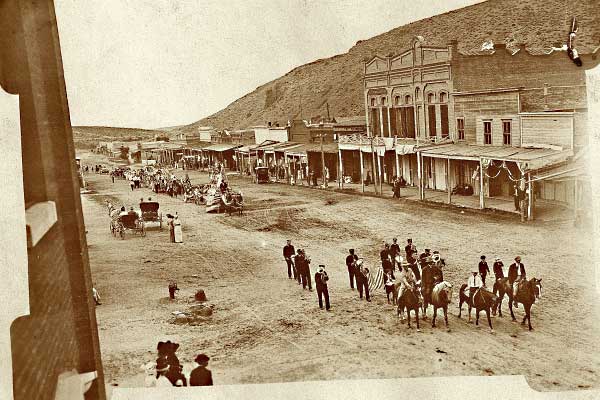

Imagine entering a town that, technically, no longer exists. Imagine the bustling town; the thousands of people whose hopes and dreams came to life in the now skeletal buildings and empty streets.

Imagine entering a town that, technically, no longer exists. Imagine the bustling town; the thousands of people whose hopes and dreams came to life in the now skeletal buildings and empty streets.

Imagine a hot and dry wind in your face as you open your car door and enter this eerie scene. The silence. The lifeless hard ground. Out of the corner of your eye, you see a lizard dart from the shade of a rock, then hear the lone cry of a hawk lazily circling above in the white hot sky.

Welcome to Rhyolite, Nevada: a true ghost town.

The town of Rhyolite—named for the volcanic rock and sand that covers the area—was born in August 1904 as the result of a gold strike made by prospectors Shorty Harris and Ed Cross. Several towns appeared due to this strike (known as the Bullfrog Strike), but Rhyolite grew to become the cosmopolitan city that surpassed them all. It is estimated that between 3,500 to 10,000 people lived in Rhyolite during the boom years between 1905 and 1912. By 1919, the prosperous gold vein dried up, and Rhyolite became a ghost town.

Back in her heyday, Rhyolite had three water systems, three train lines, a telephone and telegraph office, electricity wired all the way from Bishop Creek, California, over 50 mines, three newspapers, an opera house, a symphony, baseball teams, tennis courts, three swimming pools, two undertakers, three hospitals, eight physicians, two dentists, 19 lodging houses, 18 grocery stores, over 53 saloons (imagine that), a Catholic and Presbyterian church, and a very extensive red-light district. The Rhyolite Herald proclaimed to the world:

“Rhyolite is awakening! Are you a live one or a dead one? We have no room here for the man who won’t make a hustle for the good of his own town”.

The most famous ruin of Rhyolite is Tom Kelly’s Bottle House. Tom Kelly, a 76-year-old Australian, began the unique structure in September 1905 and completed it February 1906.

In 1905, the cost to ship building materials by wagon was very high, and the railroads had not yet arrived in Rhyolite, so Kelly built the house with what was available: bottles and mud. Most of the bottles were beer bottles, some wine, Sarsaparilla, mineral water, Worcestershire sauce, and medicine bottles. By the time Kelly finished the house, he used close to 30,000 bottles. Because water was expensive, Kelly did not bother washing the bottles before adding them to the structure, leaving behind the residue of 90-year- old beer, medicine, and wine, which is clearly visible. One of the bottles still houses the carcasses of 90-year-old crickets.

When Tom Kelly left Rhyolite, the next occupant of the Bottle House was Paramount Pictures. In 1925, the studio came to Rhyolite to film a movie, restored the Bottle House, and used it in their picture. They moved on, and the next occupant turned it into a museum and curio shop. Finally, in 1954, Tommy Thompson, his wife and grandson, arrived to take care of the town. They used the Bottle House as a curio shop and talked to the occasional tourist about its history. They lived there for 35 years and watched over the crippled town, keeping it preserved for future generations.

The end of Rhyolite occurred for two reasons: it was founded on speculation and there was never enough gold to satisfy its dreams. In 1907, after the San Francisco earthquake, a financial panic caused investors to lose interest, and they pulled out. By 1910, the streetlights were turned off, and the Porter Brothers General Store closed. Rhyolite’s population dropped down to 675. In 1911, the neighboring Montgomery-Shoshone mine closed. Rhyolite was completely deserted by 1924. The last known original Rhyolite resident was Betsy Moffet, who died at the age of 110, holding on to her hopes that the dying town would once again be revived.

As the years passed, people passed through Rhyolite to recycle its building materials. Houses were taken apart for lumber or moved to new towns. Miraculously, a few buildings, besides the Bottle House, have survived the ravages of time. The $90,000 three-story Cook Bank still looms over Rhyolite’s one paved road. The $20,000 concrete Rhyolite School, as well as the jail, the Porter Brothers General Store, the Las Vegas Tonopah Railroad Station, and various hearty foundations and walls, brave the desert winds and flash floods. At the main entrance of Rhyolite are modern-day sculptures, which strike an odd contrast to the antique ruins. In 1984, Albert Szukalski, a Belgium artist, created the Gold Well Open Air Museum. The sculptures include an eerie, life-size creation of the Last Supper, made with white sheets and fiberglass. There is an odd jumble of chrome car bumpers and a huge, rusted silhouette of a miner and a penguin. (According to legend, the sculpture is of Shorty Harris. When Shorty was drunk, he would wander through town pretending to have a penguin by his side.)

Today, Rhyolite is protected by the Bureau of Land Management, and closely guarded by rangers and volunteers like 80-year-old Clint Boehringer and his wife Ellen. The couple guards the Bottle House during the winter months, until another couple relieves them for the summer shift. One of their duties includes guarding the Bottle House from vandals and thieves. The Boehringers also make emergency repairs, and educate curious visitors about the historic site. One rule heavily emphasized upon a visit to Rhyolite is: look at it, photograph it, and leave it! To take any part of Rhyolite with you can result in a hefty $5,000 fine. Each of the 30,000 bottles making up the Bottle House is considered an artifact, thus thieves may think twice before claiming one.

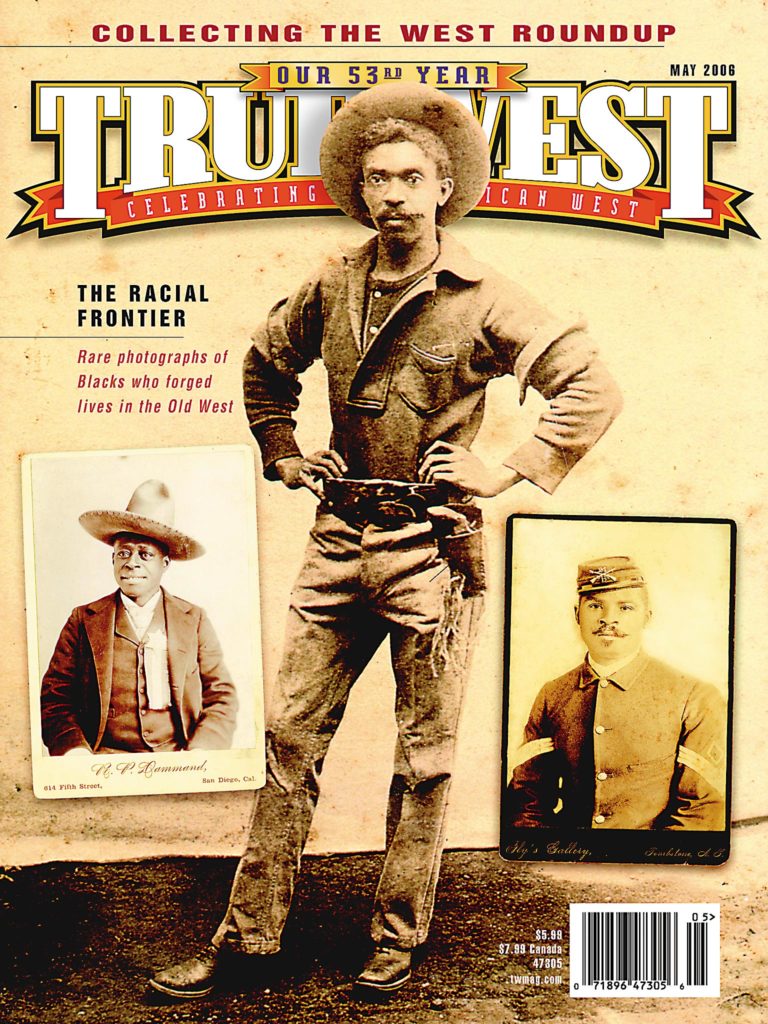

The West is famous for its ghost towns—towns that were built on a dream and quickly abandoned for better opportunities. We are lucky to experience Rhyolite, thanks to the people who recognize its valuable and fascinating history. Every year, approximately 70,000 visitors from around the world pass through Rhyolite with visions of Western folklore stirring their imagination. Imagine the West without ghost towns. It just wouldn’t be the same.

Robin Bronsky is a freelance writer and website designer in Freehold, New Jersey who’s fascinated with ghost towns. This is her first article for True West.