The American West at the close of the 19th century was a land of contradiction.

The American West at the close of the 19th century was a land of contradiction.

Progress-minded business men, pioneers intent on building a home, railroad magnates with dreams of empires and those who gradually saw their freedoms disappear through greed and lawlessness.

Such was the fate of the young Chinese women sold as servants by mainland Chinese families and sent to serve as prostitutes in the towns and camps of the American Midwest. Theirs was a fate worse than death.

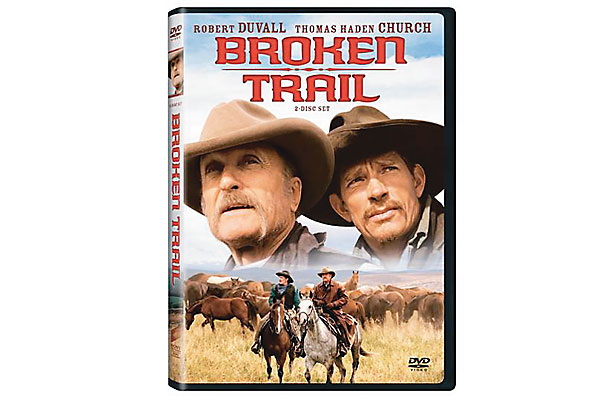

Writer Alan Geoffrion, Producers Stanley M. Brooks, Rob Carliner and Robert Duvall, and Director Walter Hill (Wild Bill) have woven a magnificent tapestry filmed in the rolling hills near Calgary, Alberta, in Canada. Duvall headlines a cast that includes Thomas Haden Church, Valerie Tian, Chris Mulkey, Scott Cooper, Jadyn Wong, Olivia Cheng, Gwendoline Yeo and Caroline Chan.

Broken Trail, a miniseries which airs on June 25 and 26 at 8:00 p.m. on AMC, follows veteran cowboy Print Ritter (Duvall) and his nephew Tom Harte (Church) as they undertake a dangerous 1,000-mile journey from Eastern Oregon to Sheridan, Wyoming, in 1897. Along the way, they encounter a corrupt slave trafficker taking five Chinese girls to a mining camp to be the camp prostitutes. Rescuing the young women, the men put themselves and their livestock at risk during their escape. Faced with dangerous circumstances, Ritter, Harte and the women discover their strength as they overcome cultural barriers.

What’s the message behind Broken Trail? True West conducted a roundtable discussion with actors Robert Duvall and Olivia Cheng and writer Alan Geoffrion to find out.

TW: Let’s start off with how Broken Trail came to be.

AG: We are both friends and neighbors. We are lucky that way.

RD: For a long time now.

AG: Well, Bobby’s got a place down in Argentina, a ranch. He was getting ready to go down for Christmas holidays, the year before last, and we were getting together for lunch. I told him about a story that had been told by me by an old rancher.

I don’t know if you’re familiar with the Haythorn Land and Cattle Company in Ogallala, Nebraska. It’s a pretty big outfit. The head of it, at that time, was Waldo Haythorn. His son Greg runs it now. Waldo told me about his grandfather taking a herd of horses from Eastern Oregon back to the Rosebud Reservation for a government contract. We were just talking, not shop. At some point, he said, you should write that down. That’s a pretty good idea. So, the next morning, I got a call at 8:30, and he asked me how much I’d written. So, I thought I’d better get started. In about five or six weeks, I had the basic framework laid out.

Another thing that I’d been fascinated with and wanted to intertwine the two. There was a lady in San Francisco in the late 1800s, early 1900s, named Donaldina Cameron [see June 2004, Women of the West]. She ran a rescue mission in San Francisco for young Chinese girls to try and save them from being sold into prostitution. A lot of these girls ended up in cow camps and mining towns around the West. Because they were so cheap to bring over and the control [over their lives] was so complete, they had a brief, violent life in North America. Their average life in the country was five years before they succumbed to either suicide, violence or disease.

So I started working on the idea; I had the thing laid out. From then on, I’d call up [Duvall] or we’d get together for lunch. The first version was set up for a movie in about six months as screenplay.

RD: From a story viewpoint, the thing that came first was the journey on the trail, then the women and their plight came after that. Geoffrion did a lot of research on the plight of these women and made it as factual as possible. It makes a very compelling story that needs two nights to tell it.

TW: How much input did you have in the film Mr. Duvall?

RD: [Alan] and I conferred on this script from its genesis. As Alan said, it started at a lunch and over time, we both shaped it.

TW: Did anyone else help with the script?

AG: I had great people like Horton Foote, the great screenplay writer (To Kill A Mockingbird, Tender Mercies) to vet [the script] and give me some good advice. The other thing, I had a lot of cowboys read it—guys earning their paycheck up on a saddle.

TW: Is it a true story?

AG: People have asked me if this is a true story. This is a collection of true stories. I did not have to use my creative imagination for the original script. Everything that happened in that draft was either from a private diary, correspondence and letters. Real events. Real people. We wanted to get closer to the truth and show the Western experience through the eyes of different people.

TW: Olivia, as a young Asian actress, how did the role of Yee Fung change your perception of Chinese history in the U.S.?

OC: I was not aware of the forced slavery before I got the role, and even a little embarrassed when I found out. It forced me to research the story. I had not known that even in the early 1800s, young Chinese girls were brought over to America and forced into prostitution in brothels and mining camps across the Midwest. It is an issue that still exists today, and after my research, it blew me away. Thousands of girls, possibly hundreds of thousands, were brought over here after being sold by their families without their say. Many took their own lives, died in “hospitals” (out of sight or out of mind) or were killed by the brutality of the camps. It was shocking … young Asians are not educated about this. During filming, I realized that if I was born in a different time and different place, it could have been me.

TW: With the role of the Chinese girls so central to the film, how did you go about characterizing the women?

OC: When I first heard about the project, I was wary. Here we go, another Hollywood project where the Asian characters are reduced to one dimensional human beings and not given the chance to show that they are damaged people. I did not want to be a living prop. When I realized that we were essential to the story and we could be normal “little” girls, I wanted to play Yee Fung with dignity. I wanted her to be a human being. The tone of the movie let me know I could do that.

AG: There was an incredible amount of people who took part in the Western experience. The classic Western has zeroed in on the tall, silent, Anglo cowboy who could do no wrong. The real backbone of the story of the West are the women, and [the story of these Chinese women] had not been told before. We wanted to do that.

TW: Cast-wise, Broken Trail is rich. Duvall, Thomas Haden Church, Gwendoline Yeo, Valerie Tian, Scott Cooper and you, Olivia Cheng, add so much to the finished product. How difficult was casting for Broken Trail?

OC: As for Thomas Church, Tom is so known for his comedic roles. George of the Jungle. Sideways. A lot of people will realize there is more to him than the roles he portrays so well because he is such a good actor. When I met him on set, I expected him to be the life of the party, but he wasn’t. He is a serious, articulate, intelligent guy.

[His character] Tom Harte is a cowboy with issues. Really hard up. First time we meet him, he’s castrating cattle, not climbing the cowboy corporate ladder. This cattle drive for him represents a second chance at a better life … as the story unfolds, you learn what shapes him into the cowboy he is. He is the last person you would expect to show compassion to the girls. He takes them under his wings but [is] not very affectionate. Duvall is the more affectionate one. Kind of like the father. Tom Harte is not warm and bubbly. Underneath all the bitterness, he is a good man.

AG: The girls were a different matter.

RD: Olivia came from Edmonton. I was the one who found her on the tape out of about 135 actors across Canada, which I saw in one afternoon, and she stood out in a good way. And I figured, why not let Edmonton be represented, since we had good actors from other parts of Canada. My own sense of a quota system.

OC: As an actress, it was like winning the lottery. To get to watch one of the Living Legends is an amazing experience—a lightning strike. It changed my perspective on acting. Robert Duvall brings something different to every take. He doesn’t have a set reaction. He reacts, not acts. He plays off what the other actor brings. He taught all of us that acting is about being on camera and letting it capture what you are doing. Gwendoline Yeo was the most experienced. Jadyn Wong, Valerie Tian, Caroline Chan and I were very green.

TW: Isn’t that mixture of experience and inexperience what Alan wanted to capture in the film?

OC: Yeah. Alan told us that was one thing he couldn’t put into the script, was our natural connectiveness and chemistry. We bonded as a unit and became one. It was what they wanted. We became close to each other. When we were scared, we put our arms around each other. That’s what I remember. We all brought something different to the film.

AG: The girls were always going to be the secret weapon. When they come up on screen, you go WOW. I wanted to make sure they weren’t relegated to some stereo-typical background characters. They seemed to like it. I told them, “I’m not a woman, nor am I Chinese. I try to keep the emotions in a gender neutral place. If you find something that is not quite right, come talk to me.” And they did.

OC: Alan told us “I am an old white guy, if you have a problem with a scene, let me know.” He appreciated our input. He doesn’t know our Chinese culture or even the female mind. One example of the collaborative effort is when Print Ritter, the Duvall character, is trying to make first contact with the girls so they know he is a friend. Duvall can’t understand them, so he numbers them off. One, Two, Three, Four. As the girls talk, they realize what he is doing. “He’s numbering us. You’re number one, two, three, four.” I told Alan that phonetically, the word four sounds like death. Fh instead of Th makes a difference. We added a little scene to explain that. “I don’t want number four. I don’t want to die,” we had the girl say. The Asian audiences will understand; our superstition is very strong.

TW: The production crew for the film is very talented. Director Walter Hill, Robert Duvall and yourself.

AG: The Canadian crew was fantastic. They did a great job. I worked up there in 2002 on Open Range, and it was the same experience. For that one, we had double the budget for a two-hour [film] as opposed to half the budget for a four-hour [miniseries]. Great people. Ken Rempel, the production designer, would wave his magic wand and something would happen. I was amazed at how many of the crew, the grips, the cameramen, the guy who drove the honey wagon would come up to me and say “I read the script.” They took a real interest in it. The great Alberta scenery is second to none. The Bews family [ranch hands in the miniseries] is just amazing to work with.

OC: Walter Hill was very much a “roll the camera” type director. I can count on my hand the number of times he stepped in and asked us to change something.

AG: With Walter at the helm, he wanted more action. We had thought of it as more of a character-driven film. We understood and put some action into it, beefed up the villains a little, and both Bobby and I were very clear that we did not want to have this like all the other Westerns.

TW: Was the film originally slated to air on AMC?

RD: It was a go project at CBS, but we turned them down because of certain things we asked for. Shortly thereafter, AMC came aboard. We had written the film as a feature length, but they wanted to do a two-night miniseries.

AG: AMC wanted to do a two-night miniseries, so it doubled the length of shooting time and scripting time, but we felt like we had a lot there. Westerns tend to run a little longer than action films like The French Connection; it’s just a different cadence. And there was no shortage of subplots.

TW: With the film coming up for broadcast, has the work stopped?

AG: That’s ironic you would ask that. I still get e-mails asking for input, and this morning, I received one. They’re still putting the finishing touches on [the film]. Right now, I’m working on the novel, which will be published by Fulcrum Press of Colorado, and after that, Bobby and I have a couple other potential projects.

RD: We’re still editing the film. In terms of handling the roles of actor and executive producer—as an actor, it was fine, but the other juggling process was a nightmare.

TW: What’s next?

AG: The novel.

RD: After broadcast, some rest and a badly needed vacation in Argentina.

TW: Any final thoughts on the film?

OC: For a first major role, it is an amazing film to be in.

AG: Bobby had said he really wanted this to be the third jewel in the crown for him, Lonesome Dove, Open Range and now Broken Trail.

RD: It was not an easy experience by any stretch of the imagination, but it was very worthwhile and fulfilling for me. I feel when this movie airs, it will be very good timing for the United States of America.

Tim Lasiuta is a Canadian-based writer with varied interests. Visit www.LoneRangerCartoonist.com to find out more about his latest book.

Photo Gallery

– All photos by Chris Large / AMC unless otherwise noted –