much of her time with her father’s slaves, reading the Bible.

In 1867, she fell in love and married a physician named Charles Gloyd, but he proved to be an alcoholic who couldn’t support his family. The couple had one daughter, but the two had separated by the time she was born. Little Charlien would grow up to be “afflicted,” and her mother always blamed the father’s drinking as the cause. Gloyd himself died, leaving his estranged wife and daughter destitute. Carrie would later credit her situation as an underpin for her crusade.

Carrie taught school for awhile (apparently, not very successfully) and eventually ran a boardinghouse until she remarried. In 1877, she wed David Nation, who was an attorney, minister and news-paper editor nearly 20 years her senior. They settled in Medicine Lodge, Kansas, in 1889—a fortuitous selection, since Kansas was the first state to prohibit alcoholic beverages in its state constitution. But even though that law was nine years old by the time the Nation family arrived, Carrie soon discovered saloons, or “joints,” were thriving.

At first, she concentrated on civic and religious work, and was so generous, she was known as “Mother Nation,” according to the Kansas State Historical Society online exhibit on Carry A. Nation. But all that would change drama-tically. “By 1899 Nation was directing much of her energy towards temperance matters. She worked with other members of the local Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) to close seven illegal liquor outlets through non-violent means. Sometime during the spring of 1900, however, she turned to more aggressive methods,” writes Robert Smith Bader, author of Hayseeds, Moralizers, & Methodists.

Carry Nation used rocks and brickbats for her first attack on Kiowa, where she smashed three joints. But she soon was carrying an ax as her favorite tool of destruction. The Kansas Museum of History houses many items from her legacy, including a Crandall hammer meant for masons.

During her second assault in late 1900, she destroyed Wichita’s finest hotel bar, for which she was jailed for three weeks.

Her tactics drew national attention—both praise and condemnation—and she justified her destruction by saying the saloons were illegal and shouldn’t be operating in the first place. She also trademarked her name so its message would ring out.

“She presented a formidable obstacle to anyone attempting to stop her; her size (6 ft., 175 lb.) and her use of the hatchet to smash saloons became legendary,” the Columbia Encyclopedia (Sixth Edition) notes. “Nevertheless, she was often attacked and beaten badly and was arrested 30 times in her life. Because of her unorthodox tactics, most temperance organizations were hesitant to support her. She did, however, focus public attention on the cause of prohibition and helped create a public mood favorable to the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment. She was also a forceful advocate of woman suffrage, although she received little support from suffrage organizations.”

Her tongue was formidable, too. She’s famous for this blast: “Men are nicotine soaked, beer besmirched, whiskey greased, red-eyed devils.”

She didn’t confine her brand of political commentary to faceless groups. She suggested President William McKinley could have survived his assassination in 1901 “had his blood not been poisoned with nicotine.” And she dismissed the next president, Theodore Roosevelt, as a “bloodthirsty, reckless, cigarette-smoking rummy.” She labeled Los Angeles as the most “immoral” city she’d ever seen.

Her ax wielding only lasted a year. By 1901, she was on the lecture circuit, raising money to pay off the many fines she’d racked up from all those arrests. Besides her speaking fees, she found an amusing way to make more money—she sold pewter hatchet pins!

In 1903, she appeared in a play titled Hatchetation. By then, her husband had divorced her, claiming she’d abandoned her family for her cause.

She lived in Kansas until 1905, when she moved to Oklahoma Territory and helped that state enter the union with a dry constitution. She toured Europe in 1908, and by 1909, she had settled in Arkansas, where she died at age 65.

She never lived to see the 18th Amendment that imposed prohibition on the entire nation.

For the last 32 years, Carry Nation has been celebrated with a festival in Holly, Michigan. “The Carry Nation Festival is held each year to honor the great prohibition’s visit to Holly back in the days when Holly was a booming railroad town,” its website notes. “Holly was a perfect choice as it was riddled with taverns and ladies of ill repute. Those railroad workers were known for their sinful ways, and Carry was determined to clean up the town. Our festival commemorates her feisty visit to Holly.”

Holly may be the only town left that’s willing to pay public tribute to the ax-wielding prohibitionist.

“Carry Nation’s use of violence to accomplish her ends may be seen as part of frontier thinking, where each man thought he was a law unto himself. But by the early 1900s, such thinking was clearly out of place. Carry Nation has gone down in history almost as a joke, but her name is classic among women of the American West,” writes Judy Alter, in Extraordinary Women of the American West.

As usual, Carry A. Nation gets the last word. Her tombstone is inscribed, at her re-quest: “She Hath Done What She Could.”