“It is the easiest thing in the world to make a living here if a man is industrious; but I am more and more hopeless of our ever making enough money over farming here to come home again. It is the old story—want of capital. No one out here expects to be rich; one can make a living, but nothing more,” wrote Ethel Hertslet, who arrived in Lake County, California, in 1885 from England.

“It is the easiest thing in the world to make a living here if a man is industrious; but I am more and more hopeless of our ever making enough money over farming here to come home again. It is the old story—want of capital. No one out here expects to be rich; one can make a living, but nothing more,” wrote Ethel Hertslet, who arrived in Lake County, California, in 1885 from England.

What possessed people like Ethel to begin a new life in a foreign land? It’s called the American West, where anyone can reinvent himself and the starry Western sky is the only limit. Well, that, a lot of hard work and some luck.

Despite not having any plans or manual labor experience, Ethel and her husband, Gerald, felt the great American frontier could be their salvation. They needed something after Gerald and his brother Louis were nearly bankrupted when the Egyptian market, where they were heavily invested, crashed due to Egyptian civil unrest in 1884.

Even though Gerald and Louis were strapped for cash, their well-to-do father, Sir Edward Hertslet, was not. When they, along with another brother, Bernard, set sail for America, Sir Edward sent a thousand pounds ($118,000) with each of his sons. Ethel also received a yearly allowance of $500 ($12,100) from her parents.

Not only were the Hertslet brothers beginning a new chapter in their lives, so were Ethel and Gerald. After a brief courtship, they had wed, against Sir Edward’s wishes, just eight days before departing for America. Ethel was from a musical family, albeit wealthy, and was reportedly an actress, but she was hardly a social match for the son of a knighted Englishman.

They arrived in California on May 6, 1885, and checked in to the lavish seven-story Palace Hotel in San Francisco at the corner of Market and New Montgomery Streets. Opened in October 1875, the Palace was allegedly the largest, costliest and most luxurious hotel in the world. It cost an outrageous $5 million ($117 million) to complete and featured 755 rooms sized at 20 square foot with 15-foot ceilings. Guests could enjoy views of the city from 7,000 windows in this majestic hotel hailed the “Grande Dame of the West.”

Ethel and her companions entered the hotel through a graveled carriage entrance. They marveled at balconied galleries and white marble columns in the Grand Central Court as they walked beneath a lofty roof made of opaque glass. Even though Gerald and his new bride reveled in this opulence, sensibility had them checking out just two days later.

They eventually made their way north to Lake County where they bought 80 acres and built a ranch. These pampered English were happy to find others like themselves in an area called Burns Valley, near Lower Lake. English citizens in “their class” or “well-connected,” as Ethel wrote, resided in Burns Valley.

The community was largely populated by British aristocracy who practiced what they referred to as “fancy farming,” reported The San Francisco Chronicle. John Beresford, the Marquis of Waterford’s nephew, was just one of the distinguished men living there.

At first the Hertslets struggled with what to plant or raise once their ranch was built. They initially wanted to plant grape vines since the area seemed so right for it, but the prohibitive cost of fencing led them to raise chickens with the intention of cornering the local market. In 1885 Gerald wrote, “I am afraid we shall not be able to plant much this year, because of the expense of fencing, so we are going in for a chicken-ranch, which, as far as it goes, is very paying, and will enable us to go on with our improvements out of the profits.”

They slowly added fencing and began to plant grape vines and fruit and olive trees. Their hard work showed signs of progress, and their peach and plum trees were budding light pink flowers, as were their 130 grape vines. While they were seeing progress with their plantings, they weren’t doing too well with their chicken farming. Gerald and his brothers’ mistreatment and poor care of the chickens led to their demise. Lack of water irrigation also led to the end of the fruit and tree plantings. Ranching did not seem to be their forte.

Within a few years, the Hertslets were no closer to gaining back their lost fortune, and their prospects looked dim. A clue as to why their farming efforts failed appeared in the Chronicle, “[Burns Valley] laborers were sons or nephews of titled Englishmen and the colony lived in luxurious style, yachting, having private theatricals, playing cricket and occasionally farming.”

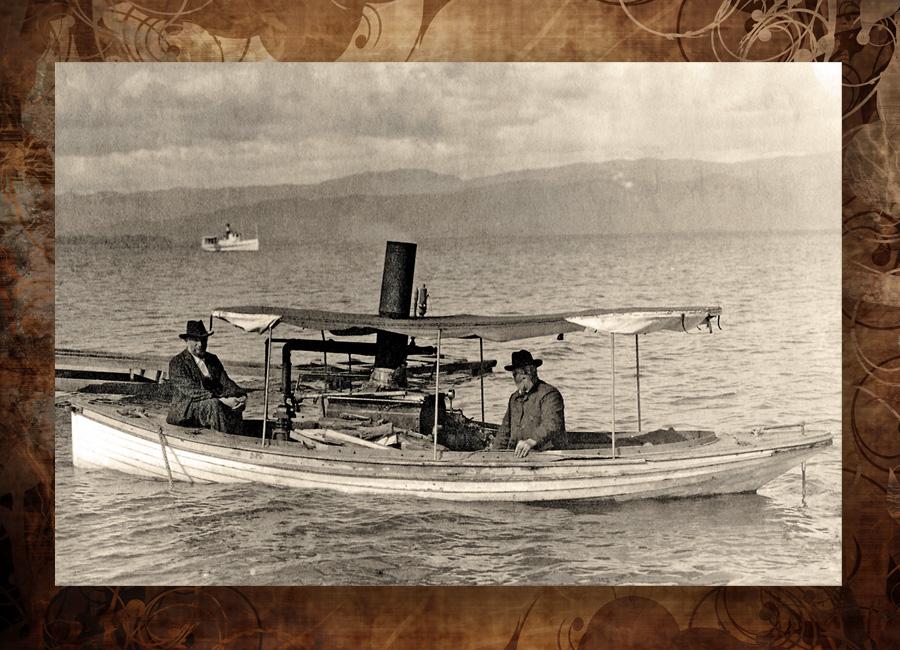

The report was true; Gerald and others often sailed on Clear Lake, and they frequently went on drinking “convivials” at nearby Cache Creek. Gerald was especially known for mixing a mean cocktail, reported the Chronicle, and was renowned for his gin fizzes and Russian cocktails.

Gerald and his friend Thomas Beakbane owned a small boat together and sailed it often on Clear Lake. It was an open, wooden boat with a top, typical of others on the lake, but this boat had a peculiar twist. Even though having a wood burning steam engine wasn’t uncommon, theirs afforded a slight oddity. Having an engine was a good idea, but having it, the boiler and the necessary firewood in the center of the boat was not. If they wanted to get from one end of the boat to the other, they had to dock, get out onto the wharf and then change places.

When the two friends weren’t sailing, they could be found playing cricket for the Burns Valley team, which first formed in 1887. The cricket matches were known throughout the valley, as were the parties that followed. It’s not surprising these fancy farmers took up the traditional sport they played back in England.

Tales of cricket playing, boating, lazy ranching habits and an overall good time were conjured up whenever the Hertslet name came up, according to newspaper reports. These English squires reportedly did not rise at 5 a.m. like the traditional farmer, but slept in and only milked their bovines after they had breakfasted. The youngest Hertslet brother, Godfrey, who did not go to California, later wrote, “…they must have had a pretty good time while the money [supplied by father] lasted.”

By 1887, Gerald’s brothers had returned to England and Ethel’s three cousins, Claude, Ernest and Guy, arrived to help. By that time though, Gerald had sensibly given up ranching and became a real estate investor with Beakbane. Ethel’s cousin Claude Barry bought his own land from Beakbane and the Hertslets, and he married Ethel’s domestic help, Edith Forster.

Just five short years later, Gerald and Ethel were parents of three children and had sold their ranch and taken up stage careers in San Francisco. The Barrys also moved to San Francisco where Claude became an accountant. Gerald and Ethel toured California, Nevada and Washington before they bankrupted in Nevada City, California, in March 1894.

In July that same year, Gerald received an unusual telegram with first-class passage back to England to perform in a play, and he left alone. Ethel remained in San Francisco, but she quickly slapped him with a divorce for desertion. He counter-sued, and their nasty, publicized divorce came to an ugly end in a New York City court in 1898.

Almost simultaneously with Ethel’s divorce filing, her cousin Claude filed his own. In October 1894 Claude filed for divorce against his estranged wife, Edith, after only six years of marriage. He cited her with cruelty based on the fact that she was a morphine fiend with habitual intemperance. Edith denied the charges and filed a cross-complaint against Claude, charging him with adultery. Claude also noted that a year earlier Edith had tried to stab him with a knife while she was under the influence. But, being larger than his stoned wife, he was able to fight her off. In 1898 the San Francisco Call interviewed Edith, quoting her as saying, “Through Claude Barry’s negligence I have been sick nigh unto death (having spent seven weeks in the hospital), with the barest necessities of life as my portion, and I can but bitterly denounce the duplicity of a man who had promised to care for me in life.”

Oh, how Victorian!

After his failed theatre performance in London, Gerald did not return to America. It seems that both Gerald and Edith, who had accused Ethel and Claude of infidelity, were right. By 1897 Ethel had moved to New York City to live with her first cousin Claude. They eventually married, but only after Gerald died in 1918. Ethel finally got her wish to return home to England in 1932.

All things are relative, right? In Ethel’s mind, they were poor, isolated, and living a pioneer life. But if she actually

stopped to think about others around her, she may have realized she was far better off than most who went west. Really—how many poor pioneer women had servants on their ranch? Then again, how else could she feel? She only knew her English socialite world where she was raised. Considering all she experienced and witnessed, she likely felt like a victim. In the end, she made her own fateful decisions.

You’ll be able to read Sherry Monahan’s Hertslet story in Her Fateful Decisions: The True Story of Ethel Hertslet, a book currently pending publication. A people and food genealogist, she is also the winner of a Wrangler Award for the History Channel’s “Cowboys & Outlaws: The Real Wyatt Earp.” Visit SherryMonahan.com to learn more.

Photo Gallery

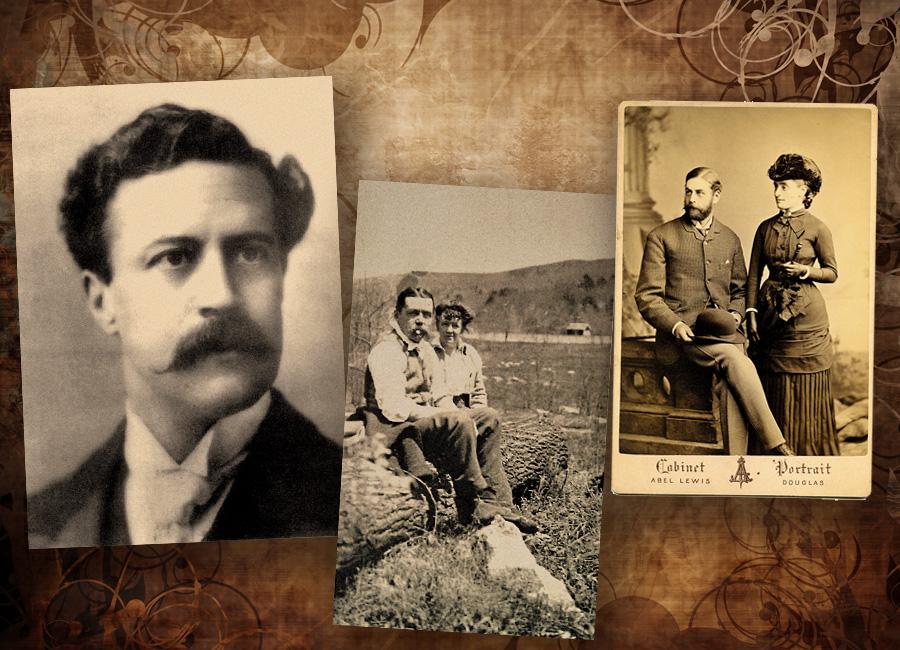

Gerald Spencer Hertslet was born January 6, 1859, in Richmond, Surrey County, England. He was the fifth of nine children born to Sir Edward Hertslet, the librarian of the Foreign Office at Westminster. Gerald’s mother was Lady Eden Bull Hertslet. Gerald died in 1918 at the age of 53.– Courtesy Sheila Hertslet Hodges –

Claude and Ethel, circa 1900s:Claude Barry (center) was 22 when he arrived in Lake County. He was born in Rochester, England, on June 2, 1862, was five foot five and had brown eyes. Ethel Marion Barry-Hertslet was born April 20, 1864, in Putney, Wandsworth, Middlesex County, England to Edith Bird and Charles Ainslie Barry, who was a noted composer and musician during his time. After her divorce from Gerald, Ethel and her cousin Claude resided in New York City. Claude was an accountant, and Ethel became an actress who played Broadway and traveled the Victorian theatre circuit.– Courtesy Elizabeth Bull –

Thomas and Margaret Beakbane, circa 1870s:Thomas W. Beakbane and wife Margaret (right) were English-born and were the closest friends of Gerald and Ethel. After the Hertslets left Lake County, Thomas went on to do many things in the area. In June 1900, he was still farming in the Lower Lake area with his wife and their two little girls, Margaret and Manzanita.– Courtesy Patricia Allen Sparacino –

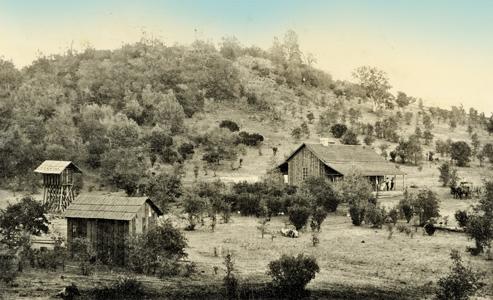

The Hertslets bought 80 acres in 1885 and built a clapboard wooden structure whose total cost would be $450 ($10,900). It was 44 feet long and 18 feet wide with a 46-foot-long veranda and a California redwood shingle roof. It also offered indoor running water near the kitchen and in the bath, which led from a pipe at the well to a tank inside the house from an 1,800-gallon, 10-foot outdoor water tank. The barn, the chicken house, the pump, tank and pipe to the house cost about $105 ($2,530). The barn also had pipes from the well, so it had water too.– Courtesy Patricia Allen Sparacino –