In his 1986 book Deadwood, Pete Dexter depicted Wild Bill Hickok as suffering from some form of venereal disease (VD) and more so from the remedies of the day.

In his 1986 book Deadwood, Pete Dexter depicted Wild Bill Hickok as suffering from some form of venereal disease (VD) and more so from the remedies of the day.

The historical accuracy of Bill’s condition was probably fictional. Dexter’s depiction of Bill’s misery, however, can help us examine the true nature of VD in the Old West, and how these disorders were managed medically in the days before antibiotics and modern diagnostic methods.

Gonorrhea or Chlamydia Jane?

Dexter depicted Bill as having a “blood disease” that affected his urinary tract, which would probably mean he had either gonorrhea or a chlamydia infection.

In the novel, Charley Utter, Bill’s traveling companion, said he believed that Bill’s diminishing eyesight and his difficulty passing urine (spending 30 minutes in the bush) were not separate problems.

From today’s medical perspective, Charley may have been on to something. Chlamydia was then and is now one of the leading causes not only of urinary tract problems but also of blindness.

Dexter, however, attributed Bill’s problem to glaucoma, a condition in which elevated pressure inside the eye causes damage to the optic nerve, which, if left untreated, may lead to blindness. If glaucoma was the cause, Bill probably would have had gonorrhea.

Poisoning and Other Tortures

Bill was confronted by the unfortunate medical reality that the “cure is often worse than the disease.” Dr. Wedelstaedt, a specialist in “diseases of passion,” prescribed the mercury treatment for Bill.

Dexter described Bill’s condition through the eyes of Charley Utter: Bill was “… sitting on the stump he favored, rubbing himself with mercury. If Captain Jack noticed Bill had silver skin, he didn’t say so.”

“Bill came out of the bushes, drooling blood. Charley saw clearly that the disease had taken his strength, and didn’t have any left inside himself he could borrow against.”

Bill had been “…drooling in his sleep from the poison of mercury. Charley had seen the mercury cure before; the next step, Bill’s teeth would loosen.”

By the 1870s, mercury compounds had been used to treat gonorrhea and syphilis for at least a century. (Chlamydia infection as a cause of VD had not yet been recognized.) Patients received mercury in myriad ways, from inhalation and ingestion to skin applications and even intravenous injection.

Bill frequently rubbed what was probably highly soluble (hence, quite toxic) mercuric chloride on his skin. Without accurate control of the dose, patients would develop signs of mercury poisoning: excessive salivation, bleeding gums, loosening of teeth, a silver or grayish discoloration of the skin, a hand tremor and even madness.

Interestingly, mercury-induced madness has been immortalized by the character of the Mad Hatter, from Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland (1865). The Hatter exhibited the not-so-uncommon problem of “insanity” in hat makers who used mercuric nitrate to smooth animal fur, separated from pelts, while making their hats.

In a further effort to manage his disease, Bill suffered another hideous treatment. Bill said of his doc: “He’s got treatments, but nothing that would appear to be better than dying. One thing is a wire that he sticks up your weasel and heats it.”

Doc Wedelstaedt would have roasted Bill’s urethra, a tube that carries urine from the bladder through his penis to the outside world. Historically, other VD treatments included injecting mercury compounds into the urethra by syringe. In 1803, members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition carried calomel (mercurous chloride) and four penile syringes, just for this purpose.

A Passionate Problem

More than half and sometimes as many as 90 percent of prostitutes on the frontier were believed to have been infected with gonorrhea or syphilis; and 64 to 80 percent of men with gonorrhea contracted it from these “ladies of the night.”

In 1913, C.C. Norris, MD, reported that the overall rate of venereal infection in the U.S. army between 1876 and 1895 was about 83 cases per 1,000 soldiers.

Many cases of VD back then, as today, were asymptomatic. About 30 to 70 percent of infected men and women did not know they were infected. This ignorance facilitated the spread of VD, especially in brothels.

In the 1870s, any cowboy who availed himself the services of a “soiled dove” risked contracting misery and pain as the reward for his hour of fun.

Quackery

Dexter depicted Bill, with steady hand, shooting shot glasses off the head of Pink Bufford’s bulldog. Bill did not exhibit a “mercury tremor” that possibly would have affected his hand while he held and used his pistol. Although quite eccentric, Bill also showed no signs of madness, another likely symptom of mercury poisoning.

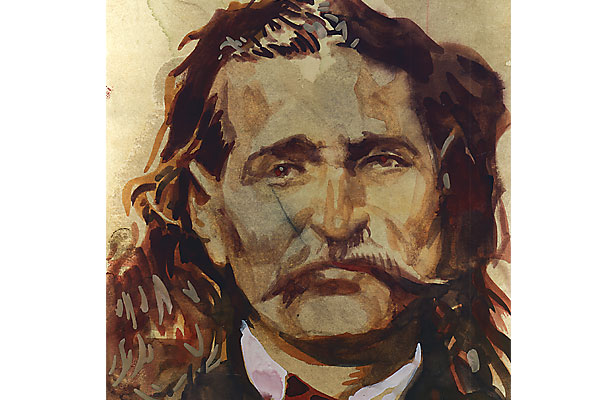

Thus, in Dexter’s book, although Bill exhibited pain, he lost neither his brain, nor his aim, until Jack McCall assassinated him in Deadwood, South Dakota, on August 2, 1876.