“I consider it a damn good outfit,” George W. Hennessey once said of the infamous Hash Knife Outfit at the Aztec Land & Cattle Company, at one time the largest cattle ranch in Arizona and a brand still going strong today at northern Arizona’s Babbitt Ranches.

“I consider it a damn good outfit,” George W. Hennessey once said of the infamous Hash Knife Outfit at the Aztec Land & Cattle Company, at one time the largest cattle ranch in Arizona and a brand still going strong today at northern Arizona’s Babbitt Ranches.

“They were all good cowboys and good men. The ones I knew made something for themselves, ran businesses or held public office.”

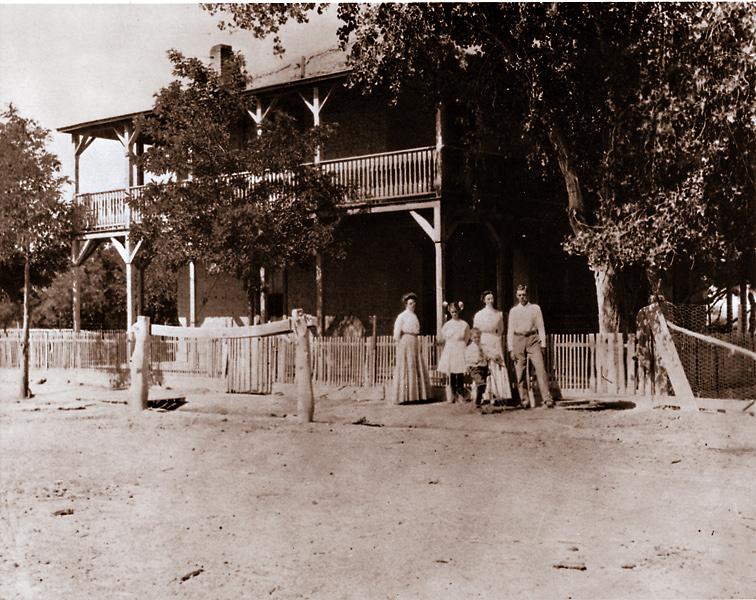

Of course Hennessey would remember them that way. Those close to him knew he was a good-hearted, optimistic man who seldom had a bad word to say about anybody. Born in Mason County, Texas, on the fourth of July in 1877, Hennessey first began working with cattle in 1891 and moved to Holbrook in 1898. William Smith, who grew up in Holbrook and served as mayor from 1961-1965, remembered Hennessey as “Neat, clean, good looking, kind and gentle.”

But despite Hennessey’s friendly demeanor and his sentimental defense of the outfit, there is no question that the Hash Knife was once notorious for its roughneck cowboys. Company hands were known to terrorize Holbrook on a Saturday night, and several were involved in various shoot-outs, robberies and rustling escapades.

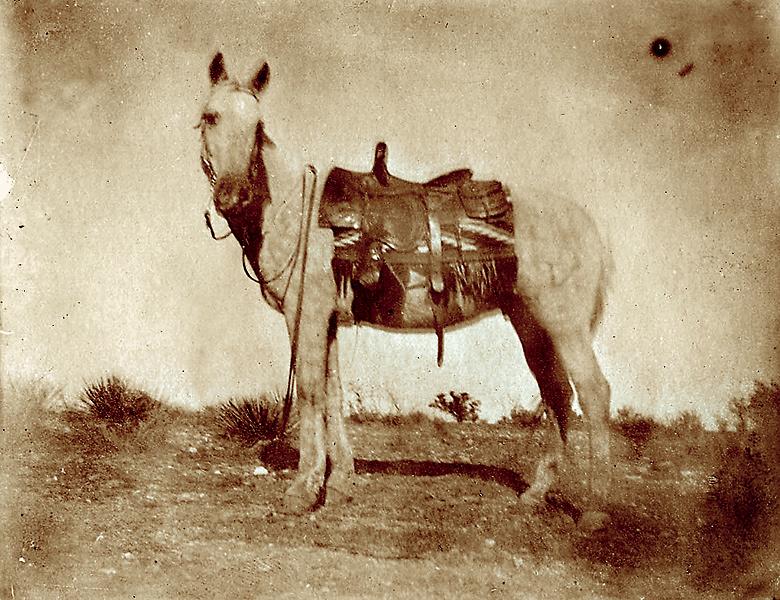

The Hash Knife brand, named for a common kitchen tool, originated in Texas. During the 1880s, the outfit’s association with the notorious Millett brothers of Baylor County, as well as an 1884 shoot-out involving some Hash Knife cowboys in Stoneville, Montana, had already tainted the brand’s good name. When the company expanded to a large range between Holbrook and Flagstaff in 1884, the owners hoped the outfit would shed itself of its unsavory reputation. Unfortunately, such a cleansing was not forthcoming. By the time Capt. Burton C. “Cap” Mossman was hired as superintendent in 1898, rustlers and outlaws seemed to be rampant both inside and outside the company.

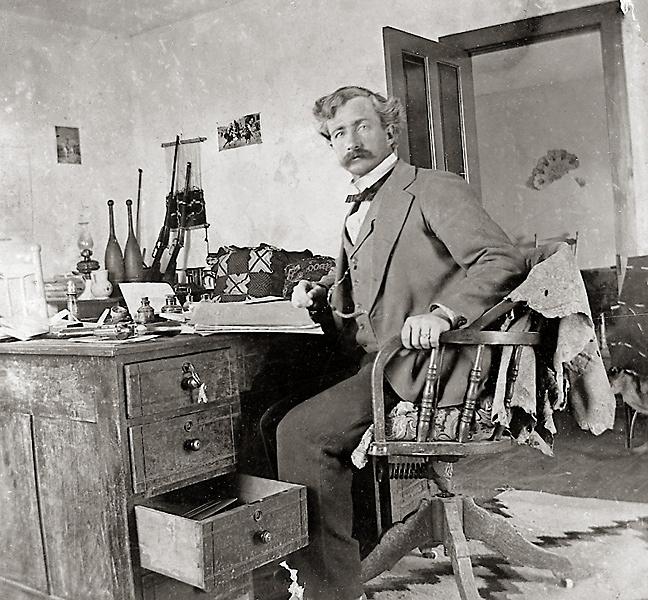

Mossman set to work cleaning house, firing half the crew within a month. He was assisted by foreman Benjamin Franklin “Frank” Wallace, a man Mossman had worked with before and ended up hiring soon after joining the Hash Knife. Wallace in turn hired Hennessey, and the two became lifelong friends.

During Hennessey’s time with the Hash Knife, the outfit was sold in 1901 to the Babbitt Brothers in Flagstaff. Hennessey fell in with approximately 30 other hands working under Mossman and Wallace. A few questionable characters may have still been in the group, but “It wasn’t a mean bunch,” Hennessey insisted, “just happy to return trouble.”

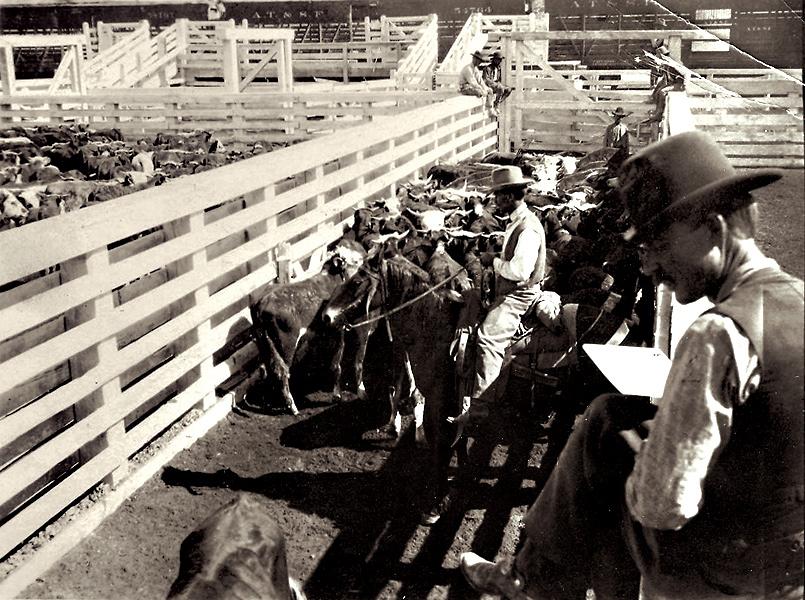

Its unseemly reputation aside, the Hash Knife was also suffering from over-populated ranges, feed shortages, the harsh winter of 1898-99 and a four-year drought. As such, Mossman received orders to liquidate the stock from Arizona. He sold roughly 33,000 cattle for $14 a head and began a series of roundups for shipping. In his later years, Hennessey had fond memories of those days. “We ate breakfast about 4 a.m. and wrangled our horses,” he said. “Sometimes we’d circle for 20 miles in a day, bringing the cattle in. Generally, we got a little rest in the afternoon. We’d come in at night in time to get the herd together and hold it overnight. Then everybody would stand three hours guard at night.”

Hennessey was fond of the men he worked with at the ranch. “It makes my blood pressure raise when someone comes out with the phrase that ‘Hash Knife outlaw outfit,’” he once said. “The Hash Knife had the name of being a hard drinking, hard fighting outfit, but I never worked with a better bunch of men.”

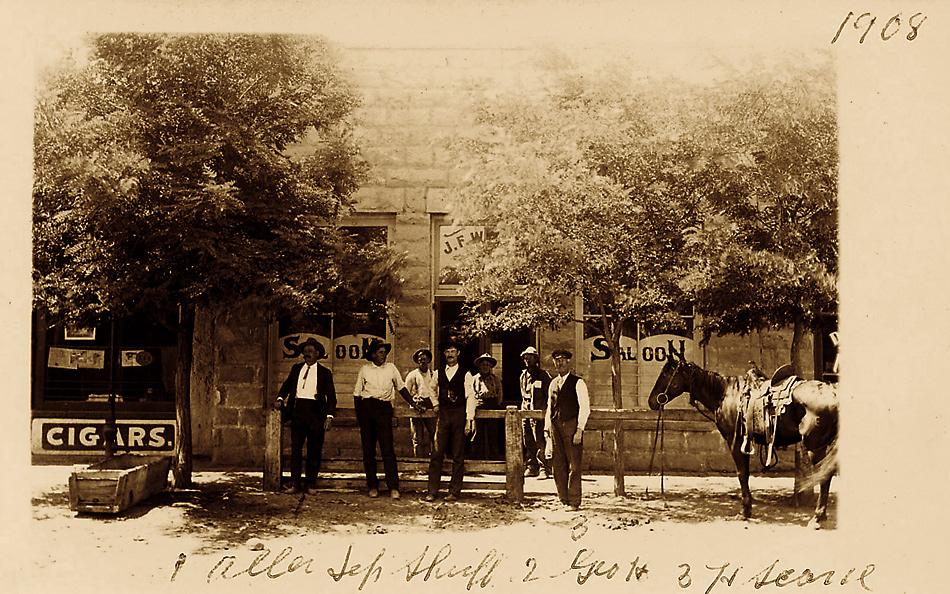

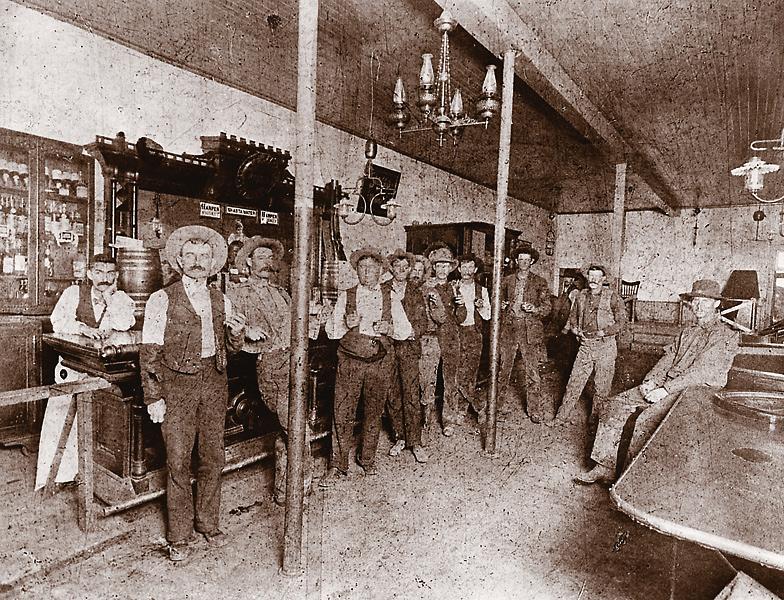

At the time Hennessey worked in Holbrook, the cowboys had to hand their six-shooters over to Sheriff Joe Woods when they came to town. Gone were the rowdy days at the Bucket of Blood Saloon, Holbrook’s most notorious drinking hole. “Our most fun was to get on a horse and get throwed off,” Hennessey said. “We enjoyed the life [of a cowboy] very much. There was no responsibility, only to just work. You had to be a pretty good cowboy to hold your job with the Hash Knife.”

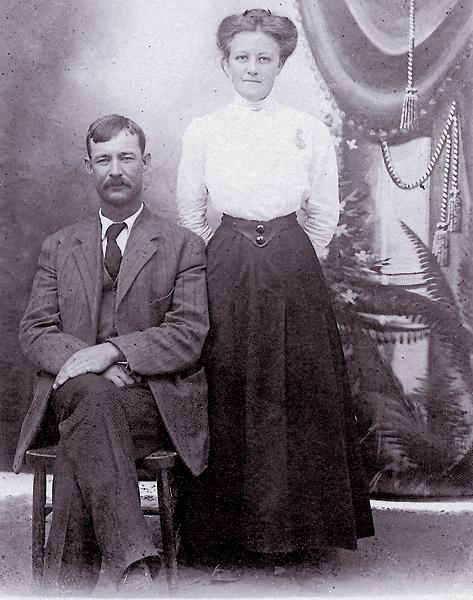

After shipping out the final nine train cars of cattle in September 1900, Capt. Mossman resigned. Hennessey left a few months later and went to work for the Wabash Cattle Company before going into business for himself in 1903. He began by purchasing $1,200 worth of cattle from Hubbell’s Trading Post in Ganado with $200 and a promissory note for the rest. By 1907 he was able to help his relatives pay off their mortgage in Texas and even ran the Bucket of Blood Saloon for about a year. In 1911 he married Frank Wallace’s daughter Frances in Adamana. His personal brands, the Slash T Slash and the XVL, became well known throughout northern Arizona.

Marriage and cattle did little to slow down Hennessey. “I got into the cattle business, and I made Holbrook my headquarters,” he recalled in a 1967 interview. “First thing I knew, I was in politics!”

Indeed, in 1917 Hennessey was unknowingly elected the first official mayor of Holbrook. “I wasn’t even a candidate, and I didn’t even go in and vote,” he explained, adding that he was out rounding up cattle that day. “Then a bunch of fellows came riding out from Holbrook. My father-in-law said, ‘You’re the mayor of Holbrook.’ I said, ‘Hell, I’m not even running.’ He said, ‘Well, you’re elected anyhow.’”

The legend of Hennessey being hog-tied and carried back to town, he said, was untrue—although his friends still joked about the tall tale for years.

He served as mayor for two years and continued ranching until he sold his outfit in 1932. The family—George, Frances and their two daughters—moved to Phoenix in 1934. Hennessey went to work as a cattle buyer, appraiser and field man for various banks. At First National Bank of Arizona, he became fondly known as “Uncle George.” He later confided that he enjoyed his position mostly because it allowed him to continue working out on the open prairie he so loved. Of his eventual retirement, he commented, “I think I’d enjoy myself a hell of a lot better if I was out on the range.”

He and Frances busied themselves with attending various functions held by their friends and business associates. Many times, the banquets were held in Hennessey’s honor. He also became a favorite subject of area newspapermen who diligently reported on his participation in rodeo parades and his attendance at various gatherings. In 1957, when the Navajo County Sheriff Posse began using the Hash Knife brand, the posse made Hennessey an honorary member.

He was not far off when he had said many of his associates at the Hash Knife were good men. Close friends of the family included writer Roscoe G. Willson, pioneer cowman Will C. Barnes, Yavapai County Sheriff Buckey O’Neill, agricultural agent Charlie Pickrell, ranchers Barney Stiles and Homer “Uncle Dick” Grigsby, and many others associated with the cattle industry. Hennessey not only maintained close contact with his old friends, he also defended them as needed. Author Frazier Hunt, who wrote Cap Mossman: Last of the Great Cowmen, was later accused by various historians of plying his subject with a bottle of whiskey during their interviews together. The result, they said, was more than a few skewed facts in Hunt’s book, which Hennessey called a lot of “damned lies.”

Hennessey’s cronies truly appreciated his friendship, often roasting him with stories about owning no shoes other than his beloved cowboy boots, and the time he chopped the toes off of his tight shoes as a boy in Texas. “I recall the dinner we had at the ‘Flame’, you and I,” Hennessey’s friend Sam Turner wrote in a 1957 letter. “It was such a treat for me recalling the old times, and just the pleasure of being with you was in itself so worthwhile.”

Even Sen. Barry Goldwater wrote Hennessey a letter, congratulating him on turning 90 years old in 1967.

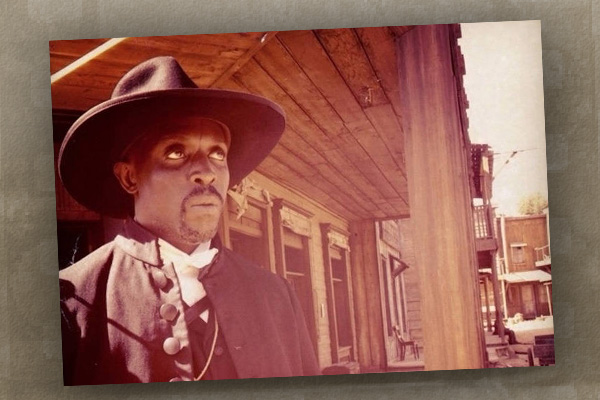

When The Arizona Republic interviewed Hennessey one last time in 1970, he was touted as the last true Hash Knife cowboy. He was also the last surviving charter member of the Arizona Cattle Growers’ Association, a former Navajo County supervisor, a member of the Masonic Lodge in Holbrook since 1912 and a member of the Order of the Eastern Star at Holbrook for 50 years. To his associates at First National Bank, he was a welcome presence at the annual breakfasts held throughout the region. To his wife and daughters, he was forever the gentle pillar of strength. To his grandchildren and great-granddaughters, he was the kind bearer of candy. And to his many, many friends, he was the jovial, business-smart old cowboy he had always been.

George Hennessey died in 1973 at the ripe age of 95 after a long, full life and few regrets. Books about the Hash Knife and Holbrook mention him only in passing. His family and admirers, however, still praise him as the last of the Hash Knife cowboys who honored the brand and was a solid influence on the cattle industry in northern Arizona during the 1900s.

Jan MacKell is the great-granddaughter of George W. Hennessey and the great-great-granddaughter of Frank Wallace. Her latest book is Red Light Women of the Rocky Mountains. She recently relocated from Cripple Creek, Colorado, to Prescott, Arizona, to work at the Sharlot Hall Museum.

Photo Gallery

– All images courtesy Jan MacKell unless otherwise noted–

– Courtesy Suzanne Peterson –