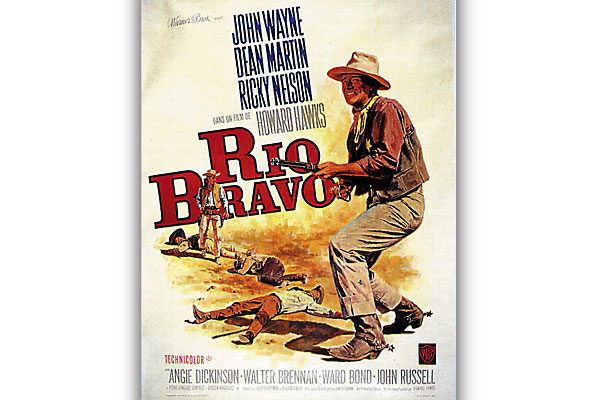

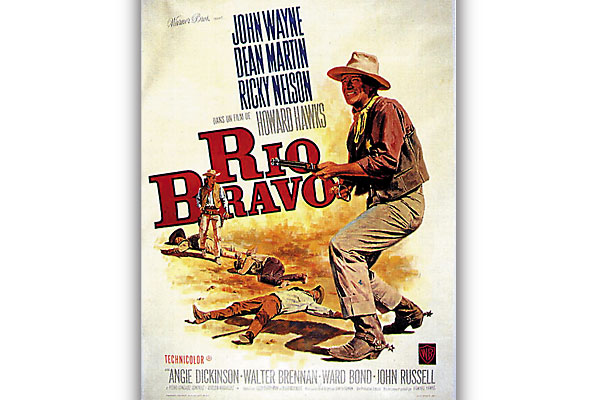

Some Westerns grow in stature, like The Searchers (1956), while others stay comfortably familiar, like The Magnificent Seven (1960). Some films resonate, others dissipate, but very few sit both inside and outside of era, genre and style like Howard Hawks’ Rio Bravo (1959).

Some Westerns grow in stature, like The Searchers (1956), while others stay comfortably familiar, like The Magnificent Seven (1960). Some films resonate, others dissipate, but very few sit both inside and outside of era, genre and style like Howard Hawks’ Rio Bravo (1959).

At first glance, the picture is a relatively modest good guys/bad guys standoff story starring John Wayne as the papa bear audiences knew and loved. But going a little deeper, it becomes clear that Rio Bravo is a movie that only gets more interesting with distance and age.

The new double disc DVD edition—with commentary by Peter Bogdanovich and Richard Schickel, and three extra documentary features—makes it clear that Rio Bravo represented a turning point for Wayne, Hawks and the American Western.

Hawks had only recently returned to the states from a lengthy layoff in Europe after his last picture, Land of the Pharaohs (1955), deservedly tanked. Several subsequent projects had failed to launch and, after 30-plus years of brilliant filmmaking, Hawks was looking for a road back in. He couldn’t fail to notice that during his absence the TV Western had not only grown up, but it had also become the most popular form of entertainment on the black-and-white tube. Hawks decided to make a Western.

Prior to Rio Bravo, Hawks’ only Western had been Red River, starring Wayne in one of his most important performances as the brutal trail driver Tom Dunson. Opposite Wayne was the young, method-trained Montgomery Clift as his surrogate son, Matthew Garth, and Walter Brennan as Nadine Groot, the mother hen. The Western was about a family of men, and Wayne’s work in the picture was so strong that, according to legend, it caused John Ford to call Hawks and declare “I didn’t know the big sonofabitch could act!”

So it doesn’t come as a surprise that Wayne was willing to jump into Hawks’ new picture, especially since he hadn’t made a Western since The Searchers, three years earlier.

But while there are some similarities between Red River and Rio Bravo, Hawks was looking at Westerns, and moviemaking, in a simpler way. His new picture meant gathering all of his themes and ideas, tics and tricks, into a single streamlined story.

In this case, the theme comes from Hawks’ dislike of High Noon and 3:10 to Yuma, movies about men who were cut off from help in desperate situations. Hawks often said that his idea was to create a picture with similar tension, but to have his central character (Wayne) refuse all offers of help from “well-meaning amateurs” who had lives and families to consider. Illustrating his point, the one friend who tries to help Wayne in the film, played by Ward Bond, is murdered in the street.

It’s a good story, but closer to the truth is Hawks’ desire to shoot a number of prolonged scenes in closed sets, underscoring the drama of men who bond in a tough situation, “but with a little sex,” as the Preston Sturges line goes.

As Sheriff John T. Chance of Presidio County, Texas, Wayne is painted with such broad and familiar strokes that he seems like a Warholized version of himself. Garry Wills, who wrote John Wayne’s America, states that Rio Bravo was a stylistic “dead end” for Wayne, but it was more of a summation. Even his costume is a collection of items from his past, including his Stagecoach hat and the Red River belt buckle Hawks gave him.

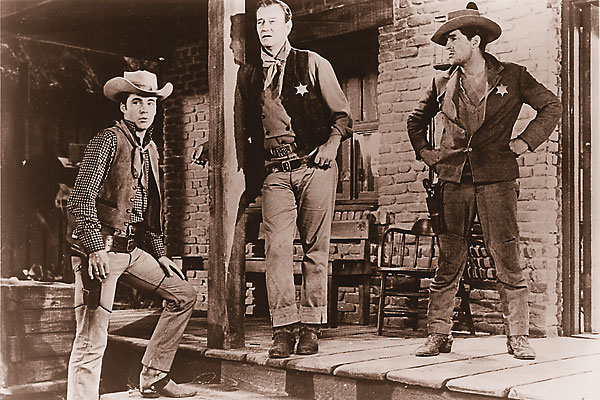

Besides Wayne, the rest of the cast are as much caricatures as characters.

Dean Martin, the second banana, plays a drunken, bedraggled, disgraced deputy named Dude, who, we learn, croons pretty good once he’s crawled past a major case of detox jitters and regained his honor and the approval of the towering Wayne. Martin had done some challenging dramatic parts just prior to Rio Bravo, but he still had to fight for the part by flying in overnight from a gig in Vegas to audition and put on a costume that Hawks eventually blessed.

Walter Brennan plays Stumpy, pretty much the same gabby, gummy geezer he’d played for Hawks in Red River and To Have and Have Not (1944). The two had a history dating back to his role as “Old Atrocity” in Hawks’ Barbary Coast (1935), a part he sealed when he asked if the director wanted him to play the part with his teeth in or out. (Out, apparently, was the answer.)

At the time, Brennan was doing well on TV as Grandpa McCoy in the original hillbilly sitcom, The Real McCoys, which ran six seasons from 1957-63. The story that Hawks always told was that he wanted Brennan to leave Grandpa off the Rio Bravo set, but the truth is there’s a lot of Amos McCoy in Stumpy, which is what audiences wanted to see. The biggest difference between the characters is that the TV Brennan wore teeth and smiled a little more.

Ricky Nelson was still going strong at that time as a pop-rockabilly TV idol, middle America’s Elvis-con-leche. Nelson’s single, “Never Be Anyone Else But You,” had just skirted the top of the charts when Rio Bravo opened in spring 1959. The summer before, his “Poor Little Fool” had hit number one.

Hawks, who always had a shrewd instinct for the demographic bottom line, hired him to play Colorado, a dreamy-eyed, singing gunslinger. Once he was aboard, Nelson was handed the same playbook of affected mannerisms that worked so well for Clift in Red River, in particular the ever-popular one-fingered nose rub that indicated thinking. Clift was better at it, but Nelson was okay, considering.

The only unfamiliar cast member was relative newcomer Angie Dickinson. The part she played, as a fugitive card sharp named “Feathers,” was a reconstituted version of Lauren Bacall’s character “Slim” in To Have and Have Not, a fact that Dickinson discovered years later when she was watching the Bogart-Bacall movie and saw her dialogue coming out of Bacall’s mouth. Not surprising, considering that Slim and Feathers were both created by the same screenwriter, Jules Furthman, who knew exactly what Hawks required in his handsome, lanky dames.

Which is to say that film is endlessly self-referential. Even the Dean Martin/Ricky Nelson musical number, “My Rifle, Pony and Me,” was lifted from part of Dimitri Tiomkin’s earlier score for Red River. Playing connect-the-dots is a full time job with Rio Bravo, but it’s all part of the movie’s charm, and being outside of the joke does not in any way diminish the enjoyment of the picture.

American critics were not warmed by the film when it premiered, perhaps because it all seemed so familiar at the time. Even today, the picture stirs feelings both pro and con. Paul Simpson, in his recently published The Rough Guide To Westerns, refers to it as the “Most Overrated Western,” largely due to its languid pacing and length (141 minutes).

The question is, how long can John T, Dude, Colorado, Feathers and Stumpy hold a valuable prisoner in the tiny jail while a passel of hired guns are just up the street hoping to send them to boot hill. Dude has the shakes, John T. Chance is worried about his deputy and unnerved by the advances of the sexy Feathers, Colorado has a song in his heart and an itchy nose, and Stumpy is, well, Stumpy. You can’t tell a story like this without giving it some room, and time, to breathe. Rio Bravo should be savored, like a fine wine.

Rio Bravo is as much a meditation as it is a movie. Hawks did something audacious with this film—he swallowed his trepidation and threw together everything he had into a step forward. It just so happened that he had the talent and the chops to make a simple Western into something both familiar and deceptively different.

In a landscape littered with no-budget, half-hour TV Westerns that popped like strings of firecrackers because they rarely had the time to develop characters, Hawks made a movie with a long, slow fuse that is entirely character-based. All the same, there are some serious fireworks in Rio Bravo, and they’re worth the wait.

Angie

TW: Rio Bravo was a real breakthrough role for you, and then you were in Oceans 11. When did you begin to feel as though you’d hit the big time?

AD: I knew that I got a tremendous break in Rio Bravo. I still didn’t feel like a star, but I felt that I certainly belonged in the movie. I don’t think I felt like a star until Police Woman.

It really starts with Feathers, though, doesn’t it?

You know, Dean Martin would only call me Feathers—he never called me Angie [laughs].

Hawks’ women had so much in common with each other.

Yeah, exactly. We had the same lines.

Many people, I’m certain, feel that of all of the women, you hold up the best.

I think so, because even though we probably had the same lines, I watched [Red River], I loved it, but I don’t remember Joanne Dru other than I know she’s in it. So, I hope what you’re saying is true. Of course, video helps [laughs]—Rio Bravo is on so much, you just can’t help but remember me.

The clothes that Feathers wore don’t exactly hurt.

Yeah, they were nice [laughs]. They were great.

Would that you might have kept your wardrobe.

Well it wouldn’t fit today. Hawks was very involved in it—he didn’t want the stiff costumes that most Westerns had. He wanted them soft, and he was sooo right. I had soft skirts. I didn’t have that stiff petticoat underneath. He had a big hand in choosing the wardrobe.

Seems as though Hawks was hands-on in most aspects of his productions.

Well, I was not privy to all of it, but certainly to mine. He was right there, and he was so correct, and that’s another reason [Feathers] was very special. She was the feminist of her day.

Self sufficient, a card sharp, but in the presence of John T. Chance, she begins to gush a bit.

Because her femininity comes out.

Were you ever intimidated by Wayne, or just acting as if you were?

Oh no, I was totally intimidated. No, no. It was very daunting to go up against Wayne, with Hawks, as early in my career as I did. I was not really ready for it.

It seemed to come naturally.

Well, thank you. It worked, but I was really in over my head, and Hawks was very good. He just stuck with me and didn’t give up. And it worked. But those were very tough scenes to do.

A lot of tumbling dialogue.

You had to with Hawks. Ever see His Girl Friday? She [Rosalind Russell] never stopped talking. She’s the role model.

Nobody ever stops talking in Hawks’ His Girl Friday.

But she is a non-stopper. She’s the epitome of the Hawks woman that never stops talking. And Katherine Hepburn, in Bringing Up Baby, is just about as bad, but not like Rosalind Russell—she really poured it on.

Well, Rio Bravo is a bit of a screwball comedy.

Well, yeah! Especially in the way they tease Duke and all, but not as screwball compared to the other ones. But Hawks made great comedies. But you’re right—whereas Red River had very little comedy in it, Rio Bravo was all comedy. You hear the constant cackling of Walter Brennan and the teasing and stuck in the jail and—-it was just glorious.

Then there’s the “flower pot through the window” scene.

I had to aim very carefully. It was a very, very difficult scene—a funny scene. Again, great expectations from the director to do something good. It was not just throwing a flower pot. He had a way of wanting you to do something very special. Yet he would not tell you how to make it special. He wanted you to come up with it by yourself. And therefore, it would be special. If he told you, it wouldn’t be special. So the combat—I’m not sure that’s the right verb—between Hawks and your actor was very interesting. He wouldn’t tell you very much; he would just leak out a little of what he wanted, and you had to play with it.

I think the fact that he had a fun set is key to what makes a Hawks movie fun.

Yeah, but they’re not mimicking him like Woody Allen. The worst Woody Allen movies are the ones where everyone talks like he does.

Particularly Michael Caine.

Particularly Kenneth Branagh. And you can’t help it ’cause it’s so appealing and so funny and delicious. And it’s very hard not to sound like him when you’re acting what he wrote, but that’s what Hawks did not want; he didn’t want us all to look like Hawks, or look like each other. Each one was an individual because he wouldn’t tell you what to do, he would just hint and let you take it from there. And that’s why it worked.

I expect when someone like Hawks gives you his confidence, makes you feel you can handle it, you can.

Hopefully.

It seems to have worked for you.

I said to him, “You know, I was always told if I could ever work for George Cukor or Howard Hawks I would really be set.” And he said, “Well, you know why they say that—we do all your thinking for you.” [Laughs] I was so thrilled that I finally got to work with the great Howard Hawks, my first enormous job. And to be chosen over all those other women. So he knew you were considered lucky to be in one of his movies, to say the least. He was wonderful. Those were special times, and I was lucky to be there.