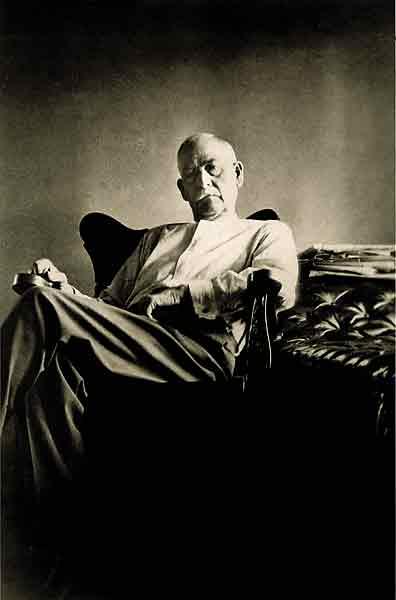

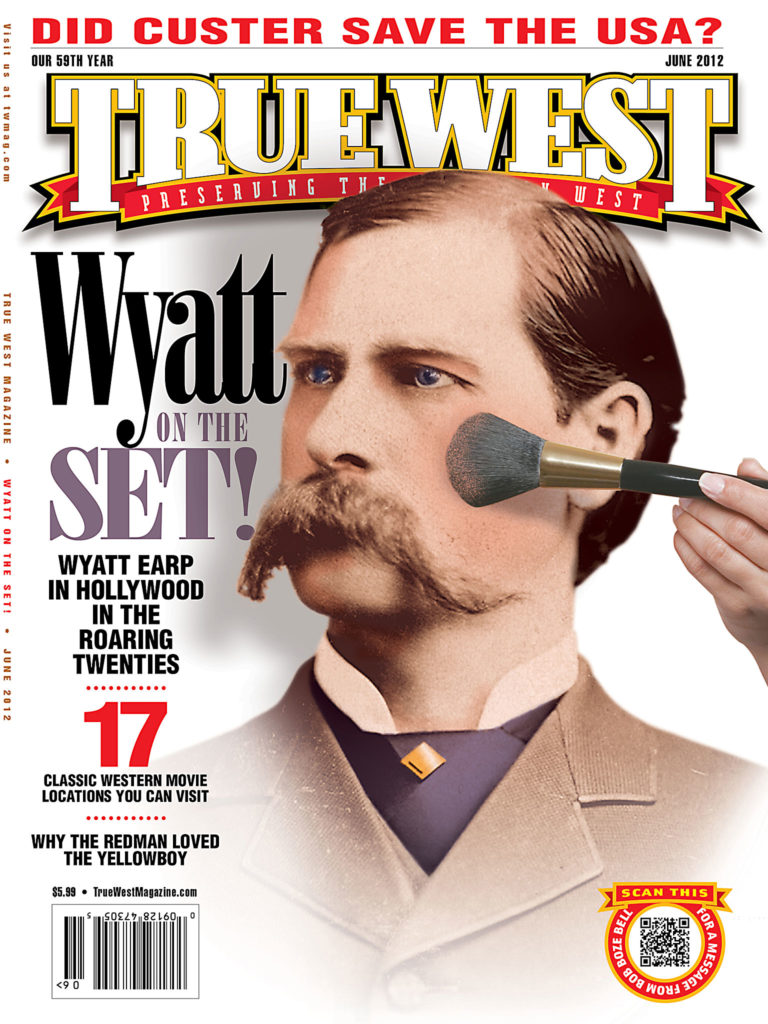

His story, said Bat Masterson, was the story of the West. For years Wyatt Earp was reluctant to tell it. But as some began to resurrect his mythical past, Earp saw his name tarnished and his life exploited. In his old age, he wanted to bring his story to the screen—he knew the biggest names in movies, stars like William S. Hart, Tom Mix and Harry Carey, and America’s greatest writer, Jack London. His story would come to dominate Western movies, but things didn’t quite work out as he hoped..

His story, said Bat Masterson, was the story of the West. For years Wyatt Earp was reluctant to tell it. But as some began to resurrect his mythical past, Earp saw his name tarnished and his life exploited. In his old age, he wanted to bring his story to the screen—he knew the biggest names in movies, stars like William S. Hart, Tom Mix and Harry Carey, and America’s greatest writer, Jack London. His story would come to dominate Western movies, but things didn’t quite work out as he hoped..

On a sunny day in 1916 Raoul Walsh—the one-time cowboy, sailor and movie actor-turned-film director—was taking it easy between studio shots at the Mutual Film conglomerate in Edendale, California. (Angelinos today know the area as Echo Park and Silver Lake.) An assistant told Walsh that two guys at the studio gate were asking for him. “One says his name is London.” Walsh told the assistant that if his first name was Jack, “bring them in.”

That’s how Raoul Walsh met Wyatt Earp and America’s then-greatest living writer, Jack London. The two had known each other in Alaska and decided one day to seek out the man who had gone to Mexico to work with Pancho Villa on his own screen biography.

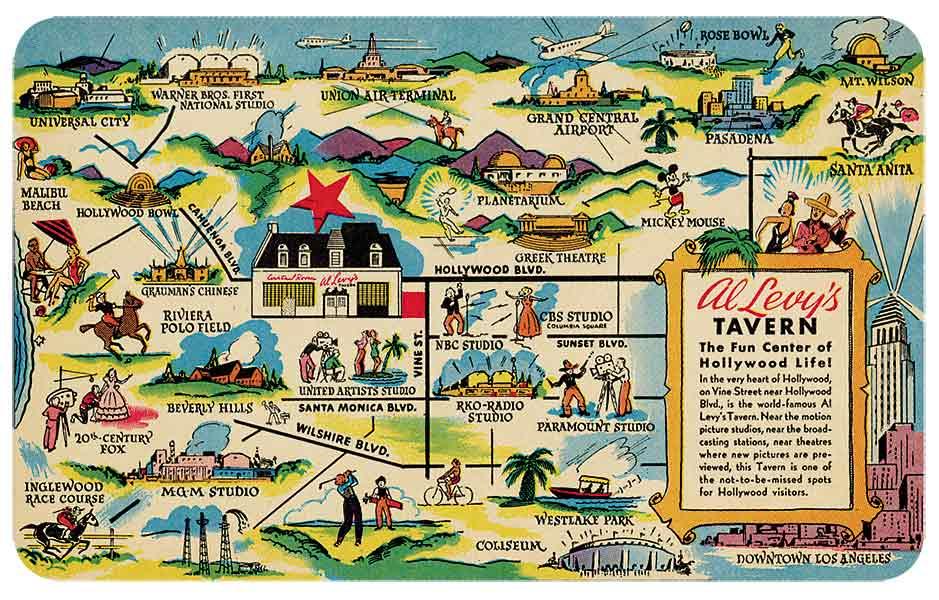

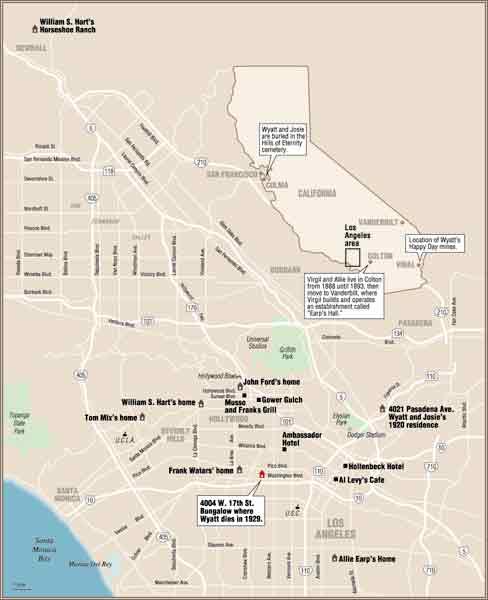

Walsh took his distinguished guests to dinner. In 1916 Hollywood was still mostly a name on a map with most of its famous restaurants still to come. The trio went to Al Levy’s Cafe on Main and Third Street. While enjoying Levy’s famous oyster cocktails, Walsh’s table was visited by the highest paid entertainer in the world, Charlie Chaplin. Chaplin was in evident awe of both men, but particularly the former deputy marshal of Tombstone. Walsh remembered Chaplin saying to Earp, “You’re the bloke from Arizona, aren’t you? Tamed the baddies, huh?” This chance encounter between Earp and Chaplin provided the inspiration for the 1988 Blake Edwards film, Sunset.

Earp was far from famous in 1916 and had little visible means of support. For years his activities had skirted both sides of the law; in 1911 he had been arrested for his part in a “bunco game.” This was about the same time that Earp was working on special missions for the Los Angeles Police Department, as reported by former police officer Arthur King. All the while, Wyatt mixed with old-time Westerners who had settled in southern California and whose adventures, like his own, were being cleaned up for two-reel Westerns.

Most product in this period was produced by companies connected with Universal, headed by legendary mogul Carl Laemmle. It seemed like everyone was forming production companies. As film pioneer Lewis J. Selznick remarked in 1917, “it takes less brains to make money in pictures than in any other business.”

“The bulk of Laemmle’s operation would always be cheap bread-and-butter movies” wrote film historian Scott Eyman, and in the 1910s and 1920s, this meant Westerns.

Earp’s connections to this world are shadowy. We don’t know how he came to be on the set of director Allan Dwan’s Douglas Fairbanks vehicle, The Half-Breed, in 1915. In his autobiography, Dwan recalled, “He was a visitor to the set when I was directing Douglas Fairbanks in The Half-Breed. As was the custom in those days, he [Earp] was invited to join the party and mingle with our background action.”

Earp, said Dwan, was “a one-eyed old man” who “had been a real marshal in Tombstone, Arizona” and “was as crooked as a three-dollar bill. He and his brothers were racketeers, all of them. They shook people down; they did everything they could to get dough.”

Exactly who Dwan was recalling isn’t clear; at age 67, Earp was indeed elderly, but still tall and standing straight, and he certainly had the use of both eyes. Researcher Jeff Morey has speculated that the man Dwan may have been thinking of was one-time sheriff of Cochise County, “Texas John” Slaughter.

Dwan also recalled that Earp, after watching Fairbanks jump from tree to tree, declared acting was not for him. “Oh, no,” Earp supposedly said, “I’d not like to do that.”

Did Earp have any movie ambitions? He certainly had enough pals among the Western stars of the silent era. His first connection may well have been his old colleague on the Dodge City police force, Bill Tilghman, who, in 1915, managed to get backing for a project based on his own exploits, The Passing of the Oklahoma Outlaws, which he directed and starred in.

In 1920, Tilghman came to Los Angeles seeking Universal’s backing for another film and dropped by to see Earp. One wonders if the two former peace officers considered a dual project on their time in Dodge City, Kansas—perhaps even a collaboration with their old friend Bat Masterson, a well-known newspaperman in New York.

Among Wyatt’s amigos were the biggest Western film stars of the era, including William S. Hart, described by film historian David Thomson as “one of those Americans who stepped from the actual West into the cinematic version of it.”

Born in Newburgh, New York, in 1865 (some sources state 1870), Hart had been on a cattle drive while in his late teens and had exercised horses for a riding school. After 1888, though, and for the next 24 years, he was a stage actor in New York; his biggest success was not, as press agents would later maintain, in Shakespeare, but in an enormous Broadway production of Ben Hur.

Hart was already middle-aged when he joined his friend Thomas Ince at Ince’s studios in 1914 for a series of immensely successful two-reeler horse operas, many shot in New Mexico and Arizona, but beefed up with location shots in the San Fernando Valley. He was the Gary Cooper of his generation (Cooper, like Hart, would also play Wild Bill Hickok).

Hart was a stickler for realism, and his heroes were known for their stern moral character. It’s likely that Hart slipped Earp a few dollars for some on-set advice on costume and dialogue. Earp was one of the characters portrayed in Hart’s 1923 epic, Wild Bill Hickok (see p. 36), but we don’t know what Earp and Masterson and Doc Holliday were doing in the life of Wild Bill; then as now, Hollywood realism didn’t mean adherence to the facts. (Oddly enough, when Josephine Earp wrote to Hart after seeing Wild Bill Hickok, she congratulated Hart on his performance, but never thought to comment on the film’s portrayal of her husband. Perhaps she did not know; perhaps Earp never told her.)

Hart’s reign at the top of the movie cowboy chain was short lived. By the mid-1920s, fans wanted flashier stories and gaudier productions. Thomas Hezekiah Mix from Mix Run, Pennsylvania, had been a Western star before the movies, having toured with the Miller Bros. 101 Ranch Wild West Show and ridden with former Deadwood lawman Seth Bullock in Teddy Roosevelt’s inaugural parade in 1905. On the big screen, Mix was dynamic, the Douglas Fairbanks of the saddle. “His presence,” wrote Richard Schickel in his 1962 book, The Stars, “was enough to make the disciple of pure Western form shudder.”

His first features were for Selig Polyscope, the first permanent movie company in the Edendale district; Mix worked with Selig for seven years, from 1910-1917, then moved to Fox, where he was known for his own signature brand of flamboyant costumes replete with enormous wide-brimmed cowboy hats. “It was not until Hart fell out of step with his time,” wrote Schickel, “that Tom Mix became the ranking screen cowboy.”

Mix’s version of the West was much more romanticized than Hart’s. Realism bored him, and the idea of being anything as subtle as a good bad man was quite beyond him. The West was, for him, merely an abstraction—a convenient, stylized backdrop against which to act out his simple dramas of heroism.

The contrast between Hart and Mix was evident not just in their films, but also in their choice of homes. Hart’s simple, stately Spanish Colonial home in Santa Clarita, about an hour’s drive from Los Angeles, would become the William S. Hart Ranch and Museum. Mix’s palatial, Moorish-style mansion at 1010 Summit Drive in Beverly Hills was practically a museum with ornate woodwork, high ceilings and rooms that were, like Charles Foster Kane’s fictitious Xanadu, filled with Venetian furniture and other lavish trappings. Fountains sprayed streams of blue-, pink- and red-colored water; at night his TM brand lit up in neon from the roof of his mansion.

No one knows how Mix and Earp met, but one newspaper spotted them together at Mix’s favorite restaurant, Musso & Franks Grill, on Hollywood Boulevard, possibly enjoying the signature steaks and the “real gimlet,” of which writer Raymond Chandler was so fond. Opened in 1919, it was, or so its owners billed it, the “oldest eatery in Hollywood,” and it still thrives today.

The sun would set on Mix’s style of Westerns as surely as it had on Hart’s. The early seeds for the new Western were planted by John Ford, who, using Harry Carey, a star who proved more durable than Hart or Mix, added new gravitas to the Western with Ford’s first feature film, 1916’s Straight Shooting. (His popular Carey pictures paved the way for his first epic production, 1924’s The Iron Horse.)

Earp was a frequent visitor to the Carey/Ford sets. Many years later, Ford’s son Patrick recalled, “My dad was real friendly with Wyatt Earp, and as a little boy I remember him…. But I was too young to grasp what Wyatt Earp was saying. I only remember him saying one thing: ‘The only way to be a successful marshal in those days was to carry a double-barrel, 12-gauge [shotgun] and don’t shoot until you know you can’t miss.’”

It’s a wonder that line never made it into a Wyatt Earp movie.

Earp and Josephine lived in genteel poverty in rented homes and apartments around Los Angeles. Sometime in the mid-1920s, when the Earps were living in a shack in Vidal, California, near the Arizona border, a friend Earp had known in Alaska, Charles Welsh, invited them to live in his top floor apartment in LA. This may have been where most of the work was done on Wyatt’s “autobiography” by a family friend and former mining engineer, John Flood.

The mysteries surrounding the various versions of the so-called “Flood manuscript” would fill a book. The biggest mystery of all is perhaps why Earp didn’t seek help from writers he knew who might have been able to tell his story with a great deal more skill than Flood, such as Jack London or the playwright, scriptwriter and all-around raconteur Wilson Mizner. Earp got to know Mizner in Alaska, and he renewed their friendship in 1926 when Mizner moved from New York to LA to manage the first Brown Derby restaurant on Wilshire Boulevard.

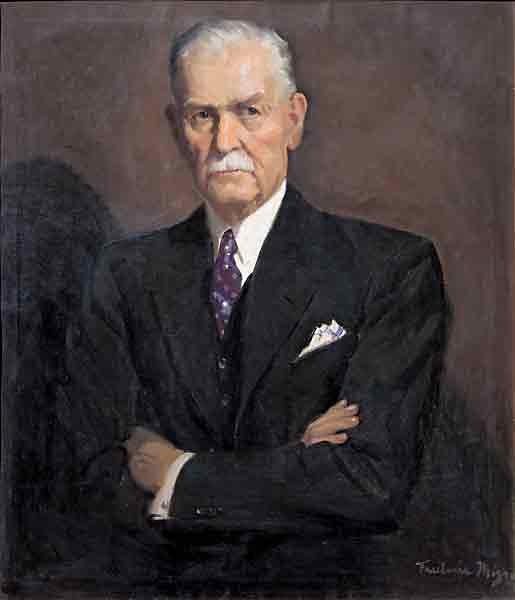

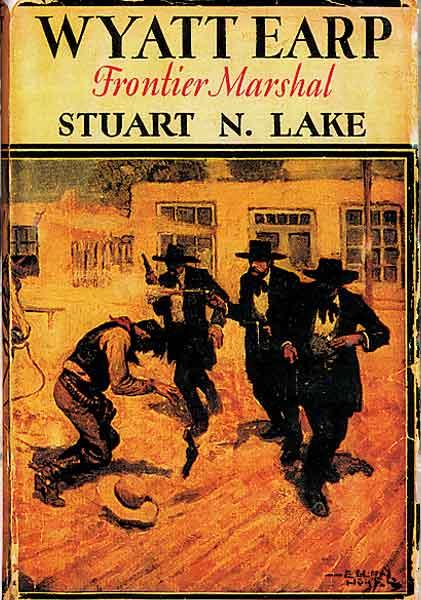

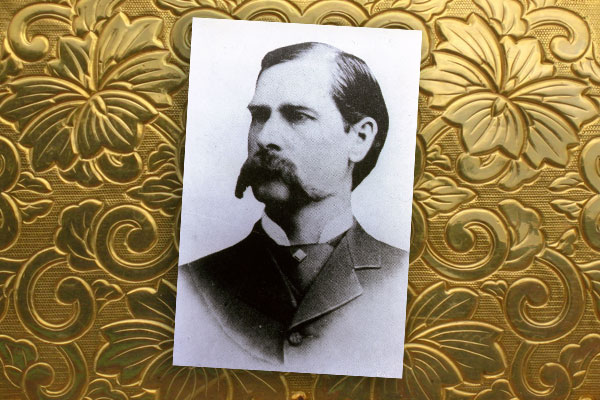

The main reason Flood’s manuscript wasn’t bought by a publisher or a Hollywood studio, despite the determined support of William S. Hart, was that it was simply awful—stilted, corny and one-dimensional. Not until 1931—two years after Earp’s death and 50 years after the street fight in Tombstone in back of the O.K. Corral-—did Stuart Lake, former press secretary for Teddy Roosevelt, win the Earp movie sweepstakes with Frontier Marshal, the book that helped make Earp more famous than any of the Western actors he palled around with in Hollywood.

Lake’s book came along at precisely the right time. American cities were reeling from gun battles between bootlegging gangsters, and the country had gone just far enough beyond the passing of the frontier to feel nostalgic for its heroes.

Now everyone knew about one of those heroes, Wyatt Earp, who had died on January 13, 1929. The pallbearers included his frontier friends from Arizona and Alaska, George Parsons and John Clum, as well as his cowboy movie pards, William S. Hart and Tom Mix.

Shortly after Wyatt’s death, and a year before Lake’s book was published, Raoul Walsh began work on The Big Trail, one of the first widescreen sound Western features. The star of the film was a young football player, John Wayne, who had been recommended to Walsh by Ford.

It was the end of an era and the beginning of a new, more sophisticated one that, combined with the harsh economic realities of the Great Depression, killed off many of the smaller film companies. By 1935 Mix, who had once made the astonishing sum of $17,500 a week, was out of the movie business.

In 1939 John Ford, who had just had a huge success with his archetypal Western, Stagecoach, was visited by a ghost. Mix, age 59, needed a job. A shaken Ford could only reply, “Jesus, Tom, we don’t make pictures like we made with you years ago.”

The next year, Mix was killed in a car accident. If he had lived just six more years, Ford might have been used him in a character role in his sugarcoated bio of Earp, My Darling Clementine. They don’t make pictures like that anymore either.

Allen Barra is the author of Inventing Wyatt Earp, a feature writer for The Wall Street Journal, a sports columnist for TheAtlantic.com, a contributing writer for The Daily Beast and a book critic for American History magazine. His forthcoming book is Mickey and Willie: Mantle and Mays, the Parallel Lives of Baseball’s Golden Age.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Historical & Special Collections, Harvard Law School Library

– Courtesy Brian Lebel’s Old West Auction –

Allie, the wife of Wyatt’s brother Virgil, outlived her husband by 42 years and spent her last years in LA, where she cleaned houses for a living. She cleaned Frank Waters’ house, and he created a manuscript from her experiences, which, as you might imagine, favored Virgil. When Wyatt’s widow, Josie, heard about this, she arrived at the Waters’ home, unannounced, and proceeded to create such a scene that Frank’s mother almost had a heart attack. Needless to say, Frank was not a fan of Wyatt’s wife (and, some say, Wyatt, by extension). His manuscript, which sat dormant for many years, was finally published in 1960 as The Earp Brothers of Tombstone. It is a very negative portrayal of all the Earps. Allie lived long enough—she died in 1945—to see many of the movies about Wyatt Earp; she pronounced them all as “Gingerbread.”

Stuart Lake’s tome about Wyatt Earp (left) came out in 1931 and has been the fodder for numerous movies. This cover is notorious because Doc was left out of it; the cover was later redone to show all four members of the Earp party.

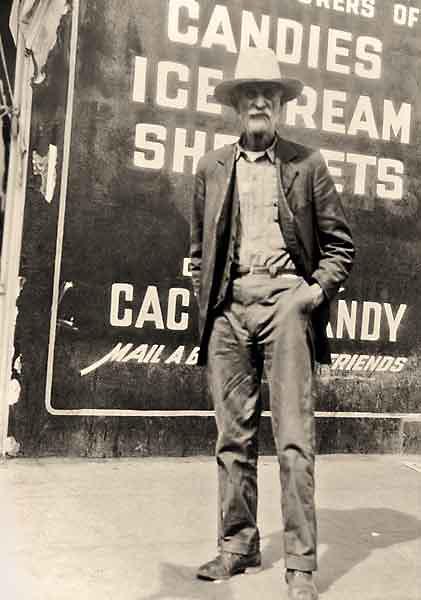

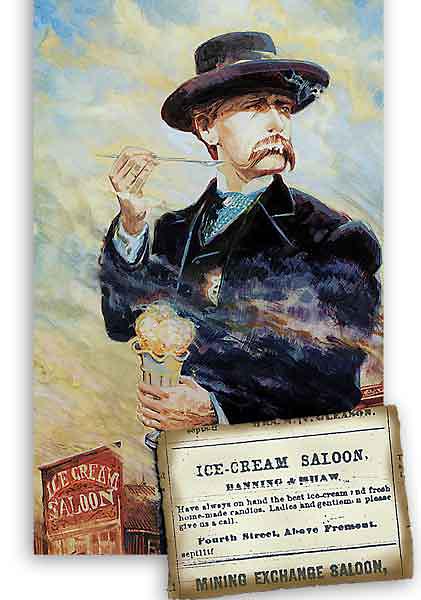

Wyatt Earp enjoyed eating ice cream in Tombstone. In an estate case in 1925, Wyatt testified, “I met her [Jack Crabtree’s wife] at an ice cream parlor…on Fourth Street between Allen and Fremont…I used to go there pretty often. I liked ice cream and I met her over there.” The ice cream parlor Wyatt is referring to appearsin the ad at left which ran in the Tombstone Nugget in 1881. The idea of Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday ordering ice cream in the wildest camp in the west (“I’ll try the Huckleberry!”) is a sight to imagine. Wyatt, his brothers and Doc walked by this very “saloon” on their way to the gunfight.

– Illustration by Bob Boze Bell –

– Courtesy Lee Silva –

– Courtesy Jeff Morey –