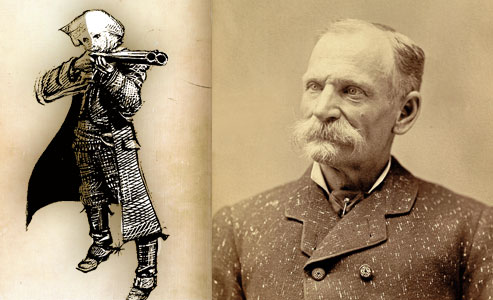

Acquaintances knew the gentleman as Charles Bolton, a 50ish, affable owner of a mine outside San Francisco, California. He sported a cane, derby hat, diamond pin, diamond ring and a gold watch and chain.

Acquaintances knew the gentleman as Charles Bolton, a 50ish, affable owner of a mine outside San Francisco, California. He sported a cane, derby hat, diamond pin, diamond ring and a gold watch and chain.

He was relatively well educated, a patron of theatres and music halls, and ate at the best restaurants in town. Polite to a fault, especially to ladies, he hobnobbed with the San Francisco elite. On occasion, he disappeared for days or weeks at a time, ostensibly to oversee his mining interests.

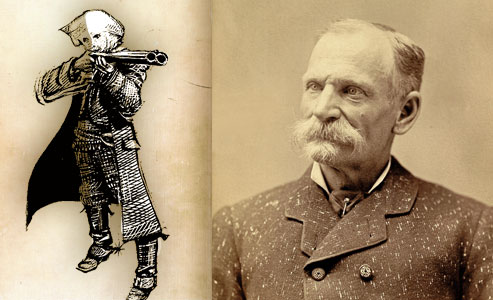

Unbeknownst to his San Francisco acquaintances, Bolton supported himself by robbing stagecoaches in California’s gold country. Calling himself Black Bart, he logged some 29 holdups between 1875 and 1883. The exact number is in question, since his covered face hid his true identity and he was only prosecuted for his final attempt.

His unsavory means of support notwithstanding, Bolton considered himself a San Francisco gentleman and tried to look and act the part. However an examination of his life raises some serious questions about his character. Indeed, his pretensions did not always translate into gentlemanly behavior.

Black Bart had several aliases. Born Charles Bowles (sometimes spelled Bolles or Boles), he used Charles Bolton during his years in San Francisco—and during his prison sentence at San Quentin. Upon his arrest, he gave his name as T.Z. Spaulding. The moniker “Black Bart,” with which he signed poems left at the sites of two of his holdups, was obtained from the villain in William H. Rhodes’s The Case of Summerfield, a novel first serialized in the Sacramento Daily Union in May and June of 1871.

Even as a bandit, he played the gentleman role to a fault. Although he held up stages at gunpoint, he scrupulously avoided bloodshed and acted courteously to the terrified passengers, refusing their money and valuables. His interest rested exclusively with the Wells Fargo express box and the U.S. mail. During his first robbery, on July 26, 1875, near the top of Funk Hill at the head of Yaqui Gulch, he politely requested the Wells Fargo box. When a thoroughly frightened woman passenger threw her purse out of the window, he gallantly returned it with the words, “I don’t want your money—only the express box and mail.”

Courage was not always his strong suit. On November 20, 1880, he attempted to hold up a stagecoach near the Oregon border. Although he was holding a rifle, he fled when feisty driver Joe Mason threatened him with a hatchet. On July 13, 1882, in an attempt to rob the LaPorte to Oroville stage, Black Bart was shot at by veteran Wells Fargo messenger George Hackett and slightly wounded in the head, causing him to lose his hat. Again, he made the choice of flight rather than fight. His avoidance of bloodshed seemed to apply as much to himself as to his victims.

His behavior was curious given that Bolton had served heroically during the Civil War. In 1862, he enlisted as a Union private in Company B of the 116th Illinois Volunteer Infantry. He participated in 17 battles, including the one at Vicksburg, and sustained three wounds. Rewarded for his service by promotion to sergeant, he was also offered a battlefield commission as first lieutenant. Perhaps his advancing age had deprived him of his youthful courage, or perhaps his behavior could be attributed to mature reflections on the horrors of the Civil War.

For the robberies he carried out after the Civil War, he worked alone and on foot. His preferred mode of operation was to ambush a stagecoach on an upward incline, or in a place where it was forced to move slowly. His head covered with a flour sack cut with eye holes, he would stand in front of the lead horse, point a shotgun at the driver and demand the express box and U.S. mail pouches. He never shot at anybody and later claimed that his shotgun was never loaded. Though far from young, he seemed well adapted to efficiently hiking long distances in regions where roads were sparse or nonexistent. Without accomplices or horses, he was able to evade the law for over eight years.

Fancying himself a poet, Black Bart authored two short poems, with a total of 12 lines. After his fourth and fifth stagecoach robberies, he left behind a poem signed “Black Bart, the P o 8.” In both, we can find further clues to his character. His first poem is likely directed at Wells Fargo:

I’ve labored long and hard for bread

For honor and for riches,

But on my corns too long you’ve tred

You fine-haired sons of bitches.

–Black Bart, the P o 8.

Given his target of Wells Fargo boxes at holdups, he must have had a grievance against the express company. The rebel attitude of others who had fought in the Civil War was more common on the Confederate side, as in the case of Jesse James, who raged against companies that dominated the economic landscape, like Wells Fargo with its near monopoly of business in the West. But the reason for Black Bart’s angst is unclear. “But on my corns too long you’ve tred” implies he may have had a personal reason for his grievance.

His Civil War service makes it unlikely that he had a serious grudge against the U.S. Government. His lifting of mail bags looked like a profitable convenience. After all, they pretty much came with the Wells Fargo box. His second poem, left at the site of his fifth robbery, clarifies he was no Robin Hood and stole simply for profit:

Here I lay me down to sleep

To wait the coming morrow.

Perhaps success, perhaps defeat,

And everlasting sorrow.

Let come what will, I’ll try it on,

My condition can’t be worse;

And if there’s money in that box

Tis munny in my purse.

–Black Bart, the P o 8.

His claims to gentleman status are further eroded when we consider his caddish treatment of his wife and family. In 1854, he married Mary Elizabeth Johnson in Jefferson County, New York, after a failed attempt to strike it rich during the California gold rush. They moved to Illinois and later Iowa, and raised three daughters. After the Civil War, Bolton rejoined his family in Iowa, had a fourth child, a son, and then left in 1867 to mine for gold in Montana Territory. Eight years later, he showed up in California gold country once again, this time as a gentleman bandit. His family never saw him again.

Mary moved to Hannibal, Missouri (Mark Twain’s hometown), and made ends meet by sewing. She and Charles renewed their relationship through correspondence during his tenure in San Quentin. His surviving letters offer professions of undying love for his family, profuse confessions of remorse and gratitude for her forgiveness. They are, frankly, nauseating by modern standards, though consistent with the conventions of the day. Mary, for her part, seemed genuinely willing to take him back upon his release. In any event, she was disappointed, as he never returned to her, his sentimental Victorian prose notwithstanding.

His 29th holdup, on November 3, 1883, proved Black Bart’s undoing. Interestingly, it occurred at the site of his first robbery. Black Bart, who had only a few run-ins with armed messengers, was ill prepared for his chance encounter with a hunter, 19-year-old Jimmy Rolleri. Armed with a Henry rifle for his deer hunt, Rolleri had been dropped off on the way up Funk Hill by Sonora-Milton stage driver Reason McConnell, who continued up the incline. Near the top, Black Bart, lying in wait, made his move. At gunpoint, he ordered McConnell to unhitch the horses and continue up the hill while Black Bart went to work on the Wells Fargo box bolted to the floor. While proceeding with the horses, McConnell spotted Rolleri and signaled to him. Once McConnell informed Rolleri of the situation, the hunter handed over his rifle. McConnell fired twice at Black Bart, missing him both times. Rolleri took the rifle and fired, winging Black Bart in the hand. The gentleman bandit fled.

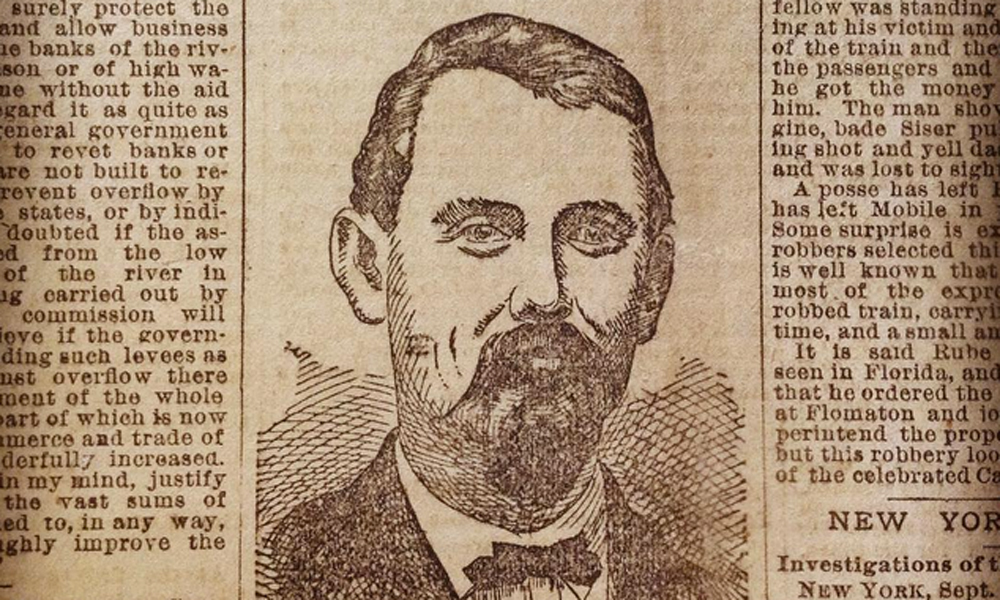

In his haste to put distance between him and the hunter, Black Bart left behind several possessions. In particular, a handkerchief with a laundry mark led to a search of San Francisco laundries that made it possible for Wells Fargo Chief Detective James Hume and his associates to identify Black Bart as Charles Bolton, a San Francisco mine owner.

Subjected to a grilling by Hume and Detective Harry Morse, Bolton, true to form, repeatedly protested that such treatment was inappropriate for a gentleman. Yet he ultimately confessed and led the lawmen to the hollow log where he had stashed the stolen gold. Brought before the Calaveras County Superior Court, he pleaded guilty to a single robbery charge and was sentenced to six years in San Quentin. A model prisoner, he was set free after four years and two months.

After his release, Black Bart briefly rented a room in the Nevada House hotel in San Francisco. He then apparently traveled down the San Joaquin Valley, visiting Modesto, Merced and Madera, and checked into a hotel under yet another alias—this time Mr. M. Moore—in Visalia. Then he disappeared. He was, perhaps inevitably, suspected of a few subsequent stage robberies, but the evidence was, at best, flimsy. For all intents and purposes, Black Bart vanished from the face of the earth.

The late 19th-century American West had its share of contradictions. Elaborate and sentimental Victorian mores conflicted with a climate where violence was all but routine, and law and order was often tenuous. Black Bart’s character and behavior seem to have embodied these incongruities. His gentlemanly lifestyle, nonviolent attitude and respectful treatment of passengers can all be seen as a triumph of one set of values over another. One might even detect a hint of revulsion at the unprecedented carnage of the Civil War, which he had experienced firsthand. But, in the end, he was a classic bad guy, a masked man who had stolen money at gunpoint for his own profit.

Black Bart’s California Stage Robberies

2. Dec. 28, 1875, Yuba County: North San Juan to Marysville stage. Taken: Unknown.

3. June 2, 1876, Siskiyou County: Nighttime robbery on the Roseburg, Oregon, to Yreka, California, route. Taken: $80 plus mail sack contents.

4. Aug. 3, 1877, Sonoma County: Between Fort Ross and Duncan Mills, on Russian River. Taken: $300 in gold coins and a $305 check. Poem: First poem.

5. July 25, 1878, Butte County: Quincy to Oroville stage. Taken: $379 in coins, $200 diamond ring, $25 watch and mail sack cash. Poem: Second poem.

6. July 30, 1878, Plumas County: LaPorte to Oroville stage. Taken: $50 in gold, a silver watch and mail sack cash.

7. Oct. 2, 1878, Mendocino County: Cahto to Ukiah stage. Taken: $40, a watch and money from mail sacks.

8. Oct. 3, 1878, Mendocino County: Covelo to Ukiah stage. Taken: Unknown.

9. June 21, 1879, Butte County: Stage from Forbestown to Oroville. Taken: Unknown.

10. Oct. 25, 1879, Shasta County: Nighttime robbery on the Roseburg, Oregon, to Yreka-Redding, California, stage. Taken: Undisclosed sum from Wells Fargo and $1,400 from mail pouches.

11. Oct. 27, 1879, Shasta County: Alturas to Redding stage. Taken: Unknown.

12. July 22, 1880, Sonoma County: Point Arena to Duncan Mills stage. Taken: Undisclosed sum. Whether robber was Black Bart remains a point of contention.

13. Sept. 1, 1880, Shasta County: Weaverville to Redding stage. Taken: A little more than $100.

14. Sept. 16, 1880, Jackson Cty. OR: Second nighttime robbery of Roseburg, Oregon, to Yreka, California, stage, occurring one mile north of state line. Taken: Approximately $1,000.

15. Sept. 23, 1880, Jackson Cty. OR: Roseburg, Oregon, to Yreka, California, stage, robbed three miles north of border. Taken: Nearly $1,000 and mail sack.

16. Nov. 20, 1880, Siskiyou County: Roseburg, Oregon, to Redding, California, stage, south of state line. Taken: Unknown.

17. Aug. 31, 1881, Siskiyou County: Final robbery of Roseburg, Oregon, to Yreka, California, stage. Taken: Unknown.

18. Oct. 8, 1881, Shasta County: Midnight robbery of Yreka to Redding stage, near Bass Hill. Taken: $60.

19. Oct. 11, 1881, Shasta County: Alturas to Redding stage stops at Montgomery Creek for harness repair and is robbed again. Taken: Unknown.

20. Dec. 15, 1881, Yuba Count: Downieville to Marysville stage. Taken: Wells Fargo reports “small loss.”

21. Dec. 27, 1881, Nevada County: North San Juan to Smartsville stage. Taken: Wells Fargo reports “small loss.”

22. Jan. 26, 1882, Mendocino Cty.: Ukiah to Cloverdale stage. Taken: Unknown.

23. June 14, 1882, Mendocino Cty: Willits to Ukiah stage. Taken: Estimated $300 and mail sack contents.

24. July 13, 1882, Plumas County: Shotgun blasts foil Black Bart at LaPorte to Oroville stage. (A buckshot pellet creases the robber’s forehead, leaving a deep scar.)

25. Sept. 17, 1882, Shasta County: Second robbery of Yreka to Redding stage at Bass Hill. Taken: Thirty-five cents.

26. Nov. 23, 1882, Sonoma County: Lakeport to Cloverdale stage. Taken: $475 and several mail sacks.

27. April 12, 1883, Sonoma County: Lakeport to Cloverdale stage robbed again. Taken: $32.50 and mail sack contents.

28. June 23, 1883, Amador County: Stage from Jackson to Ione. Taken: $750 and mail sack contents.

29. Nov. 3, 1883, Calaveras County: Sonora to Milton stage is stopped at site of first Black Bart holdup in 1875. Taken: Possibly $4,764.

Daniel R. Seligman is a retired engineer who lives in Needham, Massachusetts. For those who would like to read up more on Black Bart, he recommends: “The Case of Summerfield” by William Henry Rhodes, Black Bart: Boulevardier Bandit by George Hoeper and Black Bart: The Poet Bandit by Gail L. Jenner and Lou Legerton.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Brian Lebel’s Old West Auction –

– Courtesy Richard Rolleri –

– True West Archives –