Karl May was a man of many parts, to say the least. Part Zane Grey, part P.T. Barnum, part Soapy Smith, part Walter Mitty, part Nietzsche, part Billy Graham and just maybe part madman.

Karl May was a man of many parts, to say the least. Part Zane Grey, part P.T. Barnum, part Soapy Smith, part Walter Mitty, part Nietzsche, part Billy Graham and just maybe part madman.

He became Germany’s best-known, best-loved and most-read author. His fans included Albert Schweitzer, Albert Einstein and Adolf Hitler.

May (pronounced “my”) lived a life just as fanciful as the Old West novels he wrote. He was born in Saxony in 1842, the fifth of 14 children of poverty-stricken weavers. May made a go of being a teacher, but that didn’t afford him the lifestyle he wanted. He ended up in jail in 1865—either for petty theft or a series of con jobs on tailors (maybe something Freudian going on there?).

His prison stint had one benefit: he oversaw the institution’s library. Yet not until his release after a second prison term, from 1870-74, did May put his reading to good use. He wrote magazine and newspaper articles, and became an editor for small publishing houses. He quickly found a successful formula—writing adventure stories set in foreign lands like the Middle East, Africa and frontier America. His tales featured near-Superman heroes with a strong sense of Christian morality.

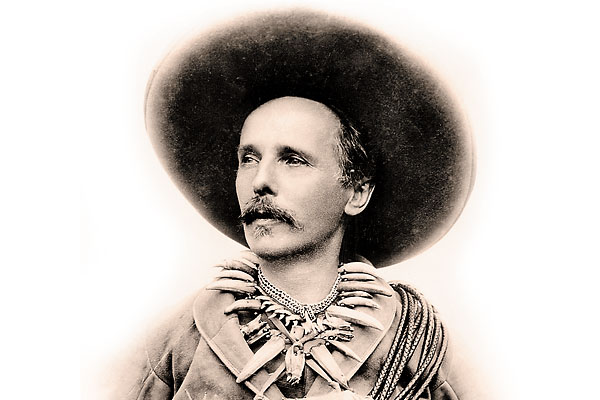

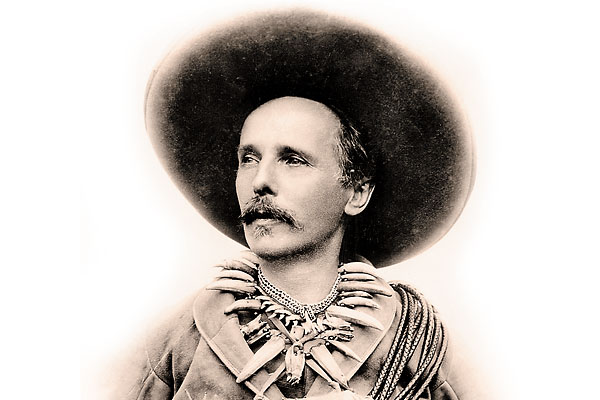

This is where the May imagination came to the fore. May had never visited any of those places (he would visit the U.S. in 1908, but went only as far west as Buffalo, New York). Further confusing the facts, May would boast he was the hero featured in his stories. He even hired a photographer to capture him wearing the “authentic” clothing described in his stories.

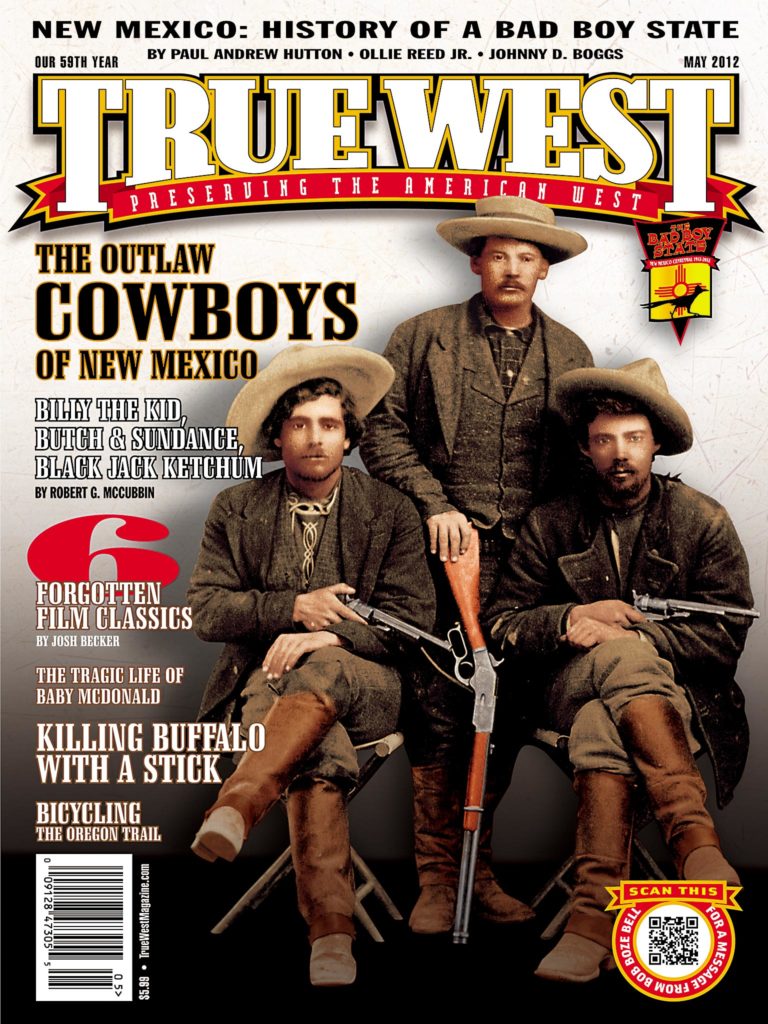

He hit the big time in 1893. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West came through Germany at the same time May was publishing his first Winnetou books. The Buffalo Bill craze spurred huge sales for May’s tales, not just in Germany, but also throughout Europe.

May’s Winnetou was an Apache chief who becomes the blood brother of the hunter/scout Old Shatterhand, the Superman-type German-American hero who is a deadly shot and a Christian gentleman. They have a series of adventures through three books published in 1893, and another in 1909.

Even when, in 1900, fans found out May had never visited the U.S., let alone been a frontiersman, they remained fascinated by his American West. A giant success, May bought a home he called Villa Shatterhand in what became East Germany. As a highly-sought speaker, May drew thousands to his last speech, in 1912, the year he died. One then-unknown member of the audience was later to loom large: Adolf Hitler.

Hitler called May his favorite writer, admitting his books had “overwhelmed” him as a child. He took to heart the Shatterhand hero and wanted his followers to be similar Supermen, full of courage and nobility, but unbelievable fighters when the circumstances called for it. (During WWII, he even asked his generals to read May’s books.) Some believe Hitler discovered the symbol he would co-opt for the Nazi Party—the swastika—from May’s stories. What Hitler conveniently ignored from these tales was the humanity, the Christian themes and May’s empathy for people of color.

May’s legacy managed to survive all that (as well as a Cold War ban in East Germany). Roughly more than 200 million copies of his books have been printed, in nearly 40 languages. Movie adaptations started in the 1920s, ending with a series of “Sauerkraut” Westerns starring Lex Barker as Old Shatterhand in the 1960s. A new adaptation is in the works, scripted by Dances With Wolves author Michael Blake.

This year, Germany will host an untold numbers of events tied to the centennial of May’s death—with the epicenter at the museum housed in his Villa Shatterhand, in the town of Radebeul.

May would probably consider these tributes a dream come true.