Long before the 1993 movie Tombstone was produced, the screenplay by Kevin Jarre had gotten the attention of a great many people.

Long before the 1993 movie Tombstone was produced, the screenplay by Kevin Jarre had gotten the attention of a great many people.

Everybody who read the script was familiar with the characters in it and the mythical framework of the story. How could they not be? Wyatt Earp, Doc Holliday, Earp’s brothers Virgil and Morgan, Johnny Behan, the Clantons and the McLaurys, and the events that led up to the gunfight behind the O.K. Corral had been worked and reworked in every conceivable manner, by masters and by hacks. The story has been gripping the imagination of filmmakers since the early 1930s, only a few years after Wyatt’s death. It has been used to create myths and to debunk them.

But Jarre was able to reach deep inside that story and turn it into an operatic epic, more colorful and grander than anyone before him, including John Ford. He did it by recognizing and respecting the facts with uncanny accuracy. That’s not a small thing.

Like Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather, Tombstone colors a routine genre with new wit and brilliantly realized characters to the extent that it made people who knew the story care about it anew, and attracted those who had never heard of it. His script helped people not only appreciate the history, but also the era, when greed and ambition, chaos and character were intertwined. Like Deadwood, it’s a fantasy framed by fact.

One only has to compare Tombstone to Lawrence Kasdan’s competing picture, Wyatt Earp, to understand how anemic history can be when earnestness supersedes drama. Kevin Costner, who plays Wyatt Earp in Kasdan’s version, owned Jarre’s script initially, but he passed it on to Kurt Russell and Andrew Vajna. Costner wanted to make a picture he had every reason to think would be a definitive historical piece. He succeeded in that, except the movie isn’t fun or thrilling—you’ll find no joy in Costner’s Mudville.

The three things that make Tombstone better than it might have been, in the wrong hands, are: Val Kilmer taking the Brando prize as Doc Holliday, Kurt Russell’s sharp sense of economy in keeping his character squinty and restrained, and Jarre’s script, first and foremost.

Anyone who has read the screenplay, which is freely available on the Internet, can see that the best scenes in the picture are true to the script, for which we can thank Tombstone’s uncredited director Kurt Russell.

The sequence in the film that shows Wyatt taking over the faro game at the Oriental Saloon and running into Doc Holliday has not been touched, and it’s brilliant. Lines stay with you: “Go ahead,” Wyatt says to the bully Johnny Tyler. “Skin it. Skin that smoke wagon and see what happens.” Doc, seeing the humiliated and bleeding Tyler approaching Wyatt with a shotgun, says in his glib, dandified drawl: “Why, Johnny Tyler, you madcap.”

In that moment, we understand what these two men have in common—an almost casual disregard for the vermin who live in the periphery of their world. We’re constantly being reminded of this lesson: first, with the man who abuses Wyatt’s horse at the train station; with Doc’s easy murder of Ed Baily in Prescott; and with Johnny Tyler. We also see it in the way Wyatt deals with Johnny Behan, and later, with most of the Cowboys.

Another of Jarre’s scripted scenes depicts the friendship that warms between Sherman McMasters and Wyatt, and later makes us understand why McMasters joins Wyatt in the aftermath of the O.K. Corral fight. “You seem like a nice fella,” he says to Wyatt. “Like to’ve known you better, had you lived.”

This is where the heart of the picture is—how Doc and Wyatt relate to each other, and how they keep their distance from a world of fools. Doc does so with his elan and ironic world view, and Wyatt with his stoicism and fearlessness.

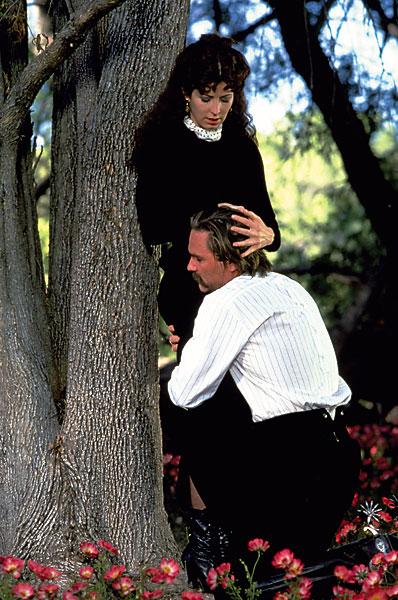

If Russell can be credited with making the set function (as we’ve been told), we should also hold him accountable for chucking parts out of the picture that might have given it greater scope. For instance, the horse-racing scene between Josephine and Wyatt finishes in the script with the sexual encounter that it’s so obviously leading up to.

Jarre’s script does contain a great deal of exposition. Fans of the history would have loved it, but filmmakers, especially those, like Russell, who are schooled in disciplined productions, can’t help but see such expositions as either indulgent or unnecessary. Determining what should be kept or cut is a thorny issue, because the decision can mean the difference between art and commercial success.

As an example of a cut scene, one lovely bit of dialogue leads up to the theater scene early in the film. Tombstone Marshal Fred White (Harry Carey Jr.) is giving Wyatt a run down on the different Cowboys in the audience. “Well, everybody’s here, except the Old Man. Got the blade, Billy Grounds, Zwing Hunt, Billy Claiborne, Wes Fuller, Tom and Frank McLaury. Billy Clanton’s the youngest—wild one. Then the breeds: Hank Swilling, Pony Deal, Florentino’s Mex breed. They all hate Mex, but he hates ’em special. Johnny Barnes, Frank Stillwell. That’s Behan’s little deputy, Billy Breakenridge—follows the Cowboys around like a puppy. And the big boys: Curly Bill Brocius, he’s the Old Man’s ramrod; the one looks like an actor, that’s Johnny Ringo. Best gun alive they say. He’s kinda different. Curly Bill’s the only one he talks to. I mean they’re all rough boys, but Ringo … I don’t know. I really don’t.”

Would a film of Jarre’s entire script have made a cinematic masterpiece out of what is an undeniably first-rate Western? What if Jarre had been given the money and support necessary to complete directing the movie, instead of being fired and removed from the production? These are hard questions to answer, because even though Tombstone was not directed by a master craftsman (Russell or the credited director George Cosmatos), the movie is easily as good or better than most of the movies that Clint Eastwood has directed in his post Sergio Leone/Don Siegel career. Russell deserves more credit than he’s been given for the look and feel of the picture (he should step up finally and take the bow he has coming).

Fans of Jarre’s script are left with the dream that Russell might someday dust off whatever unseen footage he has to create a fuller version of the picture. Then perhaps a producer like Criterion might do for Tombstone what it has done for other classics and near-classics, which would be to give us a visual essay and analysis of the Tombstone that is, and the Tombstone that might have been.

The drama of Tombstone is that of a visionary scriptwriter, Kevin Jarre, who turned in a screenplay that was financially unfilmable, and who may have never recovered completely from the trauma of being removed from the production. It’s classic Hollywood, and it’s a tragedy.

Henry Cabot Beck is the Film Editor for True West, writes about pop culture in general for other publications and is a member of the Phoenix Film Critics Society.

Photo Gallery

This never seen shot has Wyatt (Kurt Russell) and Josephine (Dana Delaney) demonstrating considerably less modesty than in the abridged, final version. From Jarre’s script: “He kisses her again then falls to her knees, throwing his arms around her legs and pressing his face into the folds of her skirts. WYATT: ‘God.…’“

–All Tombstone images courtesy Buena Vista Pictures –