In the spring of 1889, the U.S. government faced a monumental task—opening the Unassigned Lands, nearly two million acres in modern-day central Oklahoma, to non-Indian settlers. Tens of thousands of would-be landowners were expected to participate, looking to grab 160-acre plots of free land.

In the spring of 1889, the U.S. government faced a monumental task—opening the Unassigned Lands, nearly two million acres in modern-day central Oklahoma, to non-Indian settlers. Tens of thousands of would-be landowners were expected to participate, looking to grab 160-acre plots of free land.

A man was needed to keep the peace and to enforce the law, ensuring people did not stake out property prior to the start time of high noon on April 22. That man was Thomas B. Needles, U.S. marshal.

Sort of. A few days shy of his 54th birthday, the merchant and banker from Nashville, Illinois, was a former senator and state auditor, but he had no law enforcement experience. His father had once been a county sheriff, which was the closest the son ever got to a badge and gun.

But President Benjamin Harrison was rewarding fellow midwestern Republicans for helping his recent election, and Harrison decided Needles would make a perfect U.S. marshal for the new district.

Needles reached his bailiwick on April 1. A newspaper called him “fat” and “amiable,” and predicted that he wouldn’t last long in the job. Undeterred, he picked four men as his deputies and assumed command of dozens of others who were already in the region.

Since some of the Unassigned Lands were in the Kansas District, overseen by U.S. Marshal William C. Jones, two law officers were technically in charge, as well as the U.S. Army troops sent in to help out. But Jones was a lame-duck Democrat, not long for his post, so he tended to cede power to Needles.

Keeping out “Sooners” was near impossible, particularly due to the presence of “legal Sooners,” people allowed in the Unassigned Lands prior to the Land Rush—railroad workers, surveyors, federal employees and lawmen. Many of those men wanted their own free land, so why not stake out some prime spots before anyone else could get there?

Anecdotal evidence indicates some legal Sooners did just that, including Needles. He and some compatriots staked out attractive lots in Guthrie. The government land office later denied his and five of his deputies’ applications. To counter that tactic, some legal Sooners illegally sold their claims before they were filed with the land office.

Needles continued in his job for another four years, until Harrison lost his reelection bid to Democrat Grover Cleveland. The highlight of the marshal’s tenure: ordering Deputy Marshal Heck Thomas to go after the Dalton Gang in 1891. Thomas was hot on the gang’s trail when most of the members met their demise in Coffeyville, Kansas, the next year.

In 1893, Needles moved back to Nashville, Illinois, where he was elected again to the state legislature, continued banking and died in 1914. But he had one more brush with the West; in 1897, Needles was appointed to the federal Dawes Commission, which, among other duties, wrested control of millions of acres from Indian tribes and opened them up for settlement.

That time, folks did not get a Land Rush; the Feds sold the plots.

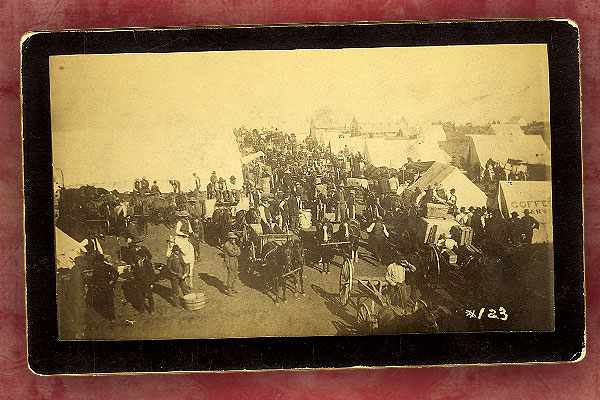

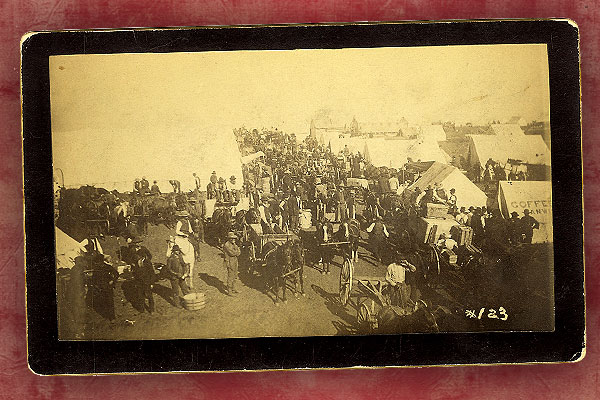

Photo caption: This crowd stands by for the Land Rush to officially commence at noon on April 22, 1889. More than one settler, who had properly waited for the gunshot to begin the race, came upon a spot already claimed. In at least one case, the settler complained to the Sooner—only to have a badge and gun flashed at him. The guy wisely moved on. – Courtesy Heritage Auctions, June 2008 –