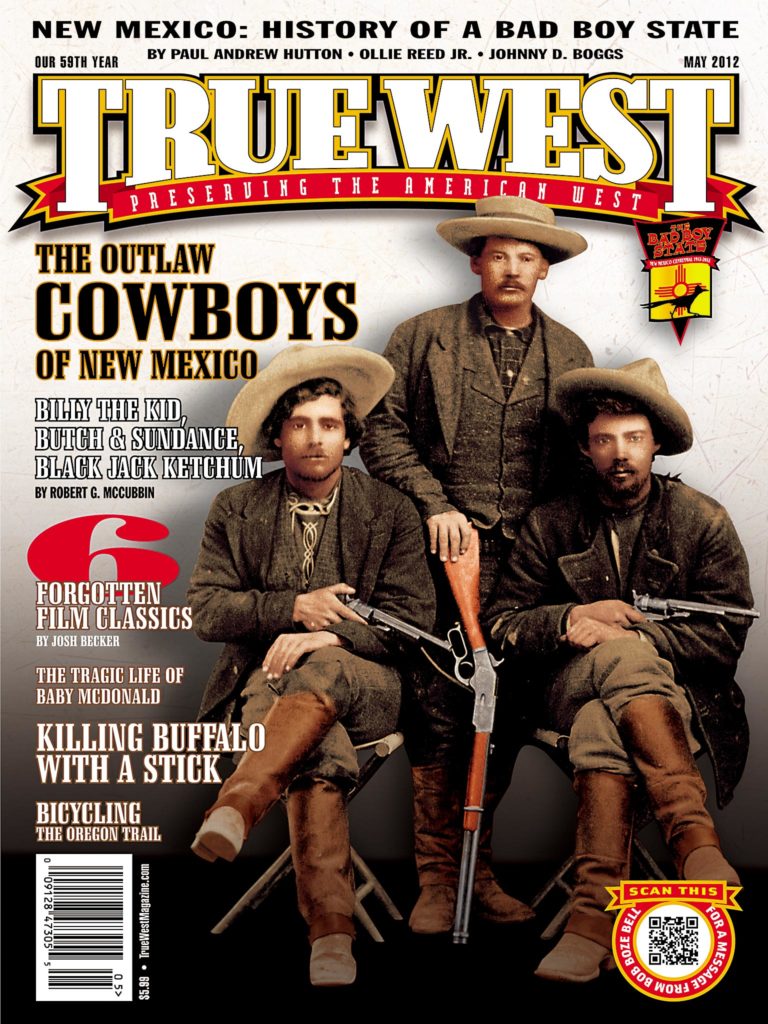

Josh Becker has watched 4,720 movies.

Josh Becker has watched 4,720 movies.

After 36 years in the film industry, 42 screenplays, 20 years’ worth of TV shows and seven feature films, he still would rather spend his time talking up the Golden Age of Hollywood, when studios actually made good movies. That’s why he signed on to write the column, Forgotten Film Classics, for True West. He wanted to share the Western movies he remembers and loves that some of us may have forgotten, as well as great classic Westerns he stumbled upon.

Becker gathers here six film classics he says Western fans should not miss, from the first Fox Western made after John Ford’s departure to a dramatization of real-life stagecoach robber Bill Miner.

Josh Becker is the internationally-known director of Xena: Warrior Princess and Hercules, has directed seven feature films and has been a proud member of the Directors Guild of America for 19 years. His latest book is Going Hollywood by Point Blank.

1948’s Yellow Sky

The success of John Ford’s My Darling Clementine in 1946, produced by Twentieth Century-Fox, was the spark that ignited the amazing revival of Westerns right after WWII, straight through the 1950s and well into the ’60s. Sadly for Fox, 1946 was also the same year John Ford quit working there after 26 years (Ford and Darryl Zanuck, head of Fox as a result of the 1935 merger, absolutely hated each other).

So, when Fox produced Yellow Sky in 1948, the studio hired screenwriter Lamar Trotti and cinematographer Joe MacDonald, both of whom had worked on Clementine. But instead of Ford, Zanuck hired stalwart, veteran director William A. “Wild Bill” Wellman (The Public Enemy, Beau Geste, Battleground).

Wellman was a straightforward, no-nonsense director who began his career directing Buck Jones Westerns for Fox in 1923. He did such a good job with these extremely low-budget films that after only four years as a director, and having never handled a big ‘A’ picture, he was surprisingly given the job of directing Paramount’s biggest movie of 1927, Wings, which went on to win the very first Oscar for Best Picture (though, strangely, Wellman wasn’t even nominated).

In 1943, Wellman directed the most realistic, disturbing Western yet made, The Ox-Bow Incident, with the first realistic depiction of an incensed, wrongheaded lynch mob (with a screenplay by Trotti).

Yellow Sky starred Fox’s two biggest young stars, Gregory Peck and Richard Widmark (in his fourth film), both of whom are terrific. It tells the highly-compelling and visually-striking story of a band of bank robbers setting off across a seemingly endless desert salt flat (shades of Hell’s Heroes) to escape the law. When the robbers are dying of thirst, they happen upon a ghost town called Yellow Sky; its only inhabitants are an old man and his tomboy granddaughter, a very cute, young Anne Baxter.

Why are the old man and the young girl still there? Something is making them stay, and the bank robbers are going to find out what it is. Not to mention that Baxter looks extremely sexy in her tight jeans. After a point, of course, the bad guys naturally turn on each other, and Peck and Widmark become worthy adversaries.

So, even though Twentieth Century-Fox didn’t have John Ford anymore, the studio still managed to make a tough, interesting, top-notch Western without him, and would go on to make quite a few more.

1951’s Fort Defiance

Fort Defiance pulls off what many more much higher-budget films don’t come close to doing—it gets nearly everything right; not in any monumental way, but just enough in every department to make it a good, solid, satisfying film.

In this John Rawlins-directed picture, Ben Shelby (played by Ben Johnson) returns from the Civil War looking for revenge on the soldier who never delivered a message to his unit, causing everyone to be killed, except him. When he gets to the traitor’s home, he finds the man’s old father and his blind brother (a very young Peter Graves) trying to run the ranch. Ben stays on as a ranch hand to wait for his enemy’s return. Along the way, he comes to really like the old man and the kid, and they really like him too.

The single best thing about this film is Johnson’s tough, but ingratiating, performance in one of his few leading roles. John Ford discovered him, and he had the lead in one of Ford’s films (Wagon Master), as well as Mighty Joe Young. But Johnson was best known as a durable, believable, Oscar-winning character actor. He had been a champion rodeo rider before going into movies, and it shows in this film—he does the best flying dismounts of any actor in Hollywood. Scene after scene, he comes galloping in at top speed, and he’s off the horse before it’s close to stopping.

Fort Defiance also has a wonderfully snotty, amusing performance by the underrated Dane Clark. He’s a wise-cracking, two-gun killer, and he hasn’t got any problem with that. But if you do, you’re in trouble.

Screenwriter Louis Lantz didn’t have much of a career, and his best credit was writing the story for the Marilyn Monroe/Robert Mitchum film, River of No Return. In this case, however, Lantz provided a well-constructed script that’s just loaded with good lines.

The pretty color photography, shot on spectacular locations outside Gallup, New Mexico, was by Stanley Cortez. Cortez shot Orson Welles’s classic, The Magnificent Ambersons, one of the most beautifully photographed movies of all time. In the silly facts department: Cortez was the younger brother of the 1920s Latin-lover movie idol Ricardo Cortez, whose real names were actually Jacob and Stanislaus Krantz. They were not Latino at all, but Jewish and from New York!

1953’s Ride, Vaquero!

Anthony Quinn began his career in 1936, most notably in C.B. DeMille’s classic Western, The Plainsman. (Quinn would marry DeMille’s daughter the next year.)

The Mexican-Irish Quinn spent the next 15 years in supporting parts in many movies, playing heavies and Indians (Chief Crazy Horse in They Died With Their Boots On, Chief Osceola in Seminole).

In 1949, when Marlon Brando came to Hollywood to begin his film career, Quinn played Stanley Kowalski in A Streetcar Named Desire on Broadway, thus bringing him into contact with director Elia Kazan. In 1952, Quinn costarred with Brando in Kazan’s film, Viva Zapata! and won the first of his two Oscars.

The following year, Quinn costarred in Ride, Vaquero! with Robert Taylor, Ava Gardner and Howard Keel, and steals the picture out from under all of them. His Mexican bandido, Esqueda, has as many tics, quirks and eccentricities as any of Brando’s screen characters, including scratching. Esqueda is either raging, terrorizing the countryside or crouching on his bed whimpering.

Taylor plays Rio, Esqueda’s adopted brother, and the most loyal, trusted member of his gang. That is, until Rio lays eyes on the wife of the new settler couple, Keel and young Gardner. Rio quits being a bandit and becomes the settlers’ ranch hand. He wants folks to believe he’s gone straight, but everyone, except Keel, understands what’s really taking place. It’s kind of an outrageous situation, and the filmmakers don’t know what to do with it, but nevertheless, it’s sexy.

I had the honor of directing Quinn in a 1994 TV movie. He was the biggest pain-in-the-ass actor I’ve ever worked with. He questioned every single piece of direction I gave him. He was also the best actor I’ve ever worked with. As difficult as he was, he delivered the goods on every take. And he was 79 at the time.

Ride, Vaquero! is a terrific early example of Quinn just exploding off the screen. It’s also a provocative, well-produced picture, with a strong, serious performance by Taylor, and it showcases Gardner at her dark, sultry, 23¼-inch waist, dimple-in-her-chin cutest. Heck, I’d become her ranch hand too.

1956’s The Last Wagon

Richard Widmark was a terrific movie star, with an exceptionally impressive acting range; he moved easily between psychotic hoodlums, heroes, cowards and intensely sympathetic good guys. Widmark also made 16 big screen Westerns. As he said, “I felt pretty comfortable with Westerns, apart from the fact that I couldn’t ride.”

He was modest, too; he rode just fine.

The Last Wagon is a wonderful example of Widmark at his charismatic best. He dominates the film without upstaging or eclipsing anyone else (although, for an A-movie, The Last Wagon has an oddly second-rate supporting cast).

Widmark plays the ridiculously named Comanche Todd, who leads a group of teens to safety after Indians massacred other members of their wagon train. Comanche Todd has a price on his head, but he’ll sacrifice himself for the sake of the kids.

The film is directed and cowritten by Delmer Daves, who had already made the excellent Westerns, 1950’s Broken Arrow and the original 1957 3:10 to Yuma. The Last Wagon deserves to be included with Daves’s best films (he also made two great WWII films: 1943’s Destination Tokyo and 1945’s Pride of the Marines). Daves began his long, distinguished career in movies as a prop boy on the epic silent Western The Covered Wagon in 1923.

Some fun facts: Widmark was married to the former wife of Henry Fonda, so some of Fonda’s kids were Widmark’s stepchildren (although not Jane or Peter). Also, Widmark’s daughter (not from Fonda’s former wife) married baseball legend Sandy Koufax.

1972’s Evil Roy Slade

Before Blazing Saddles came out in 1974, the funniest Comedy Western was the TV movie Evil Roy Slade. It stars John Astin—in his best part besides Gomez Addams from The Addams Family—as the meanest, most evil bad guy in the West.

Baby Roy is abandoned in the desert and is so mean that the wolves won’t take him in (so we’re told by narrator Pat Buttram, who played Mr. Haney on Green Acres).

Twenty years later, and still wearing a diaper, Roy is just as mean as he ever was. He is pursued by Dick Shawn playing the ultra-good guy Bing Bell, whose guitar is also a rifle. Due to the love of a good woman (Pamela Austin), Roy attempts to go straight. He gets a job in a shoe store owned by Milton Berle. If the shoe you’re trying on is too big, Roy will happily smack your foot with a ruler until it swells up and fits. Oddly failing in the shoe business, Roy sadly returns to a life of crime.

Evil Roy Slade was directed by Jerry Paris, a ubiquitous character actor from the 1950s-60s. He played one of the bikers in Marlon Brando’s gang in 1953’s The Wild One, a mutinous crew member in 1954’s The Caine Mutiny and Marty’s cousin in 1955’s Marty, not to mention Dick Van Dyke’s neighbor, Jerry the dentist, onThe Dick Van Dyke Show (of which Paris directed 84 episodes). Paris and the cowriter of Evil Roy Slade, Garry Marshall, would go on to make the TV show Happy Days, of which Paris would direct an astounding 238 episodes!

I’ve been quoting lines from Evil Roy Slade since I was in high school. At one point, a posse led by Mickey Rooney is chasing Roy, who arrives at a precipice. It’s a 10-foot jump over a thousand-foot drop (in front of a beautiful matte painting by the brilliant Albert Whitlock). Roy makes the jump. Rooney says, “One hundred dollars to the man who will make that jump.”

Then a guy rides past, and we hear him fall screaming into the abyss. Rooney says, “Two hundred dollars to the man who will make that jump.”

Another guy rides by and falls off the cliff. Rooney chuckles to himself, “I just saved $300.”

1982’s The Grey Fox

Real-life stagecoach robber Bill Miner was arrested in 1866, then served several stints in prison. He was released in 1901, a sad, dispirited, elderly man with no hope, no profession and entirely unsuited for the new century in which he found himself. Then, in one of the great scenes in motion pictures about the power of motion pictures, Bill sees a screening of the 1903 film The Great Train Robbery. The amazing possibility for a whole new future presents itself to him right there on the big screen—why not rob trains?

The Grey Fox is a perfectly realized, low-budget, Canadian production shot in scenic British Columbia. The film was brilliantly directed by Phillip Borsos, with truly stunning photography by the talented cinematographer Frank Tidy, who had already shot one of my favorite movies, and one of the most beautiful movies ever, Ridley Scott’s first feature, The Duellists. (I must admit, however, that after this exceptionally auspicious start, both Borsos’ and Tidy’s careers turned out to be highly disappointing.)

The best thing about The Grey Fox is that former stuntman Richard Farnsworth gives the quintessentially great performance of his entire career. If you keep your eyes peeled, Farnsworth has acted since 1937—A Day at the Races, with the Marx Brothers. I first became aware of him in 1973 as one of the bounty hunters inPapillon. I contend that it’s not possible to find anyone better than Farnsworth, either before or since the part of Bill Miner. Farnsworth achieved the incredibly rare film alchemy of entirely becoming the character he was portraying.

The Grey Fox is a beautiful character study, a fascinating piece of history, a prosaic action film and a rumination of a bygone era.