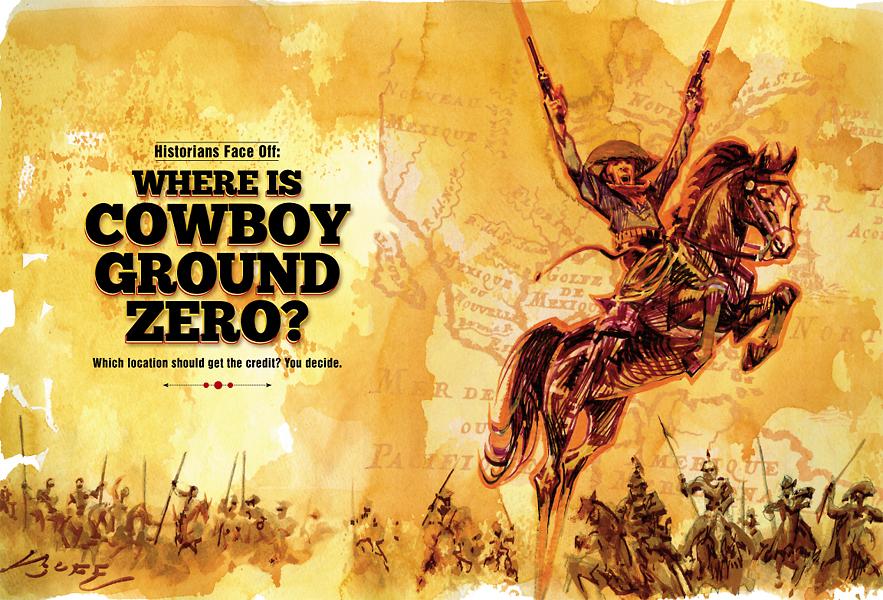

Most of us agree the American Cowboy was born somewhere in Texas but metaphorically speaking, where were his parents from? If we ride the backtrail in search of the origins of that legendary breed of horsemen where would that trail lead us? Three passionate historians, Lee Anderson, Alan Huffines and Stuart Rosebrook make their case for the true location of Cowboy Ground Zero.

Most of us agree the American Cowboy was born somewhere in Texas but metaphorically speaking, where were his parents from? If we ride the backtrail in search of the origins of that legendary breed of horsemen where would that trail lead us? Three passionate historians, Lee Anderson, Alan Huffines and Stuart Rosebrook make their case for the true location of Cowboy Ground Zero.

The Case For North Africa: By Stuart Rosebrook

When I was ten years old, growing up in North Hollywood, California, I’d probably tell you that “Cowboy Ground Zero” was in the San Fernando Valley, home of Republic Pictures and Warner Brothers Studio.

Hollywood aside, history will tell us that from the Scottish Highlands to Mexico City, Mexico, from tropical, sub-Saharan West Africa to the Celtic lowlands of Ireland, the cowboy of the Americas can claim parentage from many kingdoms. Scholars also argue that the birthplace of the cowboy may actually be in Andalucía, Spain, at a mythic crossroads on the arid plains of southwestern Spain where Moorish cavalry met Castilian knights in battle over the fertile Iberian peninsula for the greater glory of God and gold. In fact, I’d argue that the birthplace of the cowboy is in the Atlas Mountains of Algeria.

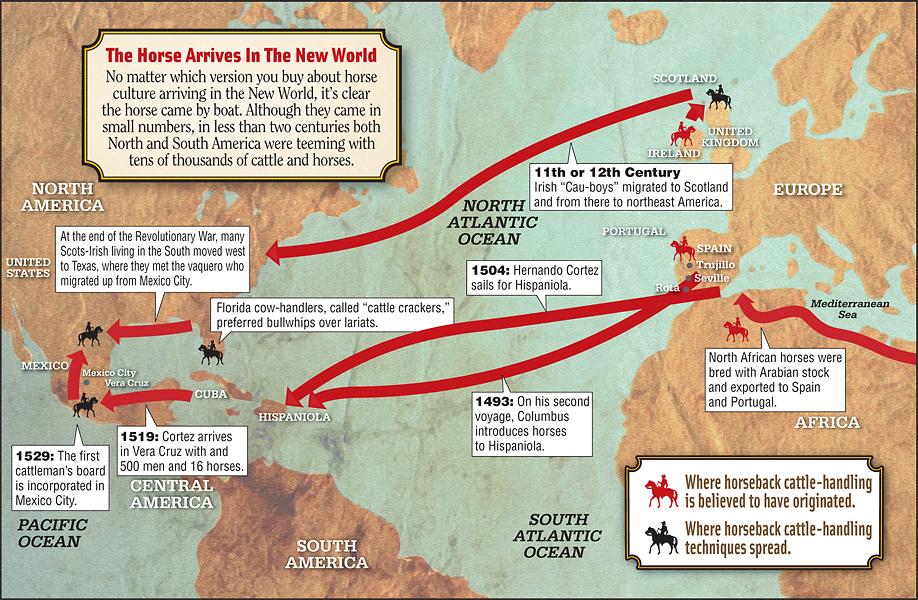

In the sixth and seventh centuries, Arabian armies had conquered and converted the Berber tribes of North Africa. One of the tribes, the Zeneta Berber, astride their Arab Barb’s in light saddles with short stirrups, armed with light swords and pikes, were legendary for their swift and deadly cavalry. In 711 A.D., former Berber Zeneta slave, Tariq ibn Ziyad, led

7,000 Moors ashore at Gibraltar, all riding Zeneta style, where they met in battle Spanish knights, riding la brida, the style of riding with long stirrups and armor of medieval Europe. For the next eight centuries, the Moors dominated much of the Iberian Peninsula, especially the great cattle ranching regions of Extremadura and Andalucía, bringing their knowledge and science of horse and cattle breeding, including breeds from North Africa, into Spain. The Zeneta style of riding was soon known throughout Spain as la jineta.

Slowly, over nearly 800 years, la jineta became the preferred style of equestrianism for the Spanish cavalry. The Spaniards also developed a new horse to defeat the Moors, the Spanish Barb, bred from the Arab Barb and larger Spanish war horses. On January 1, 1492, When King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella accepted the surrender of the Moors in Granada, Andalucía, Spain, the Spanish la jineta style cavalry mounted on their Spanish Barbs were regarded the best in the world.

Following the Reconquista in 1492, the Spanish were the most powerful Roman Catholic kingdom in Europe. Despite the Iberian victory, the Islamic Ottoman Empire still controlled much of North Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean, blocking most of the spice and silk trade routes to India. Ferdinand and Isabella, eager to compete with the Portuguese, who had trade routes going East around the Cape of Good Hope, hired Italian navigator Christopher Columbus to sail West in search of a shorter route to the treasures of the East Indies. In 1493, on his second journey, Columbus brought the first Spanish horses and cattle, with their Arab bloodlines, to the New World. Twenty-five years later, Conquistador Hernán Cortés conquered Mexico with his cavalry riding Spanish Barbs la jineta style against the horseless Aztecs. Over the next few decades, according to historian Kathleen Mullen Sands in Charreria Mexicana, a new style of American equestrianism began to develop, called la bastarda, which lengthened the stirrups and adapted the saddle for ranching and herding in the rough and varied terrain of New Spain, but it was the Berber la jineta and the Arab Barb which led to Spain’s emergence as the greatest horseman in the world when the cataclysmic era of exploration began in 1492.

So, if you ask me, where is Cowboy Ground Zero I’d book passage from Gibraltar to the port of Saidia, Algeria, hire a local guide to lead you into the Atlas mountains of Northwest Algeria, the traditional home of Gibraltar’s namesake, Tariq ibn Ziyad, and you just might meet the descendants of the mounted Moorish warriors of North Africa still riding la jineta on their fleet-footed Arab Barb’s, herding ancient bloodlines of Algerian cattle.

Stuart Rosebrook, senior editor at True West, has trailed many miles on horseback through central Arizona, but would love to ride in the Atlas Mountains of Algeria in search of cowboy ground zero.

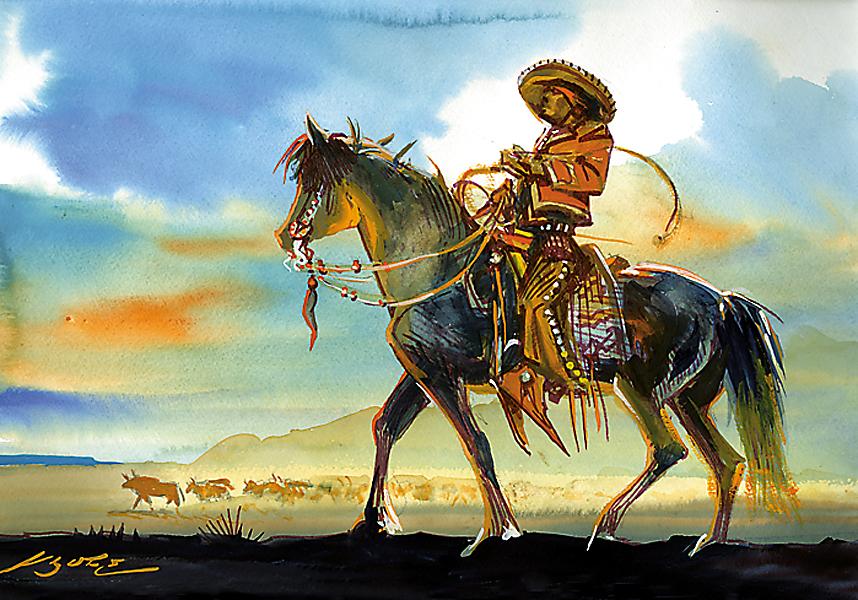

The Case For Mexico: By Lee Anderson

The first foundation stone for cowboy culture was laid on June 16, 1529, in Mexico’s municipality of Mexico City. On that day, the first cattlemen’s board, called Mesta, was incorporated. Among Mesta’s duties was the settlement of disputes over whose cattle and horses were allowed to roam and where. In addition, the Spanish government administrative committee ordered, “Two officers of the Mesta shall reside in the city who shall, twice annually, call together all stockmen who shall make it known whether they have any stray animals in their herds.”

In other words, the law required a spring and a fall roundup.

The Mesta further required each rancher had a unique brand and registered it in a brand book kept in Mexico City. These

rules for the spring and fall roundups became the model

for those conducted by the Americans three centuries later. Nowhere else in the world had such cattlemen’s rules been established, mandated and legally enforced by a country’s governing body.

The branding mandate led to the vaquero developing the art of roping, the most efficient method for capturing, subduing and branding wild cattle in the wide open. Before long, the vaquero realized that once he got one end of his rope around a 900-pound wild cow, he had a problem with the other end, the one he was holding. This led to the development of the saddle horn. Both the art of roping an animal from horseback and the saddle horn as cowboy gear are unique to the vaquero culture, and both were passed on to the American cowboy in the 1800s.

Even though the cattle that were the foundation stock in this hemisphere were imported from Spain, cattle here and cattle there developed differently. While the cattle in Spain were unquestionably mean, they were still a domesticated animal, confined in a fenced area, and the product of selective breeding. When they were turned loose in Mexico City, they became feral and selective breeding was not practiced. When a 900-pound longhorn cow or a 1,200-pound longhorn bull with a mean nature turns feral, you encounter an entirely different set of problems than if the cow or bull was simply mean. The cattle-handling methods utilized in Spain proved to be pretty much useless in New Spain, as Mexico was called.

Most important in this matter were the Spanish laws at the time concerning the importation of horses and cattle. The law forbid anyone, except the politically and socially elite and the military, to ride a horse. A mounted military kept the native population and Spanish colonists under control. After all, horses were the leading edge of military technology. The common people were not allowed to ride horses for the same reason a civilian today can’t own an Abrams tank. By the early 1500s, when Mexico was being colonized, the Spanish military was known the world over for producing some of the finest horsemen on earth, not the finest cattle handlers.

The peons, mostly natives converted to Christianity and called neophytes, were tasked with looking after Mexico City’s wild cattle. Since they were not permitted to use horses, they had to watch over the cattle on foot. Cattle were an extremely important economic engine in Mexico, raised not for beef, but for hides and tallow. Leather was the plastic of that time and candles, being the primary source of artificial light, produced a demand for tallow.

In this unfenced land, the cattle herds became huge, numbering in the thousands. They also became so wild and dangerous, and they ranged over so much area, that looking after them on foot became impossible. The economic value of cattle dictated that a solution had to be found. Ranchers and mission padres petitioned the government to allow them to teach a few of the more trusted neophytes to ride horses in order to perform their job.

At this point, the military became a key feature. The politically or socially elite were not about to stoop to teaching lowly peons to ride a horse. No, the job of teaching them fell to the military, and because it did, I believe cowboy ground zero is somewhere in the Mexico City vicinity. The military taught these peons only the ability to handle and ride horses, not how to look after huge herds of mean feral cattle. They were soldiers and horsemen; they knew nothing about handling cattle. No, the now-mounted peons had to figure out how to cope with these beasts on their own because nowhere on earth had anyone ever dealt with the unique problems the peons ran into with these cattle and the harsh environment in which they lived.

Military horsemanship did serve these cattlemen well. The challenges of fighting on a battlefield and handling cattle shared similarities. For instance, a rider who had both hands full of reins could not handle a weapon to fight his enemies, just like he could not throw a rope on cows to keep them in control. He never knew where he might find his enemies or his cattle. He didn’t know if they would run or stand and fight. One also sometimes encountered both in uncontrollable weather and terrain. Once a couple of centuries passed, these mounted peons perfected and polished their cattle-handling skills.

The Spanish cattle industry eventually migrated both north and south. In the south, these cattle handlers were called gauchos. In the north, they became vaqueros. The vaqueros exposed the Americans to the art of working with wild, mean cattle.

Therefore, I firmly believe “Cowboy Ground Zero” is in the vicinity of Mexico City and harkens back to the early 1500s. Not only are the wild and mean Longhorn cattle unique to this hemisphere, so are methods such as roping and equipment such as the saddle horn that the

vaqueros were forced to develop for handling the herds. The art of roping

and the saddle horn proved so practical and efficient that American cowboys adopted them, as did several other cattle ranching cultures, most notably those in Hawaii and Australia. The rope (la riata, lariat, lasso), and the skills developed for its use truly set the real cowboys apart from the rest of the world’s mounted herdsmen.

A retired aerospace engineer living in Glendale, Arizona, Lee Anderson has spent more than 60 years studying the Spanish Colonial vaqueros of 1750-1800, the Mexican cowboys of 1850-1900 and the American cowboys of 1880-1920. He is the author of Developing the Art of Equine Communication.

The Case For Ireland: By Alan C. Huffines

In the 11th or 12th centuries AD, the English word “cau-boy” came into being in Ireland. Your first honest-to-goodness cowboys were pale-skinned ginger Hibernians riding around on Celtic saddles and probably pushing the cattle with prods, whether these cowboys were mounted or afoot. Yep, that’s correct—Viking raids, Beowulf and a chieftain named Arthur riding around Britain tried to unify tribes all took place during the time this word appeared.

Back then, “boy” didn’t mean young man, but rather a servant or an employee. The “cau” meant someone who worked with cows. Other popular terms included “cow herd” or “cow herder,” as in shepherd or sheepherder. Before any Arabic and Latin crossed over into vaquero, cowboy was in use. The streets of Cordoba in southern Spain may have been paved and filled with street lamps, but northern Europeans were the ones who herded cows.

Cowboying as a living migrated to Scotland, where all things Gaelic apparently ended up eventually. By the early 17th century, the word had started to mean a “dishonest tradesman.” The Scots and their English lords preferred the term “drover” to make the business sound better. But the job had evolved to stealing or monitoring theft. If you were not a victim of cattle rustling, you probably paid some drovers to protect your herd. This wasn’t in the hired hand sense, but more in the mafia protection insurance. Rob Roy, both the novel and the movie, gives us the best view of Highland cowboys at work.

During the American Revolution, cowboys was a term used almost entirely to describe certain groups of militarized Tories. James DeLancey’s Loyalist Brigade, known to the Americans as DeLancey’s cowboys, were part of the Troop of Light Horse called the Westchester Chasseurs. The New York Gazette, a Tory rag, reported on these cowboys in its October 16, 1777, paper, “…last Sunday Colonel James Delancy with sixty of his Westchester Light Horse went from Kingsbridge to the White Plains where they took from the rebels and took…near 100 head of fat cattle and 300 fat sheep and hogs.”

The ferocity of fighting cowboys is well illustrated in an account left by Samuel Wire’s widow: “…[Private Samuel Wire, Stanton’s Troop, 2d Light Dragoons]…was on a Scout, hunting Cowboys, in company with about twenty five men; he left his company to visit a peach orchard, and near the orchards he discovered a hut. He went up to the hut alone, when a person dressed in a fine green short jacket, trimmed with gold lace, presented himself at the door of the hut and snapped his gun at my husband which missed fire[d]. My husband immediately presented his gun and shot the cowboy through the heart. My husband immediately went around the hut and found another man, which was brother to the one he had just killed, jumping out of the window; He loaded again and shot him through the shoulder, while he was fleeing, and brought him to the ground, and took him prisoner. This man was carried to headquarters, and recovered of his wound. The party which went out in company with my husband stripped the man naked of his clothing, which was very rich, consisting of silver buckles, fine cloths, a gold watch, a valuable gun, and ornaments; all of which were given by the commanding officer to my husband, and were brought home by him. For his service, he told me he was offered a commission from the General, at headquarters, which he declined on account of his age.”

After the Americans won their independence from Britain in 1776, the great migration west began in earnest. In America’s South, this meant primarily Scots-Irish families, many of whom had been cowboys during the war; those who weren’t were able to take up stock farming (not ranching yet) with the amount of cattle and horses available. Though cattle were often tended by men afoot, this practice became impractical with the large amount of feral Longhorns and Shorthorns available in Texas. The mean disposition of these cattle required management from above on a swift platform; the numbers present also meant that more stock could be managed from horseback than foot. Throughout their history, the Scots-Irish had been governed by men who rode horses, who looked down upon them. To be wealthy and powerful, a man needed to be horseback.

Pork is still a popular meat among Mexicans because of the insult eating it has meant to the Islamic conquest of Spain. For the northern European colonists in America, the cow provided everything from food to glue to hinges to work wear. The Scots-Irish colonists in Texas began to eat cattle, and America’s Civil War brought soldiers home

with a taste for beef over pork. Confederates during the war often mentioned getting pork as a ration and how much more they enjoyed it over the usual beef ration. The war and unimaginable quantities of free cattle would increase the popularity of beef.

Cowboy culture as it exists today is both northern and southern European, and it was merged in the great Southwest of the United States of America.

Alan C. Huffines has his BA and MA in history. He is an eighth-generation Texan, board member of the Texas Forts Trail, a retired U.S. Army colonel and gunsel novelist. He makes his home with his wife Caroline and their four children in Buffalo Gap, Texas. Visit AlanCHuffines.com for more information on the author.

So, Who Is Right And What Have We Learned?

As is often the case when you start unravelling something you find it’s connected to everything else in the world. All three arguments (four if you count BBB’s theory, p. 11) have strong and convincing points. Even Stuart’s casual reference to Hollywood possibly being Cowboy Ground Zero has merit. It was mighty convenient the American film industry grew up in the cowboy’s back yard and the subsequent countless portrayals of the horseback hero have exposed an international audience to the daring feats of the now mythic American Cowboy. To borrow a phrase from our friend Paul Andrew Hutton: the American Cowboy keeps riding across the dreamscape of the world’s imagination, forever riding, forever free.

Photo Gallery

– True West Archives –

– All illustrations by Bob Boze Bell unless otherwise noted. –

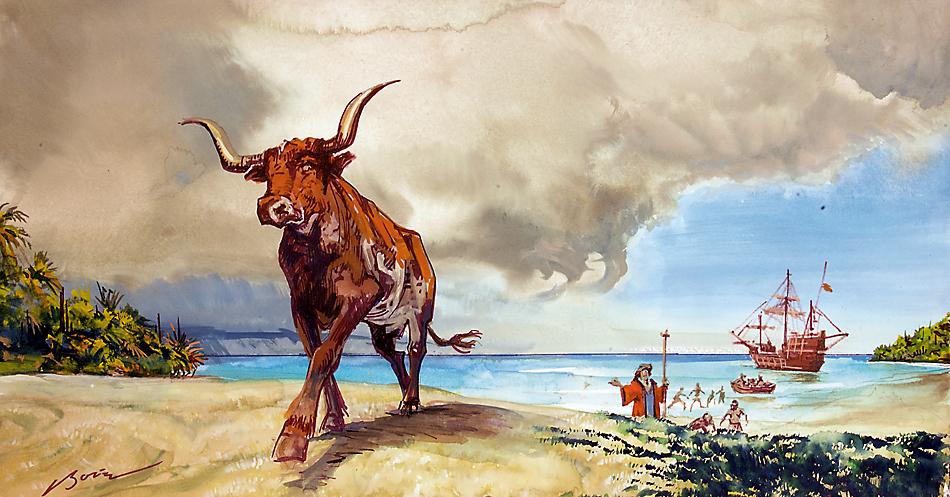

On November 27, 1493 the first Spanish longhorn stepped onto the beach at Hispanolia in the New World. The arrival of cattle and horses signaled a sea change that would sweep across North and South America and lead directly to the American Cowboy.