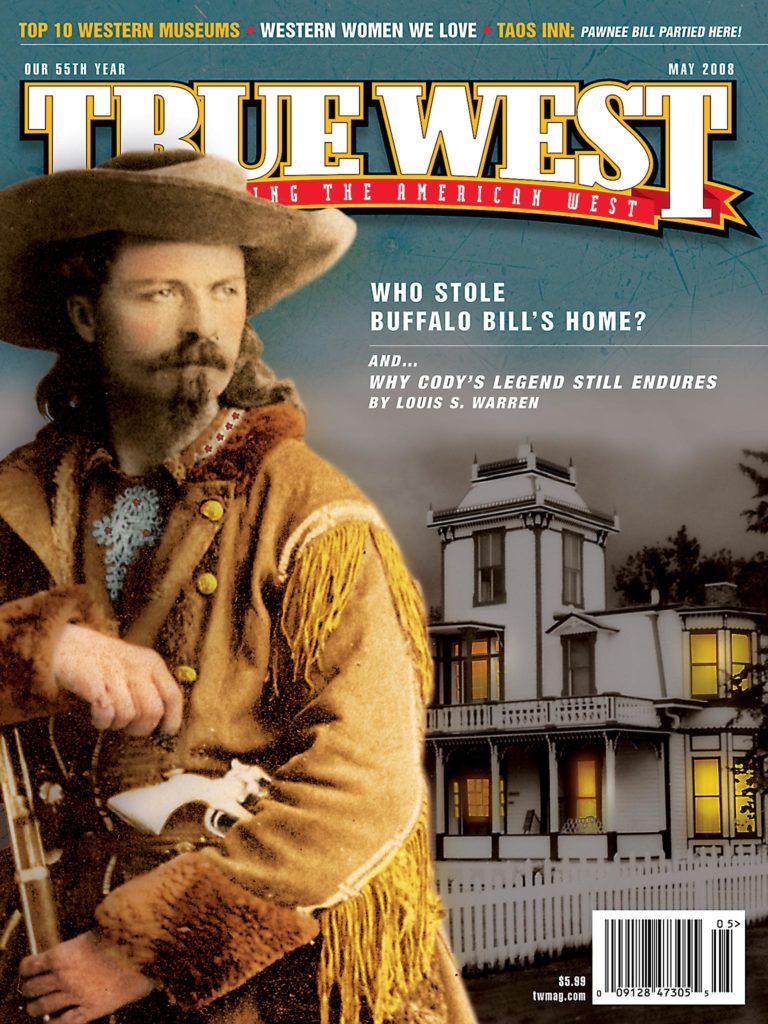

How did Buffalo Bill Cody survive the ravages of time?

He has a prestigious historical center in Cody, Wyoming, named in his honor and is the theme of an entire museum in that center. He’s still the subject of books like Larry McMurtry’s 2005 biography about the colonel and his protégé Annie Oakley. He’s been portrayed in nearly 50 films and TV productions. Even the NFL team in Buffalo, New York, was named for him.

Sorry to correct you, E.E. Cummings, but Buffalo Bill’s not defunct.

He also was not perfect. There’s some truth to Paul Newman’s dark portrayal of Cody’s fame in Robert Altman’s film Buffalo Bill and the Indians in 1976. When you hear news flashes like Troy Lee Gentry from Montgomery Gentry shooting a caged bear or Lynn Anderson accused of shoplifting and driving drunk, it’s natural to think their stars have dropped. Maybe they have; maybe not.

Buffalo Bill certainly knew how to bounce back and spin the media his way. Leading Country and Western musicians, all-knowing “Talking Heads” on the History Channel, rough-riding Rodeo Cowboys, sagacious Poets and Authors, and anyone else who shines (or pales) in the popular eye may want to take a note from Buffalo Bill’s tabloids. His life story reveals how the worldly showman crafted his image to fit his needs, and how that self-crafted image has made him such an enduring legend to this day.

Spur Award-winning author of Buffalo Bill’s America Louis S. Warren shares this inspiring story in honor of the 125th anniversary of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. Was Buffalo Bill a real-life hero, or just one on paper? You’re about to find out.

—The Editors

Was he a hero, or was he a charlatan? Was he real, or was he a fake?

Historians, novelists, poets, artists and filmmakers have been weighing in on that question about William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody since he died in 1917. Throughout the 1950s, Americans saw heroic versions of the Cody story on the silver screen, courtesy of Joel McCrea and Charlton Heston. But if you caught Paul Newman’s Cody in Robert Altman’s film Buffalo Bill and the Indians, you might have been persuaded that Cody was a drunk, a coward, a liar and a con man.

So what was he?

Cody himself would be delighted that we are still asking that question. He reveled in public attention, and he learned at a young age that the best way to stay in the limelight was to stir up an argument about yourself. Whether he was real or a sham was the most common question to swirl around the man even before he appeared in the public eye, and he managed to make a career out of walking the line between truth and fiction, real frontiersman and glam showman, for most of his adult life.

Indeed, his rise to fame was so meteoric that many have concluded that it can only be explained as the product of good publicity, yeasty lies or both. Dime novelist-cum-politician Ned Buntline, on the return leg of a temperance tour to the West Coast, met the 23-year-old Army scout in Nebraska after he had returned from an Army foray against the Cheyenne. Always on the lookout for new material to peddle to editors, Buntline wrote up a highly fictionalized “biography” of Buffalo Bill, “King of the Border Men,” for a cheap story paper, The New York Weekly. The 1869 story—in which William Cody rescues his mother and sisters from the clutches of pro-southern renegades and their Indian allies—was almost entirely hokum. But it created an audience for Buffalo Bill stories, and Buntline duly wrote more.

Dramatized On Stage

Cody’s career continued to develop out West, where Gen. Philip Sheridan persuaded him to accompany him on the widely (and wildly) publicized hunting trip of Russia’s Grand Duke Alexis.

Soon thereafter, Buntline prevailed on Cody to come east in order to star as himself, or at least as some version of himself, in plays that dramatized popular Buffalo Bill novels and newspaper accounts. The show was a dud with the critics, but a hit among the working men who flocked to it in Chicago, St. Louis, New York and many other places.

Before long, Cody had created his own theatrical company, which he toured with for more than a decade. For the most part, he starred in blood-and-thunder melodramas in which he killed scores of red-painted extras or polygamous Mormons on his way to redeeming captive white maidens.

The drama was poor, but it seldom mattered. Cody’s allure was based less on the plays than on the fact that he was not a real actor, but a frontiersman who pretended to act. In this connection, it was to his advantage that theatres operated only in the cooler months. During summers, Cody returned to Nebraska where he revived his frontier credentials, scouting for the Army or guiding well-to-do sportsmen on buffalo hunts.

In 1876, he made a hasty return to the Plains to scout for Gen. Eugene A. Carr’s Fifth Cavalry in the Great Sioux War of that year. While in the field, the regiment received word of Custer’s defeat and death on the banks of the Little Bighorn River. Soon thereafter, Cody rode into a small skirmish. Dressed in a black velvet stage costume with red trim and silver buttons, Cody took the “first scalp for Custer” from a Cheyenne subchief named Yellow Hair (whose name was ever after mistranslated as Yellow Hand). By that fall, he was re-enacting the event for audiences, wearing the same stage costume in which he killed the man.

With its weird mingling of real life and popular fantasy, the stage career provided Cody a good living, but in many ways, it remained beyond the pale of respectability. The plays were too bloody and the theatres too working class to attract middle class audiences whose patronage and respect (to say nothing of dollars) Cody craved. To make matters worse, by the late 1870s, many other scouts had made their way to the stage with competing theatrical companies. John Burwell “Texas Jack” Omohundro, John “Captain Jack” Crawford and a host of now-forgotten others threatened to unseat Cody as the preeminent star of frontier melodrama.

Partly in an effort to shore up his stardom, Cody began hiring genuine Indians for his stage plays. Soon thereafter, he began designing a new kind of entertainment, an outdoor spectacle that would allow Indian horsemen to demonstrate their riding prowess to audiences outside the risqué atmosphere of the theatre. In 1883, he assembled a group of Pawnee Indians and Nebraska cowboys to re-enact frontier warfare and display their riding skills for paying audiences. The Wild West show was born, and for the next 30 years, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West (Cody never called it a show) enthralled audiences across North America and Europe. It became one of the largest traveling shows of that or any era, and it made Cody the most famous American in the world.

Cody’s Real Story

Cody was certainly a real Westerner, but he increasingly leveraged events of his life to make himself more marketable, working hard to fashion a gritty frontier life into a flashy drama. First in his 1879 autobiography, and subsequently with the help of skilled advance men in show publicity, Cody’s life came to mimic the nation’s progress, advancing through “every stage of frontier development.”

His official biography, which was reprinted in many editions and summarized for the press thousands of times, claimed that he spent his boyhood in Kansas, where he grew up a famed Pony Express rider before becoming a celebrated hunting guide who earned the title “Buffalo Bill” by shooting 69 buffalo in one champagne-drenched competition in Kansas. After spying for the Union in the Civil War, Cody alleged, he went on to become a heroic cavalry scout alongside the likes of James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok. He even claimed to have guided George Custer, “whom I always admired as a man and as an officer.”

Not all of these stories were true, a fact that has sometimes reinforced a belief that Cody’s successes were not really his. After all, how could a real pioneer become such a startling success in Eastern show business? Surely, goes this argument, Cody’s fame owes more to his handlers than to him.

Paradoxically, Cody’s actual Western experience taught him many of his first lessons about show business.

His real story was as follows: William Cody was born in Iowa in 1846, when it was still a remote Western state. As a child, his family became one of the first to settle in Kansas, where his father helped to found the town of Grasshopper Falls. He never rode for the Pony Express, but as a boy, he did work for its parent company, the transport firm of Russell, Majors, and Waddell. In contrast to the adventurous rides, hundreds of miles long, that he recounted in the press, his real job was to carry messages on horseback from the firm’s office in Leavenworth to the telegraph station three miles away.

His humble upbringing was an ordinary one in many ways. So, too, was Cody’s young adulthood. The name “Buffalo Bill” was a common one on the Plains, and Cody did not win it in a competition, but by working as a market hunter supplying meat to workers on the Kansas Pacific Railroad in the late 1860s. In subsequent years, he stopped selling meat and mastered the difficult skill of hunting buffalo from horseback to entertain his tourist clients. He was an Army scout, and although he never scouted for Custer—indeed the two men appear to have disliked each other—Cody’s services were sought after by other officers, including Gens. Sheridan and Carr. In hunting and guiding, he was indeed a protégé of an old family friend, Wild Bill Hickok, who appears to have known Cody’s father during the Bleeding Kansas troubles of the 1850s.

How were these two Codys—the frontier ingénue and the savvy showman—embodied by one person? Answering that question requires us to understand how much the frontier West was a place of showmanship and chicanery even before Cody was born.

Frontier Chicanery

The industrial age made advertising and its deceptions part of everybody’s experience. It also shifted the focus of everyday life from familiar rural communities to cities full of strangers. So it was that by the 1840s, Americans especially prized the ability to discern truth from fiction, reality from hoax, a fact that contributed to the rise of P.T. Barnum, whose museum was so much fun because visitors could decide for themselves which exhibits were natural wonders and which were creative fakery.

In some ways, the West as a region had a special relationship to hoaxes. Davy Crockett, Mike Fink and mountain men like Jim Bridger had linked the frontier to entertainment through a kind of verbal hoaxing known as the tall tale. By the time Cody was a young man, the nation’s new railroads furiously extended their lines (they got thousands of acres for every mile they built) as they churned out an ocean of advertising for excellent farm land even while they were crossing parched desert. The West was at least as much hype as substance, and one of the most popular diversions of the age was to figure out which elements of its ongoing tall tale might be true and which were not.

Some Westerners tried to market their skills as guides to newcomers by assuming the poses, language and clothing from the era’s popular dime novels and stage melodramas. Some waited at train stations, dressed in buckskin and bursting with boastful stories to impress tourists and Army officers who disembarked there. For a time, some—notably Martha “Calamity Jane” Cannary and Wild Bill Hickok—turned it into a career.

Cody turned it into an art form. Buntline noticed the young man in 1869, because the scout was already seeking fame. With his long, flowing hair, a flashy outfit and a talent for storytelling, he seemed like he stepped right out of the nation’s frontier fantasy and into reality. From the beginning, he had so many real frontier skills as hunter and fighter, and he so looked the part of a Western hero, that acquaintances wondered if he was too good to be true. Gen. Eugene Carr first encountered the buckskin-clad, beautifully mounted Cody in the autumn of 1868. “There is one of those confounded scouts posing,” he muttered.

The general learned to appreciate Cody’s skills as a tracker and fighter, but Cody continued to push the limits of credibility with his stories, his artful boasts and his considerable skills as a self-promoter. At the height of his superstardom in New York City in 1886, The New York Sun would observe that Cody’s act was so convincing that you could enjoy it even if you did not believe it: “He is a poseur, but he poses impeccably.” Cody’s Western upbringing had taught him that the key to keeping the spotlight on him was to remain at the center of an argument about whether he was real or fake.

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West

The ongoing debate about Cody’s authenticity was central to the attractions of the Wild West show, which mixed many varieties of fact and fakery to service an epic story: the making of American greatness from frontier origins. With real Indians and many real cowboys, herds of bison and elk, and dazzling riding and remarkable sharpshooting from the likes of Annie Oakley and Cody himself (whose signature act was to gallop around the arena, blasting amber balls from the air with a rifle), the show provided a heavy dose of real Western people and animals. Its successes in Europe were a major achievement. It was a hit in London in 1887, and all told, the Wild West traveled Europe for nearly a decade, journeying as far east as Russia and validating American history as a cultural asset.

But for all the authentic Western elements, the show also featured plenty of stardust. Many of the stories told about it were fictional. Annie Oakley, born and raised in Ohio, was no Westerner. Queen Victoria really did visit the show in 1887, but she did not bow to the American flag as Cody’s publicists insisted she had (to the immense delight of the American public).

Some might wonder how much any of this achievement was Cody’s. The story of the Wild West show is so strange that one can be forgiven for thinking that the old plainsman could not have been responsible for it. In truth, managers and publicists did most of the day-to-day handling of poster production, show routes, bookings, payroll and other necessities. But it is also true that Cody reviewed show posters and sent them back for revision when they were not up to standard. He hired show managers and publicists himself. More than that, throughout the life of the Wild West show, he retained creative control over the show’s content and its arena performance. He was, in fact, a demanding arena director, whose temper was hot at rehearsals, even if his language was invariably folksy and clean. “Dog-gone your pictures, cowboy, if you expect to be with this trick very long you better get the lead out of your britches! You move like a man 75 years old!”

As the years went by, and the show grew, the size of this extravaganza also expanded. By the early 1890s, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West had become Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World. In addition to cowboys, Indians and vaqueros, the cast now included black cavalrymen (the renowned “buffalo soldiers” of frontier fame) and new Latin American riders (Argentine gauchos). Also in the mix were European and Asian riders, Russian Cossacks (really Georgian trick riders pretending to be Cossacks) and cavalry contingents from the United States, Britain, France and Germany. In the early 1900s, some Japanese samurai joined.

The performers were only part of the show’s traveling community. Many Lakota Sioux from Pine Ridge, cowboys from Wyoming and vaqueros from Texas and Mexico brought their families along. Added to them were ranks of blacksmiths, wheelwrights, chefs, harness makers, wood choppers, watchmen, drivers, electrical engineers for the traveling generators (the first in show business), razorbacks and roustabouts who unloaded the railroad cars, raised the canvas tents and drove the stakes that pegged them to the earth. By the early 1890s, the show required more than 20,000 yards of canvas and 20 miles of rope, and its community comprised at least 700 people. Three trains moved cast, animals and props from one venue to another, and they often traveled 10,000 miles in a year.

Paradoxically, it was more integrated than any real Western town; and with its novel electrical lighting, it seemed a model of social management and technological progress. Cody and his managing partner Nate Salsbury ordered compulsory smallpox vaccinations and banned alcohol in camp (albeit with limited success). To many observers, this technologically sophisticated, seemingly harmonious, multiracial, healthy, traveling company town seemed a model to which the disorderly, polyglot, industrial cities of the Gilded Age could aspire.

To its performers, it provided a living and a chance to travel. In a sense, this mock-up Old West was a ticket to the New West, as they spent wages on family, livestock, land and equipment at home. Indians, most of them Oglala Lakotas from Pine Ridge, flocked to show auditions because Cody had a reputation for fairness and his wages were better than those on the reservation.

More than this, in an era when Indians were usually forbidden from leaving the reservation, a job with the Wild West show meant free travel and a chance to meet people on both sides of the Atlantic. It was an opportunity for money and adventure and romance. Nicholas Black Elk, accidentally left behind in England when he missed the boat to New York, lived for two years with an English girlfriend. Standing Bear stayed behind to recuperate in a hospital in Vienna, married his nurse, Louise Rieneck, and brought her back to Pine Ridge where they raised a family of their own.

Indians also found a way around the federal ban on dancing at reservations, enforced since the 1880s. Employment with the Wild West meant being paid to dance as well as to ride, and many Indians found the work more familiar and enjoyable than other kinds of labor. When federal authorities investigated conditions in the show in 1890, they suggested that Indians might be better employed elsewhere. “We were raised on horseback,” replied Black Heart, and the Wild West show “furnished us the same work we were raised to.” Some returned year after year, and in many cases, sons and daughters signed up when parents grew too old to travel.

It is not too much to say that Cody’s success with the Wild West show was only possible because of the participation of everyday Western people, especially Indians, a fact he recognized time and again. “My Indians are the principal feature of this show,” he once lectured some recalcitrant cooks, “and they are the one people I will not allow to be misused or neglected.”

125 Years Later

The Wild West show remains in our collective memory as a remarkable community of diverse peoples, traveling the world and performing an American story.

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West was Cody’s premiere achievement. His brief career as a scout with the Army has merited most of the attention of his critics, but it was his career in show business that stands out for his achievements as creator of a remarkable traveling entertainment that became an American institution. Its version of Western history was pure fantasy, to be sure. But in serving as a vehicle for Western peoples to create new paths, and thus new stories for their lives, its achievements were real, and enduring.

Louis S. Warren is the W. Turrentine Jackson Professor of Western U.S. history at the University of California, Davis, and the Spur Award-winning author of Buffalo Bill’s America.