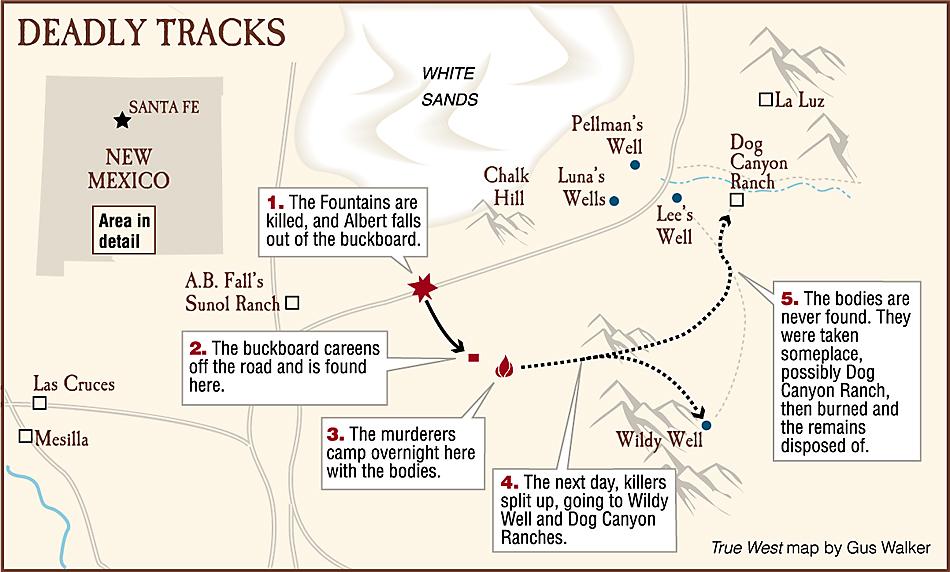

February 1, 1896

February 1, 1896

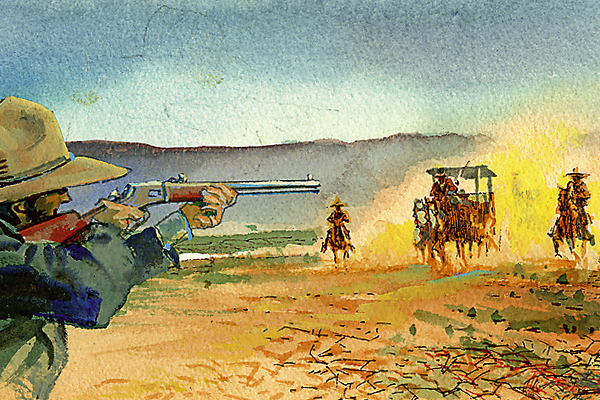

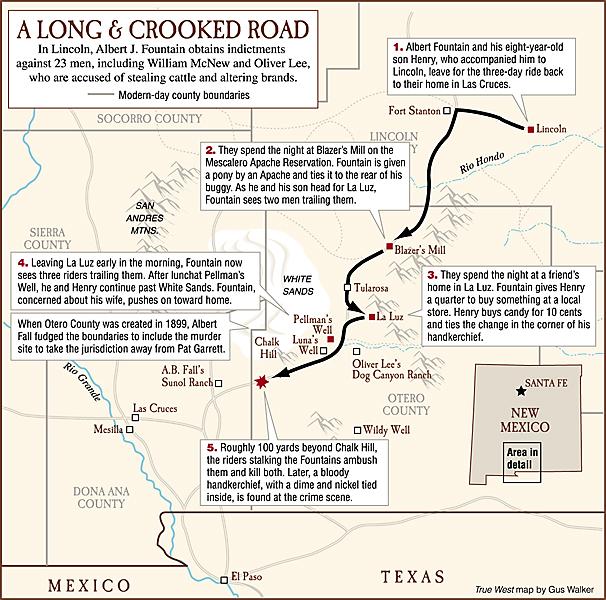

Albert Jennings Fountain is agitated. It’s cold and windy, and his young son is coming down with a cold. Fountain is anxious to get the eight year old home to his mother, but his discomfort has more to do with three suspicious horseback riders who have been tailing him for some time.

These are not the first riders to trail him on this ride. Some 40 miles from Las Cruces, New Mexico, Fountain encountered the mail carrier on the way to Tularosa. Reining up, the postman had pulled alongside, and Fountain asked him, while pointing off in the distance: “Do you know who those horsemen are?”

The mailman admitted he didn’t know them, and mentioned they did not appear to want to meet him on the road: they “took out across the plain” at his approach, he said.

Although the mailman encouraged Fountain to ride with him to a nearby ranch to wait and then ride back together on Sunday morning, Fountain studied the scene and told him, “No, I will drive on. Good-bye.”

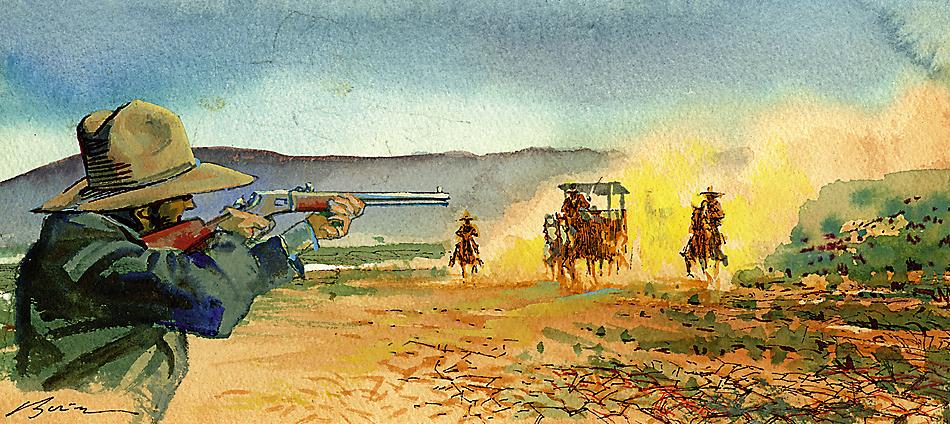

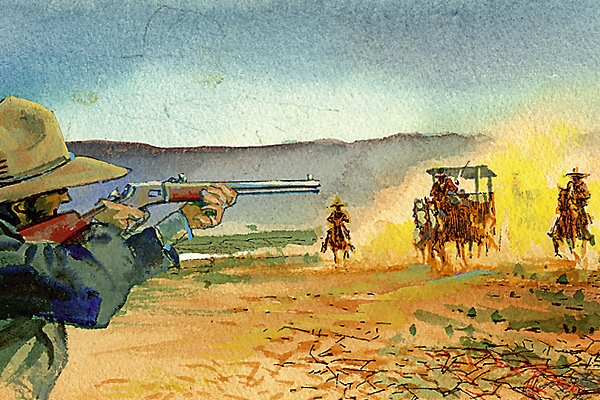

Now, about five miles from his encounter with the mailman, Fountain sees the three horsemen disappear in the sand hills. He proceeds cautiously. As he approaches Chalk Hill, two riders suddenly come out of the brush in a threatening manner. Fountain whips his horses into a run and comes over the hill. Up ahead, one of the riders has dismounted and is on one knee, behind a bush. Before Fountain can retrieve his rifle, the assassin stands and fires, hitting Fountain in the chest and knocking him off his feet. The spooked horses turn and go off the road in

the sand as Fountain topples from the buggy.

After putting Fountain’s lifeless body on one of the buggy horses, the killers draw straws to see who will kill the boy (in one version, this happens at the first camp, five miles ahead). One of the cowboys draws the short straw. He calmly gets up, walks over to the crying boy and grabs him from behind, covering his mouth with one hand and slitting his throat with a knife in the other. In terror, the boy grabs the man’s arm as his scream muffles down to a gurgle. His hand still gripping the man’s arm like a vise, the boy slowly loses consciousness and then goes limp.

The brazen killers ride eastward, splitting up with the cowboys packing the bodies and heading toward Oliver Lee’s Dog Canyon Ranch. The rider on the big white horse heads to Wildy Well Ranch.

The Bizarre Twists & Turns of a Case Going Nowhere

The three suspects, Oliver Lee, Bill McNew and Jim Gilliland, are deputy marshals for Doña Ana County, where the killings took place, in addition to being deputy U.S. marshals. Stymied by the fact that the authorities who are supposed to be looking for the killers of the Fountains are lawmen themselves, the frustrated governor of New Mexico, William Thornton, hires an outside lawman, none other than Pat Garrett, who is now living in Ulvalde, Texas. In addition, Thornton hires the Pinkerton Detective Agency to launch its own investigation.

Garrett is hired at $150 a month, plus a promise of $8,000 if the murderers are arrested and convicted. At the end of February, three weeks after the murder, Garrett is in the saddle, but he and his men turn up nothing.

Garrett does see Lee with attorney Albert Fall on the streets of Las Cruces and in nearby El Paso, Texas. On the urging of Pinkerton agent John C. Fraser, Garrett meets with Fall at his office in Las Cruces. Fall talks freely and readily castigates Fountain’s character, repeating a scandalous rumor that Fountain was caught in a “compromising position” with his daughter, and that’s why he skipped

the country.

As if things could not get more strange, one of Garrett’s lawmen partners brought in by the Republicans, Charles Perry, leaves town with more than $7,000 in Chaves County tax funds and flees to South Africa. Soldiering on, Garrett runs for the office of sheriff in Doña Ana County. He wins. But then he is powerless in the Fountain case until the grand jury returns its indictments.

As he waits, Garrett heads to Tularosa and drops into Tobe Tipton’s saloon, where he encounters Lee, Fall and George Curry, plus another local. Garrett sits down opposite Lee, and they play poker for three days and nights.

After this incredible marathon game, Garrett confronts Lee, asking him if he will surrender if the grand jury indicts him. Lee responds, “Mr. Sheriff, if you wish to serve any papers on me at any time, I will be here or out to the ranch.”

As we shall see, the story doesn’t quite go down this way.

Shoot-Out at Wildy Well

After being hamstrung for some time by Fall and his control of the courts, Garrett manages to arrest McNew and another suspect without incident. He takes his time about going after Lee and Gilliland. When two of his deputies spot the pair at W.W. Cox’s ranch, Garrett has a good hunch where they will go next.

Riding toward Lee’s satellite ranch, Wildy Well, on July 10, 1898, the sheriff and four deputies pick up the trail and stop about a mile from the ranch. Dismounting, they continue on foot. One of the deputies even takes off his boots and continues in his stocking feet, banking on the element of surprise.

Garrett has been here before. When he tracked Billy the Kid and others to Stinking Springs in December 1880, he had wanted to rush in and arrest the outlaws in the middle of the night. He was overruled by calmer heads and was forced to wait until dawn.

At any rate, Garrett and his deputies barge into the Wildy Well ranch house in the dark and scare a sleeping family half to death. The element of surprise is blown. Lee and Gilliland, having awaken from their sleep on the roof, rout Garrett and crew in a chaotic gunfight. One of Garrett’s deputies is mortally wounded. Garrett is forced to walk off and leave his deputy behind. It is the most humiliating experience of Garrett’s life.

Given the disastrous outcome of the Wildy Well fight, the Kid story might have ended differently if Garrett had barged in there, instead of waiting.

The View From Oliver Lee’s Front Porch

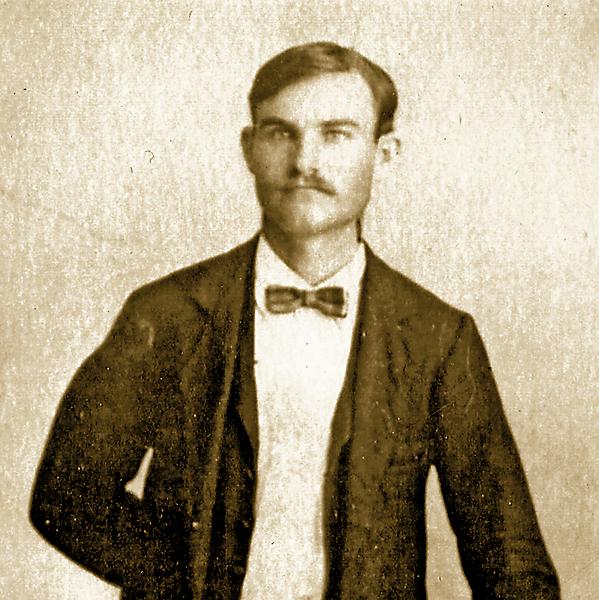

Anyone who heard Oliver Lee laugh never forgot it. The staunch Southern Democrat (until 1912, when he changes parties to become a Republican) is also a teetotaler: he neither drinks nor smokes. He is well read and reportedly has one of the finest libraries in the state. His friends and supporters call him “Dad” Lee, and they think enough of him to elect him to high political office on numerous occasions.

At the trial for the killing of the Fountains, swooning ladies send Lee flowers. One Eastern woman gushes of him: “With quick eyes and unobtrusive manners, he carried himself as softly and easily as if he were at a tea party. I was amazed as his low voice and control, and a certain social grace.”

And yet, all the tracks in this case lead directly to his front door. More important, he has the motive: he was looking at 10 years in the pen if Fountain had arrived in Mesilla.

One thing is certain: if you could hear Lee now, he’d be laughing that laugh.

The TrialTom Catron vs Albert Fall

Three years after the killings, on May 26, 1899, the case against Oliver Lee and James Gilliland finally comes to trial in Hillsboro, New Mexico. After the indictments are read, Lee turns to one of his attorneys and says, “My God, Fergusson, they are not accusing me of the murder of a child.”

The crafty Lee “doth protests too much.”

Albert Fall examines Pat Garrett on the witness stand, which leads to this bizarre exchange:

Fall: “When this evidence came into your hands, why did you not apply for a bench warrant?”

Garrett: “I didn’t think it was the proper time.”

Fall: “Why didn’t you think it was the proper time?”

Garrett: “You had too much control of the courts down there.”

When Lee takes the stand, women weep and give him a “soft patting of hands.” Lee claims he didn’t know he was a suspect until several days after the disappearance. He tried to give himself up, but was refused.

The prosecution notes that boot tracks found at the scene of the crime match Lee’s boot heels, his horse matches the horse seen in the area and the tracks led to his house. Yet all this is circumstantial; the prosecution does not even have the dead bodies.

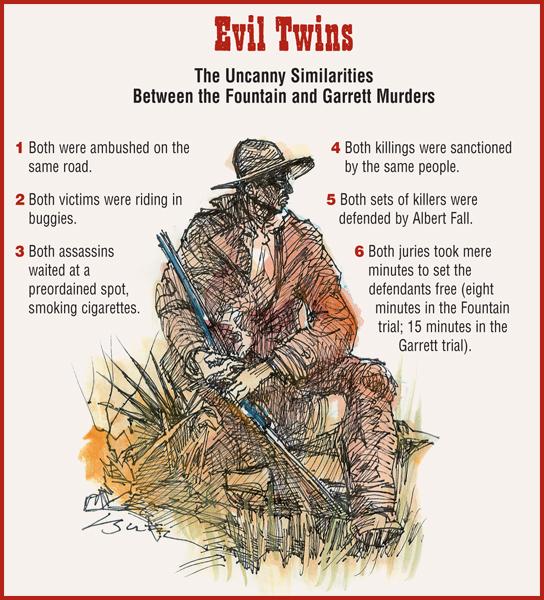

The jury takes less than eight minutes to reach a verdict of not guilty. The locals cheer. The congratulations go on for half an hour, with the celebration continuing into the night.

All the other charges against Lee and crew are dropped, even though he killed a deputy sheriff. They get off scot-free.

Aftermath: Odds & Ends

In 1915, Bill McNew shot and killed the husband of Jim Gilliland’s sister, Lucy. She wrote a letter to the Fountains: “If I had done my duty on the stand (although it would have ruined my brother), it is possible my husband would still be alive.” McNew continued ranching and died in 1937.

Gilliland sold his ranch in 1937 and eventually moved to Hot Springs (Truth or Consequences). One time while he was drinking, he confessed to B.O. “Snooks” Burris that he had killed the boy and that the bodies were buried on his ranch. He gave Burris a Masonic pin and asked him to return it to the Fountains after he was gone. The Fountain family pronounced it authentic.

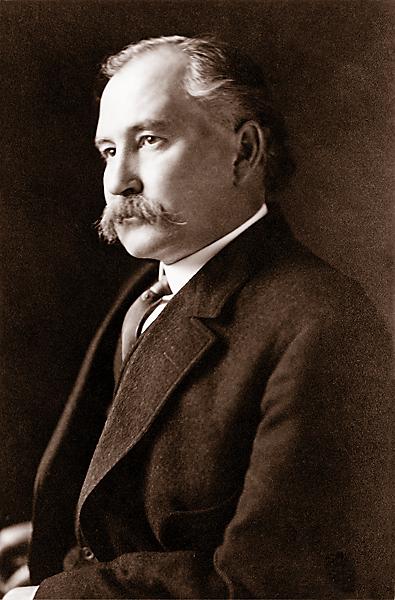

Albert Fall rose to national office, first as a New Mexico senator and then as secretary of the interior in the Warren Harding administration. Fall resigned in 1923 after he received a $100,000 kickback from an oil company in what became known as the “Teapot Dome Scandal.” The “Fall Guy,” as he was ever after pegged, served a year in the pen, lost much of his wealth and died a pauper in 1944.

Oliver Lee bought a new ranch and, like Fall, switched parties to become a Republican, serving for many years in the New Mexico legislature. He died respectable and wealthy in Alamogordo in 1941.

Recommended: Murder On the White Sands: The Disappearance of Albert and Henry Fountain by Corey Recko, University of North Texas Press.

Photo Gallery

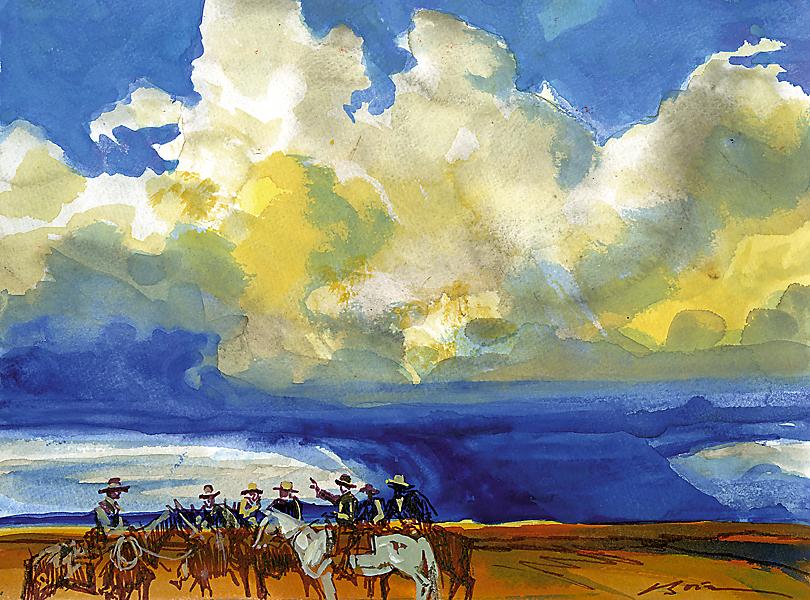

– all photos true west archives; all Illustrations by Bob Boze Bell –

By the time Fountain sees the riders, it is too late.

A posse led by Fountain’s son Albert finds the buggy the next day. Not only are the bodies missing, but so are Fountain’s Winchester rifle, a dagger, a canteen, a lap robe, an Indian blanket and a quilt. And, of course, all the indictment papers.

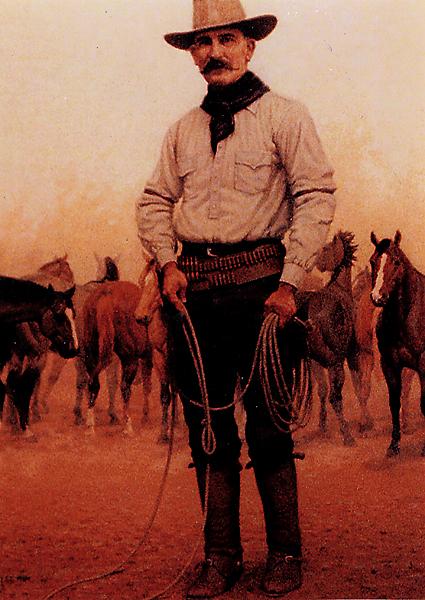

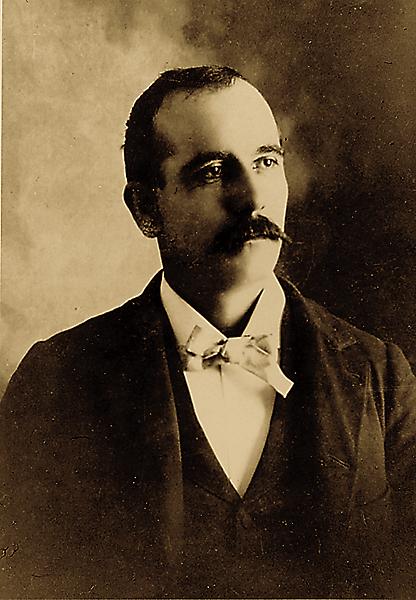

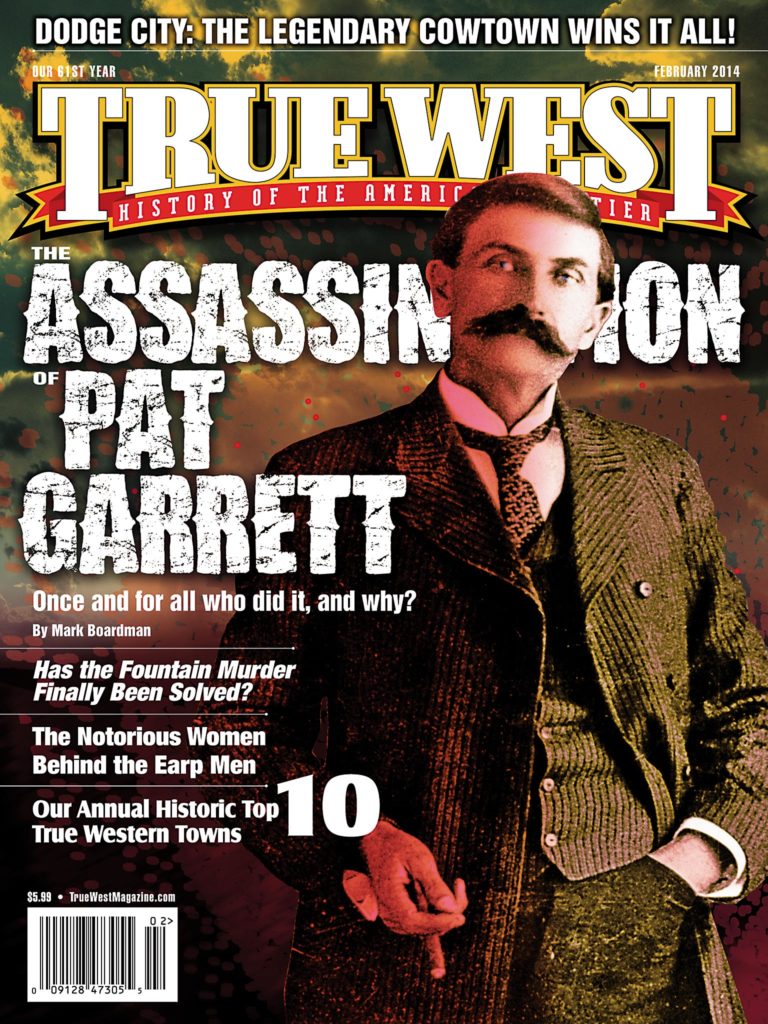

Shown at right is the only known photo of young Henry Fountain (on the left), with his grandmother and a cousin, circa 1893. Plagued by death threats, his father (left) is stubborn and dedicated: he has already sent 20 rustlers to the pen, and he has his sights set on Oliver Lee and crew. Fountain’s wife supposedly talked him into taking their eight-year-old son as a hedge against violence. Surely, she reasoned, nobody would harm a child.

“The child was nothing more than a half breed and to kill him was like killing a dog.”

—James Gilliland

Although only three horsemen are spotted by the mail carrier before the Fountains are ambushed, Oliver Lee likely has several more of his best hands and neighbors with him. After all, to them, they are fighting for their homeland against a corrupt official. Today, some historians believe seven men were in that party.

—Pat Garrett