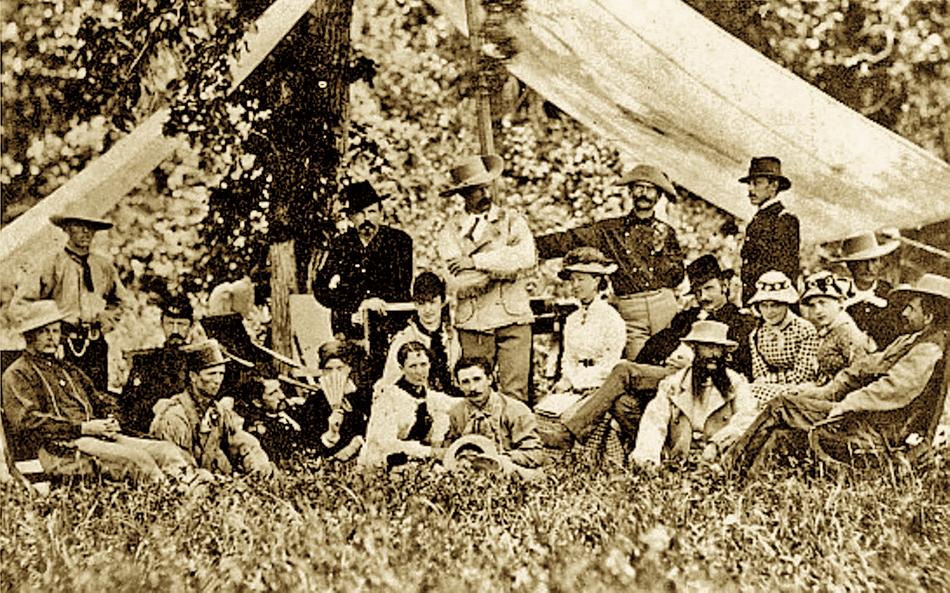

Wives and families accompanying their military husbands during wartime is nothing new in American history. Martha Washington spent winter encampment with her general husband during the American Revolution.

Wives and families accompanying their military husbands during wartime is nothing new in American history. Martha Washington spent winter encampment with her general husband during the American Revolution.

The wives of frontier U.S. Army servicemen during the last half of the 19th century, however, not only endured the hardship and fear of losing their husbands in combat, but they and their children struggled with heat, cold, illness and a lack of suitable shelter and food, as well as attack by hostile natives. Many of the women kept journals, wrote letters or, in later years, penned their reminiscences of their life in the American West.

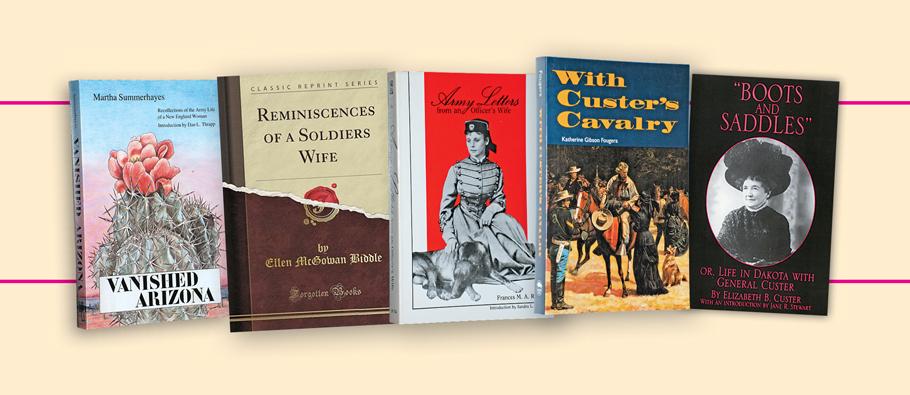

In Vanished Arizona, Martha Summerhayes described her life in the Arizona Territory during the 1870s. On her way to Camp Apache, Martha was apprehensive about encounters with hostile Apaches as darkness drew near. To soothe Martha’s troubled mind, her husband, Lt. Jack, confidently assured her they don’t attack at night, but “Just before daylight.”

While at the territorial post, Martha gave birth to a son, the first born to an officer at the camp. She received little assistance from anyone in caring for the infant. A delegation of Apache women did come bearing gifts, including a papoose basket, and an enlisted man helped once a week with the housework.

Posted in Ehrenberg during the hot summer months, Martha found it difficult to maintain a household. She had no butter, the hens laid few eggs and she was without milk for weeks at a time when the cows crossed the Colorado River to graze and did not return until the river fell again. Merely obtaining “safe” drinking water from the river also presented challenges. Assisted by local Indians, she would place the milky chocolate-colored water in barrels until the sediment settled to the bottom; then she poured the clear water into ollas. The 86-degree temperature of the drinking water was “a trifle cooler than the air,” which made it refreshing to Martha since the air registered 122 degrees in the shade.

Besides the heat, Martha had to contend with desert sandstorms. During the summer, people slept outdoors to escape the stifling heat, but when a sandstorm appeared at night, the family rushed indoors, half suffocated and blinded by the dirt. The next day, all the furniture had to be moved outside to clean. After one particular storm, she used a shovel to remove the sand from the floors.

Other wives had similar experiences, describing in detail their situations with family and home life on the frontier. Ellen McGowan Biddle, who had already accompanied her husband, Col. James Biddle, to duty stations in the South after the Civil War, recounted her 1873 arrival at Fort Riley in Kansas from Fort Halleck, published in Reminiscences of a Soldier’s Wife. She was fortunate that her furniture had arrived before her. As luck would have it, however, before she could become settled, the colonel received orders transferring him to Fort Lyon in Colorado. She had to repack everything! She also had to find another cook and housemaid, since none would be available on the plains.

In 1875, the Army transferred Col. Biddle to Fort Grant in the Arizona Territory. Although Ellen did not have a nurse, this particular journey was delightful, with “no Indians, the weather perfect, the children and myself well, and plenty of game for the Colonel, to shoot.”

Frances M.A. Mack married Fayette Roe shortly after his graduation from West Point in 1871 and was posted to Fort Lyon. Frances’s reminiscences, published as Army Letters From an Officer’s Wife, 1871-1888, provide a detailed description of frontier military life for a young woman. Newly arrived in Colorado, she learned how to address fellow officers: lieutenants were always called “Mister,” but sometimes the captains were called generals and first lieutenants addressed as majors. Frances recorded, “it is apparent to me that the safest thing to do is to call everyone general—there seem to be so many here.”

Illness on the frontier was something the women usually had to endure or else be sent back East. Sometimes the wives, whether on a military post or in transit, were lucky to have a doctor present to tend to their needs. When the Army transferred Lt. Roe from New Orleans to Montana, Frances fell ill, either from malaria or “too many scuppernong grapes at Pass Christian.”

Not able to walk or even stand up, Frances had to suffer the jolting of the heavy army wagon, which had been placed at the end of the long line to avoid slowing the progress of the men. When Frances overheard the Army doctor suggest she stay at the nearest ranch because she was too ill to continue, she feigned getting better and traveled inside the wagon on her hands and knees.

Written in a more literary style, Katherine Gibson’s memoir, With Custer’s Cavalry, provides a livelier look at life on the military post. While visiting her married sister, Mollie McIntosh, whose husband had died with Gen. George Custer at the 1876 Battle of the Little Big Horn, Katie married Lt. Francis Gibson at Fort Abraham Lincoln instead of going back to Washington, D.C. since her new family and friends would be at the post.

Katie, a confidant of Elizabeth Custer’s, quickly took to life on the frontier. Preparing her new quarters at one post, Katie slid strips of gunny sack in the floor cracks and under the doors to keep out the cold. While some women decorated the walls with pages from the Army and Navy Journals, Katie preferred worn canvas. To dress up the room, she draped bright calico cloth over boxes used as chairs and placed edged Army blankets on the floor as rugs.

Penning three books of her life with Gen. George “Autie” Armstrong Custer on the Western frontier—Boots and Saddles, Following the Guidon and Tenting on the Plains—Elizabeth was instrumental in developing the mythology surrounding her husband. Not only did she provide details about the events out West, but she also recounted her own life on the plains.

While Libbie rarely prepared meals for herself and her husband—they always seemed to have a cook or servant, even out in the field—she did note the availability, or absence, of food supplies. When asked what she considered a rarity, she responded that a feast had once been created over a cabbage that cost $1.50. Fresh eggs were such a luxury that when the opportunity came, she purchased several cases. The journey of 500 miles played havoc with these eggs. Crystallized eggs, in airtight cans, kept a long time and “were of more use to us than any invention of the day.” Fresh fruit and vegetables were also in limited supply, so when they did appear on the dinner table, it became an event.

While Libbie learned to cope with the ever-changing availability of foodstuffs, she never could deal with rattlesnakes. When traveling to the Dakota Territory, the troops encountered not just hostile Indians (the officers accompanying Mrs. Custer were under strict orders to shoot her if she was going to be captured), but rattlesnakes. At one camp, hundreds of soldiers cleared the brush and grass, disposing of more than 40 of the slithering creatures. This became a ritual whenever the soldiers halted for the night at a place with thick underbrush.

Libbie, unlike many other officers’ wives, wrote about the battles and skirmishes with the Indians. In Boots and Saddles, she described the natives’ continuing attacks on the garrison, her premonition of disaster and then the gathering of the women in her home after the men rode out in June 1876.

Not all military wives had to endure the deaths of their husbands in battle, like Libbie did, but all lived with that possibility. These women survived the rigors of frontier living, sometimes with complaints, many times with ingenuity, but always with the fortitude necessary to help settle the Western frontier.

Shelly Dudley is the wife of a former U.S. Marine Corps officer and mother of three sons, who all served in the military, including seeing action in two wars. She is the owner of Guidon Books in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Photo Gallery

– True West Archives –