So little information exists about the childhood and youth of Billy the Kid that many of us, happening upon the merest morsel, swallow it eagerly and entire.

So little information exists about the childhood and youth of Billy the Kid that many of us, happening upon the merest morsel, swallow it eagerly and entire.

So for the best part of 50 years, El Paso journalist Bill McGaw’s account of Billy’s schooldays has been widely accepted as accurate. Based on a series of 1960 interviews with Patience Glennon, daughter of Mary Richards, the Kid’s schoolteacher in Silver City, New Mexico, the articles first appeared in the El Paso Herald-Post in 1960 and then in a short-lived magazine called The Southwesterner in 1967 (all in more or less the same form) and again in a little book called Southwest Sage that rarely finds it way into bibliographies. And what a dramatic tale they told!

The Richards family, McGaw wrote, emigrated to America from England in 1857. The crew of the ship they were on mutinied and killed the captain; Mary’s father, Dr. John Richards, took command of the ship, and got it to Galveston, Texas. Soon after this he, his wife Mary and the three children, Reuben, Mary and Edward, settled in Brownsville, where, within a year, the doctor was killed by Indians and his wife succumbed to yellow fever. A family friend, Lord Salisbury, had Mary made a ward of the British government and brought back to England where she was placed in the care of Dr. Bailey, regent of St. Aden’s College in South Hampton. Under his tutelage, she became a scholar and linguist. After spending a year each in Germany, France and Spain, Mary became a translator and secretary to Benjamin Disraeli, the Prime Minister of Britain. She was also selected as literary translator for Alfred, Lord Tennyson and art critic and writer John Ruskin, with both of whom she enjoyed a lifelong friendship and correspondence.

Dispelling the Legend

It’s a great story, but it turns out McGaw got most of it wrong. Mary Phillippa Richards was born in Southampton, England, on April 3, 1846. Her parents had married after a whirlwind romance; John Richards, 18, the son of a tavern keeper, was a lowly servant when he married Mary Ann Davies Quarrill in Christ Church in the parish of Marylebone, London, on February 23, 1842. The marriage certificate notes that the bride was under the age of consent (16) and that both bride and groom were residing at the same Southampton Row address, which might account for the opposition to the match apparently raised by Mary Ann’s brother Richard and her stepmother, who lived in stylish Mayfair and claimed direct descent from the English poet Francis Quarles (1592-1644).

When their first child, Reuben William Archer Darley Richards, was born on December 19, 1844, John and Mary Ann were living at a London coffeehouse; John gave his occupation as “commercial traveller.” It would appear he was a restless, ambitious young man, for only 16 months later when Mary was born he described himself as “independent,” inferring independent means. By the time a third child, Edward, was born on April 12, 1848, John Richards had become the owner of the coffeehouse.

In the fall of 1849, the family left Liverpool for New Orleans on the ship Sea King, with John Gray as its captain. They arrived safely on October 19; the nearest they had come to a mutiny was a fire on board, successfully extinguished. They settled in Brownsville. In the 1850 census, however, John is shown not as a doctor but a teacher; his letters home at this time speak of his starting a school.

On November 13, 1851, another child, Isabella Louisa Demas Lopez Richards, was born; her godparents were Matamoros-based Mexican consul Demas de Torres and his mother-in-law Brijitta Villegas de Lopez. Exactly one year later to the day, Mary Ann Richards died following an accidental fall. John begged his parents to come out and take care of his children, but it appears they were unable to do so. Soon thereafter, Isabella was adopted by her godfather and his wife.

Sometime in 1859, John was murdered by persons unknown in San Fernando de Preces, 75 miles from Matamoros. After his death, Mary was placed in a convent until arrangements could be made to send her back to England; her brothers lived with mulatto farmer James Primm and his wife. (The Primm family was a remarkable one: They had extensive land holdings in Fayette County, Texas, around a settlement—later Kirtley, now nonexistent—named for patriarch Dr. William Primm of Louisiana who sired a number of children by his black freedwoman. After his death in 1865, his son James became executor and manager of the plantation, which consisted of some 8,000 acres in Fayette and an additional 5,000 in Matagorda, Bexar and Live Oak Counties.)

Reuben went off to war; Edward, too young to fight, stayed in Primm. In 1862, Mary Phillippa returned to England. How or even whether the future Lord Salisbury might have been involved is unknown, but the man chosen as her guardian was not “Dr. Bailey from South Hampton,” but Dr. Joseph Baylee, philanthropist, polymath and principal of St Aidan’s Theological College in Birkenhead, near Liverpool. Born 1808 in Ireland and educated at Trinity College in Dublin, Baylee founded St. Aidan’s in 1846 and remained its principal until 1871, when he retired to the vicarage of Sheepscombe, a small village in Gloucestershire.

It seems unlikely Mary was educated at St. Aidan’s (where she might have proved something of a distraction—the college’s main purpose was to educate young men for the priesthood!). More probably she received her initial education from the brilliant Baylee himself—he spoke 19 languages—and later at an establishment called Miss Harwood’s Select School for Young Ladies in London. In 1869, she went to Mannheim, Germany, as a teacher/governess and became fluent in German. Later, as the companion of Edith Kennedy, a daughter of a socially prominent Dublin family, she was presented to Edward, Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII), at the court of Queen Victoria. While in the employ of the Kennedys, she met the critic Ruskin and (perhaps) Prime Minister Disraeli. Alfred, Lord Tennyson and British premier William Ewart Gladstone were close friends of Dr. Baylee and frequently visited his home. How well Mary may have known them is uncertain; there is not one mention of her in any of the extensive historical collections relating to them.

Mary’s Return to the States

Back now to McGaw’s newspaper story: In or around 1873, Mary returned to the U.S. to look for her brothers. In Ojinaga, Mexico, she learned that only a few years earlier, an English adventurer (her brother Reuben) had kidnapped the daughter of Don Felix Hernandez, married her and gone to live near Fort Stockton in Texas. When Mary finally located him in 1873, he was in Ysleta (El Paso), where he had a large cattle ranch and a family of four daughters and four sons. Reuben, in turn, informed her that their brother Edward was a rancher in Matamoros. Through relatives in Silver City, New Mexico, Reuben learned of a vacancy for a teacher there; Mary applied for, and was offered, the job, arriving there in 1873. Reuben turned his hand to freighting, passing on to several generations a freight line operating until the 1960s.

Once again, the facts are somewhat different. Mary was still in Dublin in 1873; she left the employ of the Kennedy family shortly after the tragic death of Edith Kennedy from cholera that year. And there was no reason for her to go to Ojinaga; it appears she knew exactly where her brothers resided. Reuben was living neither in Fort Stockton or El Paso but in Pecos County, where his “splendid ranch” was in fact a farm with a couple of horses and cows; his “extensive family” consisted of three children, his wife Francisca and her brother Joseph. Neither then or later did Reuben operate a freighting business; in fact, due to complications arising out of his Civil War service and severe mental deterioration, he died a relatively poor man. The “splendid ranch” was undoubtedly the plantation in Primm, Texas, where the other brother Edward was still living and working. In 1871, he married a local girl, Margaret Keller, and they had a son, John.

A memoir left by one of Mary’s daughters suggests Mary returned to America because she had become obsessed with the idea of educating her brothers’ children. In fact, she stayed in Texas only briefly.

New Life in Silver City

In the summer of 1874, Mary was appointed teacher to the children of Silver City. The one-room public school opened on Monday, September 14, 1874, but it is unlikely Henry Antrim or his brother Joe attended school during that first week, because just two days after classes commenced, their mother, Catherine Antrim, had died.

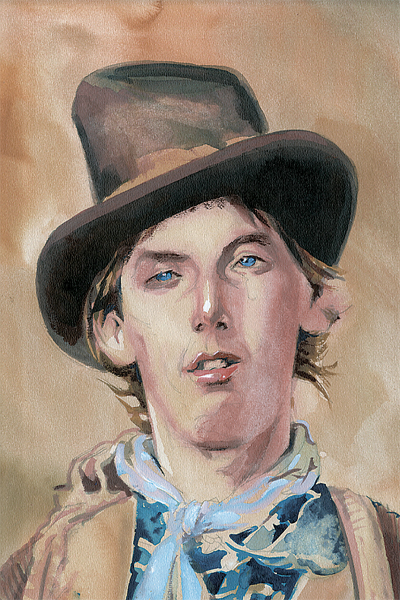

The funeral service was held on September 17, at the family home—a modest cabin at the corner of Main and Broadway. Arrangements had been made for the boys to stay at the home of Richard and Mary Hudson. When they resumed attendance at school, Henry soon struck up a good relationship with the new teacher. Many years later, she would remember him as a “scrawny little fellow with delicate hands and an artistic nature” who was “always willing to help with the chores around the school-house,” and certainly “no more of a problem in school than any other boy growing up in a mining camp.”

There were 29 children in Henry’s class, among them Louis Abraham, Charley Stevens, Anthony Conner and Harry Whitehill. Little Emma Whitehill, too young to be enrolled, attended anyway and sat braiding and unbraiding the fringe of the tablecloth on the teacher’s desk. Louis Abraham lovingly fashioned a paddle for Miss Richards to punish naughty boys, only to become the first naughty boy to be paddled with it. A monitor was appointed to fill the water bucket twice a day; pupils and teacher used the same dipper. Another monitor carried in wood and another kept the fire going in the open fireplace. There were no desks—just tables and chairs—nor was there a blackboard, but there were slates with slate pencils and a few books, all highly prized by the children. Miss Richards “had their interest excited and their advancement was certain,” reported the editor of the Silver City Mining Life on September 26.

In the aftermath of his mother’s tragic death, perhaps it is not surprising Henry, now 14, wishfully began believing he and Mary must be related. “He thought this because they were both ambidextrous,” Patience Glennon told McGaw. “My mother could write equally well with either hand, and so could Billy. He noticed this and he used to say he was sure they were related because she was the only other person he had ever seen, who could do things equally well with either hand.”

That fall, Henry appeared with the other kids in a minstrel show to raise money for the school. In mid-December, Mary Richards held an open house and staged a party for the children, all of whom, according to Mining Life Editor Owen Scott, excelled at recitation.

In the summer of 1875, Henry, now boarding at the home of Mrs. Sarah Brown, got friendly with a young stonemason named George Schaefer, whose distinctive choice in headgear had won him the nickname of “Sombrero Jack.” Schaefer had two loves, each of which fueled the other: He loved to drink and he loved to steal. On September 4, 1875, he broke into laundryman Charlie Sun’s house and stole about $200 worth of goods, including two pistols. He offered Henry a cut if he would hide some of the loot in his room. Mrs. Brown found it and immediately informed Sheriff Harvey Whitehill, who arrested Henry, apparently hoping the arrest would prove to be a deterrent. Unfortunately, he neglected to tell this to Henry, and three days later, the boy wriggled up the jailhouse chimney and “skinned out,” his schooldays well and truly over.

Big changes had taken place in Mary Richards’ life, too. Late in 1874, she had met and fallen in “love at first sight” with Canadian-born carpenter Daniel Charles Casey, who came to New Mexico to seek his fortune. They were married by the Rev. W.W. Curtis on October 5, 1875, just a little while after Henry left Silver City forever.

Oddly enough, Mary’s adventurous life seems to have become singularly uneventful thereafter, if one can say that successfully raising six children in frontier mining towns is ever uneventful. In 1880, the family moved to Georgetown, where on January 13, Daniel Casey was appointed a justice of the peace by Gov. Lew. Wallace. Still later they moved to Clifton, then back again to Georgetown, where the 53-year-old Mary Phillippa Casey died of tuberculosis on the first day of the new century. Her husband Daniel died on December 2, 1912.

Influence on Billy the Kid

“A teacher affects eternity,” wrote Henry Brooks Adams. “He can never tell where his influence stops.” This was certainly true in the case of Mary Richards—who knows how much the brief time she spent with young Henry Antrim influenced the man he would become? And how remarkable—to this writer, at least—that apart from his mother, the two most influential persons in the life of the boy who was to become Billy the Kid (the second was, of course, John Henry Tunstall) were both English.

Frederick Nolan’s Tascosa: Its Life and Gaudy Times will be published this year by Texas Tech University Press. He recently received WOLA’s 2005 Glenn Shirley Award for his lifetime contribution to outlaw-lawman history

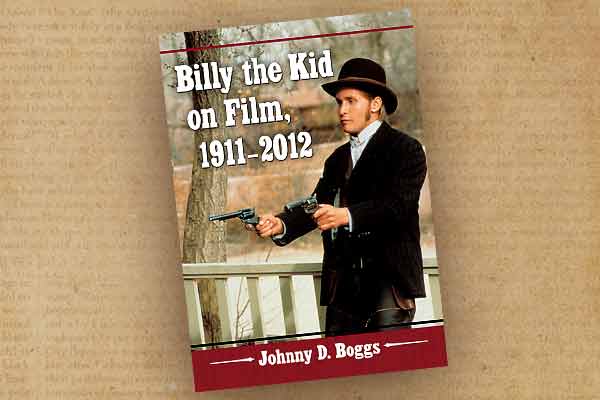

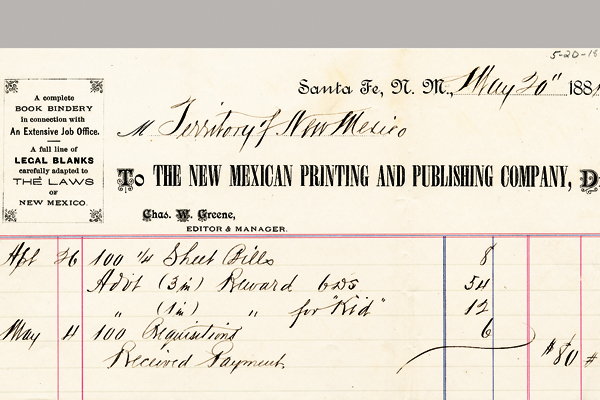

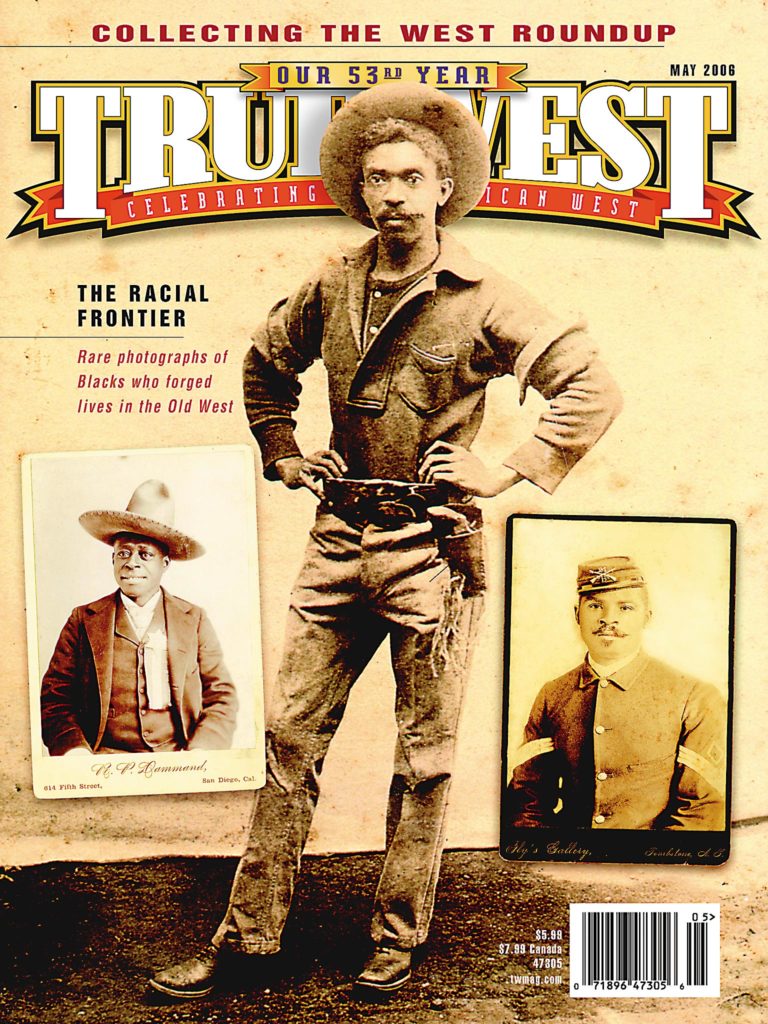

Photo Gallery

– By Bob Boze Bell –

– Courtesy Frederick Nolan –