Old West novelist and journalist Emerson Hough called the moccasin “one of the most interesting articles of all the Indian gear.”

Old West novelist and journalist Emerson Hough called the moccasin “one of the most interesting articles of all the Indian gear.”

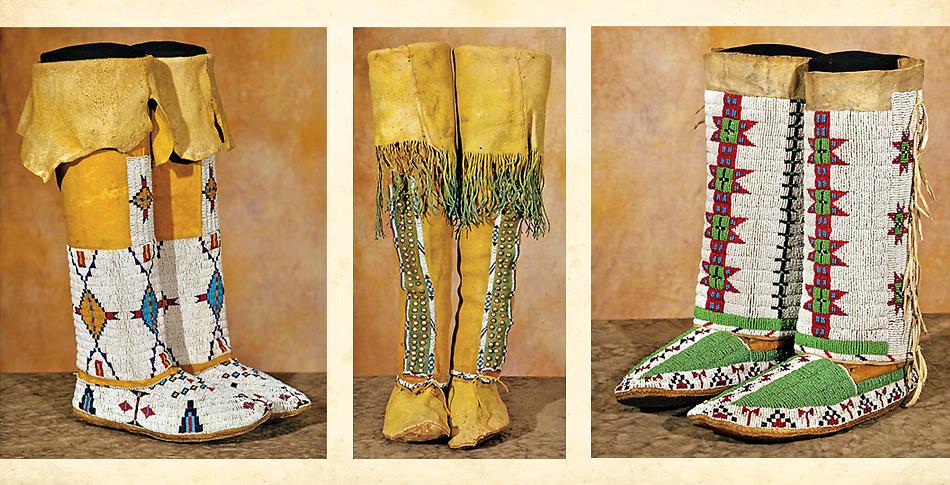

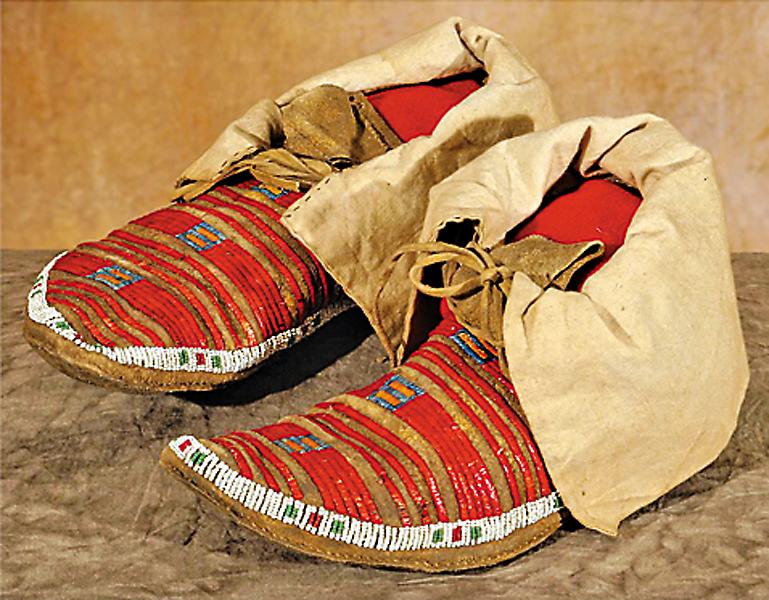

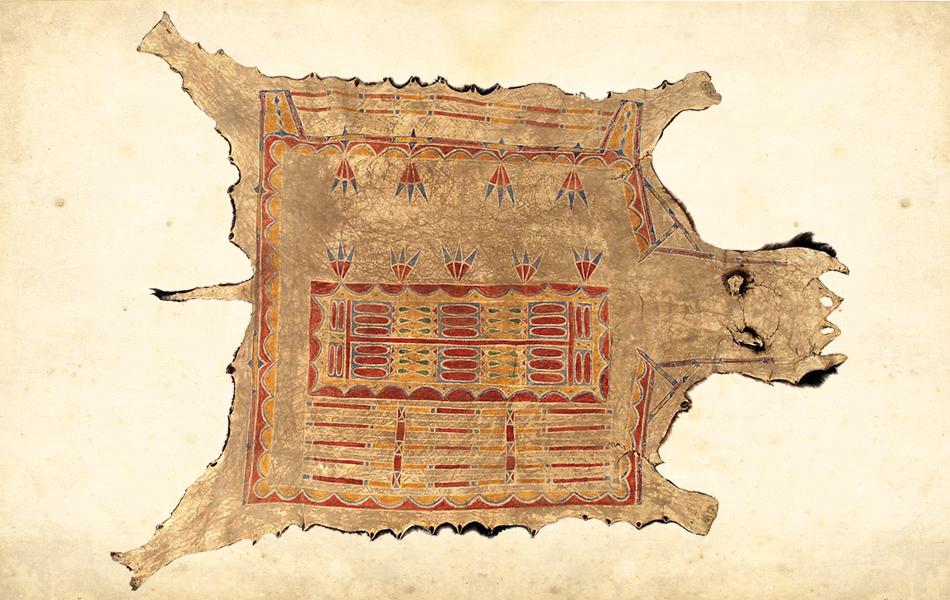

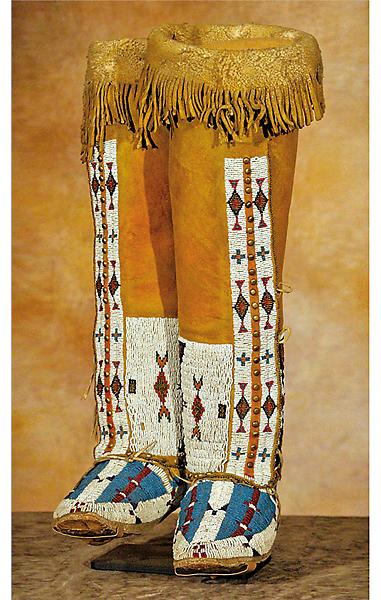

The story told by the moccasin, in its 19th-century form, was expressed by the nearly 40 moccasin collectibles that sold on the auction block at New Mexico’s Auction in Santa Fe on August 11-12.

The symbolic figures crafted on these small canvases reflect the reality that the various tribal Indians were not working with flexible or adaptable materials, and were limited in their designs based on the quills or trade beads that were on hand. Each symbol became a labor-saving device, a shorthand in art. “When we read his moccasin story,” Hough wrote, “we read a shorthand, in which the characters are syncopated pictures.”

The symbols were so unique and individualistic that not only would they differ within tribes, but also within families, so no two Indians would offer the same interpretation for a moccasin presented to them both. Yet since environment so often determined the type of moccasin worn by a tribe, every member could identify what tribe had made the moccasin (or which tribe has left its mark in the ground or snow). This was true, to a point. For example, 19th-century Blackfeet, Cheyenne and other Plains Indian tribes who lived up north in colder environments wore soft soles, so the track would have to indicate some other distinguishing feature, such as toe forms or heel fringes, to determine which tribe had left the mark. In at least enough cases, the trick did work. Frontiersman Kit Carson told his biographer De Witt Clinton Peters, “The shape of the sole of the moccasin…and many other like things, are sure signs in guiding the experienced trailer to the particular party he is seeking.”

In 1878, an officer reported seeing some Cheyennes. Troops from Montana’s Fort Keogh went out on the trail to intercept them. Their Cheyenne scout “Poor Elk” located some bits of moccasins and noted how they “were sewed with thread instead of sinew, and were made as the Sioux made theirs.” W.P. Clark, who reported this account in 1885, pointed out how the “record left by these Indians was as complete as though it had been carefully written out.” The Sioux had been traveling through that country, not the Cheyennes.

Since many of us no longer require an education in moccasins to aid us in tracking a particular tribe, we can enjoy these collectibles for their decorative qualities, keeping in mind that the symbols expressed on these moccasins cannot be read, only interpreted. As Hough wrote, the mystery is worth savoring, “…if through it we can hear again the whisper in the untrodden verdure of the Plains, and note the message of the sky, and see the sunrise on the peaks, and witness the wild peopling of an unravaged land; and so catch again the wild, crude flavor of the wilderness and a day gone by.”

Collectors earned more than $1 million on the sale of their Indian collectibles.

Photo Gallery

– All images courtesy Auction in Santa Fe –