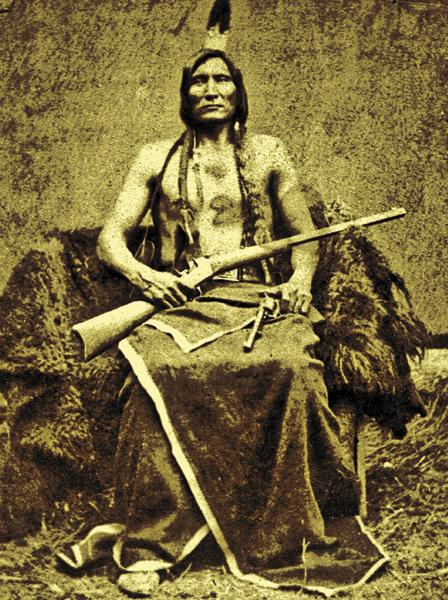

During the Great Sioux War of 1876-1877, Touch The Clouds took his band of Minneconjou Teton followers to the Spotted Tail Agency in northwestern Nebraska. When they arrived on April 14, 1877, the chief rode forward and said, “I lay down this gun, as a token of submission to Gen. Crook, to whom I wish to surrender.”

During the Great Sioux War of 1876-1877, Touch The Clouds took his band of Minneconjou Teton followers to the Spotted Tail Agency in northwestern Nebraska. When they arrived on April 14, 1877, the chief rode forward and said, “I lay down this gun, as a token of submission to Gen. Crook, to whom I wish to surrender.”

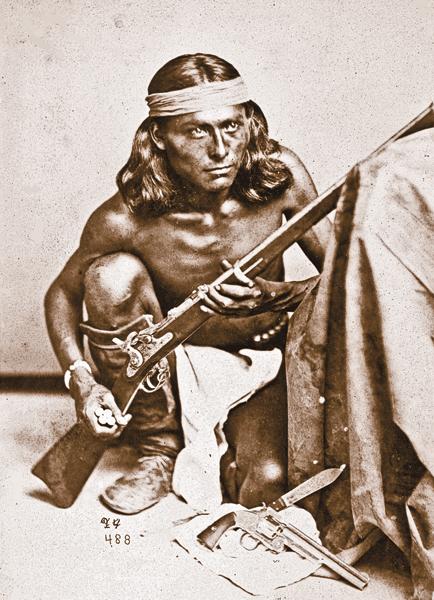

The ferociously strong and brave warrior carried an 1873 Colt Cavalry revolver, as well as a Remington Rolling Block rifle, at the time of his surrender. He may have captured the rifle from a buffalo hide hunter, as rifles of this ilk were generally too expensive for Indians to purchase, and its ammunition could be difficult and costly to obtain.

His story was common among warriors during the Indian Wars. Indians fought white adversaries with guns provided by them, through federally-sanctioned trades, government annuities or as spoils of war. One of the earliest accounts of firearms possession by Indians out West dates to the 1750s, in New Mexico, where French traders cited a brisk exchange of flintlocks to the Wichitas and Comanches for their horses. By the 1804-06 Lewis and Clark expedition, the firearms trade with many Western tribes was already firmly established along the Missouri River.

Firearms, or in some cases the lack of them, played a major role in Indian life from the time they were first introduced to the end of the Indian Wars of the 19th century. Those tribes that possessed both horses and guns were far better equipped to forage for food, wage war or defend themselves than were those who had neither. Together, the horse and the gun combined to make the Indian of the Great Plains the finest light cavalryman the world had ever seen.

From Bows & Arrows to Longarms

Before guns, bows and arrows were the supreme arms of choice, with both hunters and warriors. In skilled hands, bows could be formidable weapons—capable of a fairly rapid rate of fire with reasonable accuracy and range. During the early days of the frontier, Indian bows were equivalent to primitive smoothbore muzzleloaders carried by trappers and traders. Indians also relied on lances, knives and war clubs for weapons. Improvements in firearms made Indians covet them—especially when waging war.

The guns Indians most commonly acquired were European-made smoothbore flint muskets known by several names, but generally referred to as “Northwest Guns,” “Mackinaws,” “fusils” or “fusees.” Early on, Indians preferred British arms over those made by Belgians, the French or Americans. The Indians often obtained these English-made arms by trading with various Hudson’s Bay Company posts, earning these longarms the name “Hudson’s Bay fukes.”

For decades, these Northwest Guns came from British makers who included Barnett, Grice, Ketland and W. Chance & Son. Even the federal Office of Indian Trade purchased fusees from abroad to satisfy Indian preferences.

Distinguishable from other flinters of the era, these trade guns were fitted with a part-octagon and part-round smoothbore barrel that measured from 30 to 48 inches in length. The ruggedly built, lightweight and economically manufactured Northwest Gun could be loaded with either a single ball or a charge of shot. The full-stocked arm employed barrel pins to hold the stock and barrel together in the manner of military muskets. A large sheet iron trigger guard allowed the user to wear mittens while shooting. A brass serpent-shaped side plate opposite the lock became a crucial factor in the sale of these arms, as did other markings, such as a “seated fox,” which signified high quality to an Indian. Those that were a bit better finished, perhaps containing a silver-inlaid nameplate in the stock, were known as “Chief’s Guns.”

Once Indians got a hold of their longarms, they often shortened the barrels, for ease of handling on horseback, one of the Indian warrior’s favorite modes for battle. (At other times, an improperly loaded firearm caused a burst muzzle.) They modified the muskets further by removing the butt plates, in part to keep a sun-heated metal plate from burning the shoulders of these bare-chested braves. Women utilized this thin-edged piece of iron or brass as a hide scraper.

When gun stocks split, forearms burst or wood and metal parts got damaged, Indians wrapped the damaged part with tightly bound wet rawhide, then let it dry so that it shrunk to form an ironclad-like mend. Sometimes they hammered in iron or brass nails to hold together a broken stock, but usually they reserved such hardware to decorate the firearm. Feathers, beads, even human trigger fingers cut from an enemy, as well as other body appendages, could also adorn an Indian’s gun throughout the 19th century.

As the American fur trade grew, so did the Indian gun trade, despite occasional hostilities. While the smoothbore Northwest Guns remained the most typical Indian arm throughout the 1830s, more and more tribes demanded rifled longarms. With more frequent contact with trappers and explorers, some Indians began to learn the basics of rifle shooting and slowly adopted the ways of experienced white hunters and soldiers.

American rifle makers quickly recognized this growing market for their products. Gunmakers such as Henry Deringer, H. Leman, J. Henry, Jacob Forney and the Tryon brothers of Philadelphia led the way with their flintlock, and later percussion, rifles. These Eastern firms filled many of the government contracts for Indian trade guns in the early West.

For some time after the appearance of the percussion ignition system in the 1820s, Indians, like many white frontiersmen, clung to the more familiar flintlocks—partially because of the availability of new flints, as compared to the percussion caps in the early years of the caplock system. For example, after receiving a delivery of 550 percussion rifles in a trade, the Choctaw tribe in Fort Smith, Arkansas, exchanged 200 of them for flintlocks. In another instance, a band of Osages refused percussion arms in 1840, not only because of an abundant supply of flint stones, but also because of a gunsmith, made available to them by the U.S. government, who kept their firearms in good working order.

Whether flint or caplock, Indian trade guns of this period were usually full-stocked arms of .45 caliber or larger. In 1837, the War Department’s Office of Indian Affairs issued specifications for guns destined for trade with various tribes. Built to the standard of measurement at the time, these contracted guns employed a round lead ball in a caliber that “a pound of lead” would “not make less than forty-five, nor more than one hundred, and must be of a length and weight corresponding properly with the size of the ball.”

Although these Indian trade guns—and even the Northwest Guns—remained popular well into the 1870s, firearms turned out for the civilian market, such as the half-stock Plains rifles from fine makers such as Horace Dimick and Samuel Hawken, were also prized by the tribes. But since these firearms carried a much higher price tag, they were less commonly found among Indians. The Utes in Colorado had well-made firearms when frontiersman J.S. Campion crossed their path in the late 1860s. He observed “nearly every man having his Hawken’s rifle, Colt’s revolver, knife, tomahawk, bow and arrows, and lasso.”

When breechloading firearms came on the scene, they spelled the demise of the muzzleloaders among Indian warriors. Such older models were not nearly as effective as these newer and faster-shooting breechloading weapons, which were ideally suited to the Indian’s preferred way of hit-and-run fighting from horseback.

By the end of the Civil War, successful percussion cartridge and metallic cartridge firearms were becoming available in greater numbers on the frontier, and Indians were eager customers, as they began feeling the effects of the Westward migration. The period from the mid-1860s through the late 1870s was one of the most difficult times for our first Americans. The tracks of the ever-increasing stream of emigrants from the East were covering the ancient buffalo trails forever. The Indian was being coerced to live according to white custom, in agricultural reservations, rather than to live the free, nomadic lives of hunters and warriors, an existence they had relished for centuries.

To add to their discontent, they were constantly faced with transgressions of their sacred lands and broken treaties. With each new violation, their reservation boundaries shrunk, the wild game became scarcer and Indians became dependent on a largely uncaring government.

This was also the new era of metallic cartridge and repeating firearms, guns like the Henry and Spencer repeaters, 1866 and 1873 Winchester lever actions, the famed Sharps single-shot buffalo guns, U.S. Army Springfield Trapdoors, Colt and Smith & Wesson six-shooters, Remington rifles and revolvers, Ballard rifles and a slew of other practical longarms and handguns that employed the new self-contained, metal-cased ammunition. Through trade, whether sanctioned by the government or illicit, Indians received firearms as battle trophies or as gifts presented as part of annuity payments, new treaties or redrawn reservation boundaries.

Ammunition became a problem tribes had not faced during the days of muzzleloading firearms. As long as a warrior had powder and lead, a few flints or percussion caps, he could rely on his firearm. He could even pound out a projectile by hand, to the appropriate shape and size of the gun’s bore, and then use a scrap piece of cloth, buckskin or other material suitable for patching to keep his firearm ready for battle.

This crude method of charging a muzzleloader did not bother the Indians because marksmanship was not one of their strong points at that time. Indians didn’t fully understand the use of sights or the measurement of distances. As Gen. Nelson Miles, a veteran of many frontier campaigns, put it,”The typical Indian is a point-blank marksman. The use of bright muzzle and buckhorn sights proves this. He steals upon his quarry and fires at it.”

Indians filed the sights flush with the top of the barrel, or they completely removed them from the rifles. They didn’t understand the long-range tang sights either, and they usually discarded them.

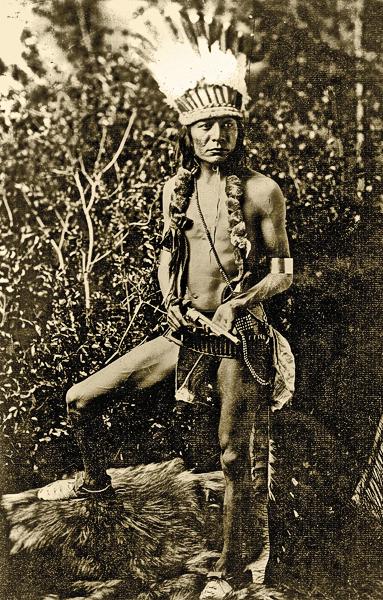

Much of the Indians’ ways of engaging in combat did not require sophisticated sights. They were expert horsemen and generally relied on snap, or point, shooting. One of the favorite ways of attack by a young buck from one of the Plains tribes was to charge in close to the enemy while hanging from the side of his pony, using his mount’s body as a shield. Then one of his hands took quick aim, and he fired the rifle or handgun from across the saddle, over or even under the horse’s neck. Although this method may not have provided the warrior with the best accuracy, it certainly impressed his more “civilized” white enemy, while making the rider a more difficult target.

When Indians were able to obtain fixed ammunition, they often paid exorbitant prices. Many reported incidents document Indians purchasing or trading for cartridges at greatly inflated selling prices. One such incident occurred in 1870 at Fort Berthold, Dakota Territory, when a lone Indian made a futile effort to trade three ponies for a box of about 50 cartridges. In many instances, frontier Army officer Col. Richard I. Dodge watched Indians offer one well-tanned buffalo robe for just three cartridges!

To help overcome a shortage of ammunition, an Indian utilized some inventive methods of keeping himself supplied with serviceable, reloaded cartridges for many firearms. Col. Dodge commented, “…if he can only procure the moulds for a bullet that will fit his rifle, he manages the rest by an ingenious method of reloading his old shells peculiar to himself. He buys from the trader a box of the smallest percussion caps, and…forces the cap in [to the shell] until it is flush. Powder and lead can always be obtained from the traders; or, in default of these, cartridges of other calibre are broken up and the materials used in reloading his shells. Indians say that the shells thus reloaded are nearly as good as the original cartridges, and that the shells are frequently reloaded forty or fifty times.”

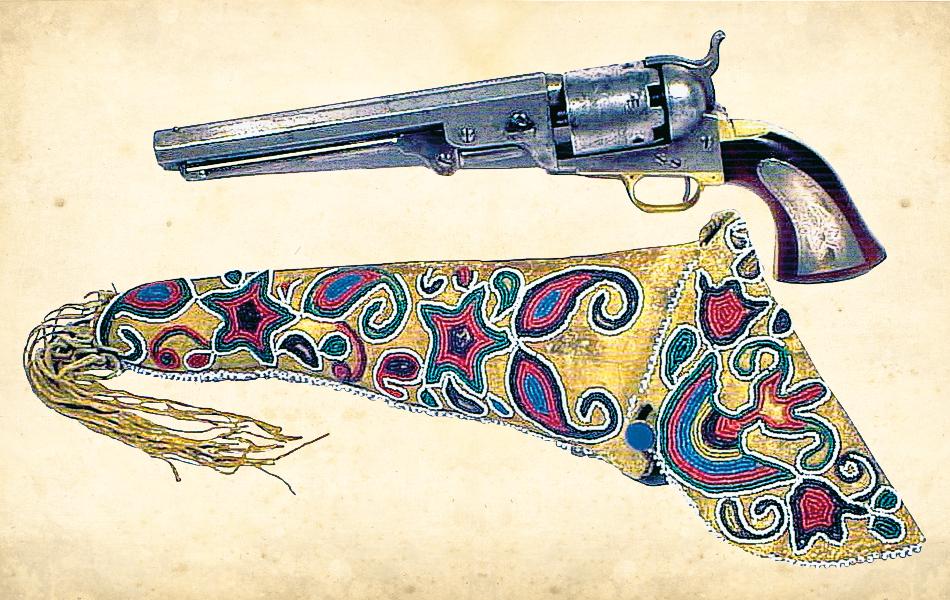

For buffalo hunting as well as for battle, Indians often favored the less cumbersome handguns. Virtually any handgun—from single-shot Kentucky-style Hawken and military horse pistols, to revolvers, including pepperboxes, Colt’s, Remington’s and other manufacturers’ caplock and cartridge six-shooters—could be found in an Indian’s possession. As with the shoulder arms, many of these were purchased through official sources too. Through the years, historians have turned up several authenticated Indian-owned handguns that, like their long guns, had been embellished with tacks, rawhide strips and other available materials.

As eager as an Indian warrior might have been to lay his hands on a modern metallic cartridge gun, the older muzzleloaders fought alongside the most up-to-date armament in the futile struggle for the Indian’s disappearing way of life, until the last battles of the Indian Wars. Time and again, military inventories of captured Indian weapons revealed their firepower generally consisted of flintlocks, percussion arms and repeating metallic cartridge shoulder arms and handguns, not to mention the bows and arrows of those unable to procure a firearm.

Despite the heroic struggles and strong resistance the Indian warrior offered his white foes, enemy tribes, Indian military scouts and others hostile to him, at best he could only fight a slow retreat. Even with the prominence of the most modern repeating rifles in many of these historic confrontations, like the Sioux and Cheyennes’ Battle of the Little Big Horn in 1876, Dull Knife’s Cheyennes’ valiant 1878 trek in an attempt to return to their homelands and the campaign against Geronimo and his Chiricahua Apaches in 1886, Indians had little chance of turning the tide of the white man’s domination of the West.

With the Indian belief that the true warrior’s place is to protect his people, he stubbornly fought on, greatly outnumbered and technologically overmatched. Having been hurtled from the Stone Age into the Industrial Age in just a couple of generations, the wild, free nomad of the Plains was pushed to the brink of annihilation. Indians ultimately laid down their arms and accepted the white man’s rule.

But in the end, frontier Indian warriors often left their people, and all Americans, with a legacy of pride, bravery and ingenuity in their use of armaments alien to their culture. In war, each was a fierce and resourceful fighter. In peace, the Indians of today walk proudly among us—our first Americans!

Phil Spangenberger has written for Guns & Ammo, appears on the History Channel and other documentary networks, produces Wild West shows, is a Hollywood gun coach and character actor, and is True West’s Firearms Editor.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Glen Swanson Collection –

– Courtesy Glen Swanson Collection –

– Courtesy Bob Coronato/Rogues Gallery –

– Courtesy Bob Coronato/Rogues Gallery –

– Courtesy Glen Swanson Collection –

– Courtesy Glen Swanson Collection –

– By Chris Sowin / Courtesy Denny Foreman Collection –

– Courtesy Glen Swanson Collection –

– Courtesy Glen Swanson Collection –

– Courtesy Phil Spangenberger Collection –