There are two sides to every story, and the greatest thing about the Black Hills of South Dakota and Wyoming is that you can hear and see both sides.

Well, maybe that’s not the greatest thing. I mean, there’s Devils Tower National Monument … oh, and Custer State Park … wait, let’s not forget Deadwood and its wonderful Adams Museum (plus all those casinos to take your hard-earned money). It’s hard to top Lintz Bros. Pizza in Hermosa … and, wait, didn’t “The Star-Spangled Banner” kinda begin at Fort Meade in Sturgis? … and how can we leave off Mount Rushmore? Or, since we’re talking about those two sides, the Crazy Horse Memorial?

Wow. I’m already exhausted, and I’m only in Sundance.

Sundance Kid, Bad God’s Tower & a Buffalo Jump

This Wyoming town on the edge of the Black Hills is a good jumping-off point. Stop in at the Crook County Museum & Art Gallery in the lower level of the county courthouse. Harry Longabaugh, better remembered as the Sundance Kid, spent a little time here for stealing a horse. You can even sit in a spectator chair from his trial for that crime. Then you should check out the dioramas showcasing Devils Tower, George Custer’s 1874 expedition into them thar hills and the Vore Buffalo Jump.

From Sundance, we might as well loop over to Devils Tower. Established by President Theodore Roosevelt on September 24, 1906, as the nation’s first national monument, this rock shoots dramatically 1,267 feet to an elevation of 5,112 feet. Devils Tower got its name in 1875 during Col. Richard Irving Dodge’s expedition when an interpreter misinterpreted the name as Bad God’s Tower. The Lakota called it “Bear Lodge” or “Brown Buffalo Horn,” while other tribes—Arapaho, Crow, Cheyenne, Kiowa, Shoshone—had their own names for it. And, of course, it was the star in 1977’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

Yes, climbing is allowed. Me? I’ll stick to hiking, specifically, on the 1.3-mile Tower Trail. It’s paved.

From here, backtrack to I-90 and make a stop at the Vore Buffalo Jump east of Beulah. At least five tribes used this site over a 300-year period to harvest perhaps 20,000 buffalo—I mean, bison. For archaeologists, this is definitely a work-in-progress. Only about five percent of the site has been excavated.

We’ll get to more diggings and buff—er, bison—once we cross the state line into South Dakota. But now it’s time for two sides of history.

The Two Faces Behind the Black Hills

The Black Hills (Pahá Sápa, to the Lakota) belong to the Lakota, according to the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868. Then George Custer led an expedition into the hills in 1874. Gold was discovered in French Creek, and, before you could say “Calamity loves Wild Bill,” the rush was on.

South Dakota’s Deadwood, Lead (as in “I lead,” not “I’m slow as lead”), Hill City, Custer City and Rapid City were soon born. This led to the United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians, a 1980 Supreme Court decision that said the Black Hills were illegally taken from the Lakota by the U.S. government and that the U.S. owed the Indians almost $106 million in remuneration. That figure has gone up astronomically over the past 32 years. The Lakota still won’t take it.

Sometimes I can’t help but feel like a dirty squatter when I find myself in this beautiful country.

Want two sides to the story?

For the first part, stop at Sturgis, where the Old Fort Meade Museum pays tribute to the Army presence in the Black Hills. Established in 1878, Fort Meade was first manned by the reformed 7th Cavalry after the Little Big Horn battle. Comanche, the legendary horse of Little Big Horn fame, was officially retired here. It was also here that, in 1892, Col. Caleb Carlton ordered that “The Star-Spangled Banner” be played as the finale for all concerts and parades. That song wouldn’t officially become our national anthem until 1931.

That’s one part of this story. Bear Butte State Park has another side. The Lakota called this rock formation Mathó Pahá, and the Cheyenne named it Noahvose. It was holy to these Indians long before the whites came, and it remains sacred to many tribes. That’s why, when you visit, you may find prayer cloths and tobacco ties left behind. Respect these. You can learn more about the Indians’ beliefs at the park’s education center.

Actually, there’s a third story here, and if you’re around for the 72nd Annual Sturgis Motorcycle Rally (August 6-12), be careful what you say about Harleys.

South Dakota’s “Cool” Spots

Continuing on, I’ve always wondered why Rapid City isn’t the capital of South Dakota (I mean, really, have you been to Pierre?). Rapid City has art (Dahl Arts Center). It has culture (Black Hills Symphony Orchestra). It has the excellent Prairie Edge Trading Company & Galleries, and a lot of history (The Journey Museum). Mount Rushmore has only four presidents, but Rapid City has life-sized bronze statutes of a bunch of them (Hey, Reagan’s donning a cowboy hat).

It’s time to travel south. Kids will likely enjoy Evans Plunge down in Hot Springs. The pool was built in 1890 and named after its founder, Fred Evans. There’s another story here too. The Lakota and Cheyenne also enjoyed this natural river as far back as the early 1800s, long before Col. W.J. Thornby claimed the spring in 1876 and sandstone architecture began dotting the landscape.

A cool story can be found at Black Hills Wild Horse Sanctuary. Thanks to Dayton O. Hyde, who founded this preserve in 1988, hundreds of wild mustangs can live free and roam across 11,000 acres. Hyde, well into his 80s and still active in the sanctuary, has a pretty good story himself. An Oregon rancher, he became obsessed with saving wild horses, raised enough money for a down payment on some land and persuaded the Bureau of Land Management to send him unadoptable wild horses.

Of course, I mentioned there would be some more digging in these hills. See for yourself at the Mammoth Site in Hot Springs, an active paleontological dig site and the world’s largest mammoth research facility. Trapped mammoths died at a spring-fed pond here some 26,000 years ago. In 1974, during excavation for a housing development, bones were discovered. Plenty of paleontology, geology, history and research stories happen here practically every day.

From Hot Springs, I head up to Wind Cave National Park. This complex series of caves—known for its boxwork formations that resemble honeycombs—began being explored in 1881, when brothers Jesse and Tom Bingham discovered the cave’s only natural opening. It became a national park in 1903. But there’s another story here too. Indians knew of this cave long before a 16-year-old boy named Alvin McDonald started exploring it in the 1890s. In fact, Lakota creation stories tell of a hole that blows air, and it was from this sacred site that the Lakota emerged from the underworld.

From Wind Cave, head up toward Custer and the sprawling, magnificent Custer State Park, established in 1912 as the Custer State Forest and Game Preserve. There’s likely no better place to see (whether on foot, horseback, bicycle, canoe or car) the wonder that is the Black Hills than in these 71,000 acres. You might spot wild burros or bighorn sheep, and, naturally, buffalo. The park is home to one of the nation’s largest bison herds, and the annual Buffalo Roundup in September is certainly worth watching.

Of course, maybe the best stories out of the Black Hills are those of Gutzon Borglum and Korczak Ziolkowski. Borglum arrived in South Dakota in 1924 and started work on Mount Rushmore in 1927, creating 60-foot sculptures of the heads of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln. The National Park Service took over in 1933 before the project was completed. When Borglum died just before his 74th birthday on March 6, 1941, his son, Lincoln, took over. Actually, the plan was to sculpt the presidents from heads to waists, but funding soon vanished, and the project stopped in October 1941. It’s still an impressive tribute.

Maybe even more impressive is Ziolkowski’s story. After hearing about Lakota leader Henry Standing Bear’s dream, “My fellow chiefs and I would like the white man to know that the red man has great heroes, too,” Ziolkowski began working on the Crazy Horse Memorial in 1948, to honor the culture, tradition and living heritage of American Indians. Ziolkowski died in 1982, but the project continues.

There’s more to do in Hill City and Keystone than look at massive sculptures, but at Crazy Horse Memorial and Mount Rushmore National Memorial, take your time. Both are amazing.

Then hop aboard the 1880 Train, a two-hour-plus round trip Hill City-Keystone steam excursion, and stop by the South Dakota State Railroad Museum, next door to the Hill City depot, to hear the state’s railroad stories since 1872. Take a horseback ride at High Country Guest Ranch near Hill City. You can even sample wine—mostly South Dakota fruit wines such as Red Ass Rhubarb (I’m not making this up)—at Hill City’s Prairie Berry Winery.

Then it’s on to Deadwood.

The Neverending Story

Millions of stories populate this naked city. Many can be found—or are waiting to be found—at the magnificent Adams House, the Adams Museum, the Homestake Adams Research and Cultural Center, and the Days of ’76 Museum, all under the oversight of the new Deadwood History Inc. But don’t overlook Mount Moriah Cemetery, the final resting place of Wild Bill Hickok, Calamity Jane, Seth Bullock and other Old West icons.

You’ll also find a story at Tatanka: Story of the Bison, a center anchored by Peggy Detmers’s larger-than-life sculpture of 14 bison pursued by three Indians on horseback. The story behind this sculpture involves more than just the history of Lakota and the bison. Detmers sued actor and Tatanka founder Kevin Costner (yep, from Dances With Wolves) for breach of contract in 2009, but last summer a judge ruled that Costner had met the terms of the contract.

Sigh, even in a place as wonderful as the Black Hills, there are those kinds of stories.

I bet, however, that if I took this road trip again, I’d discover many more stories. Pleasant stories. Beautiful stories. Tragic stories. Stories with more than one side.

Johnny D. Boggs advises travelers not to badmouth the Boston Celtics at Lintz Bros. Pizza.

Photo Gallery

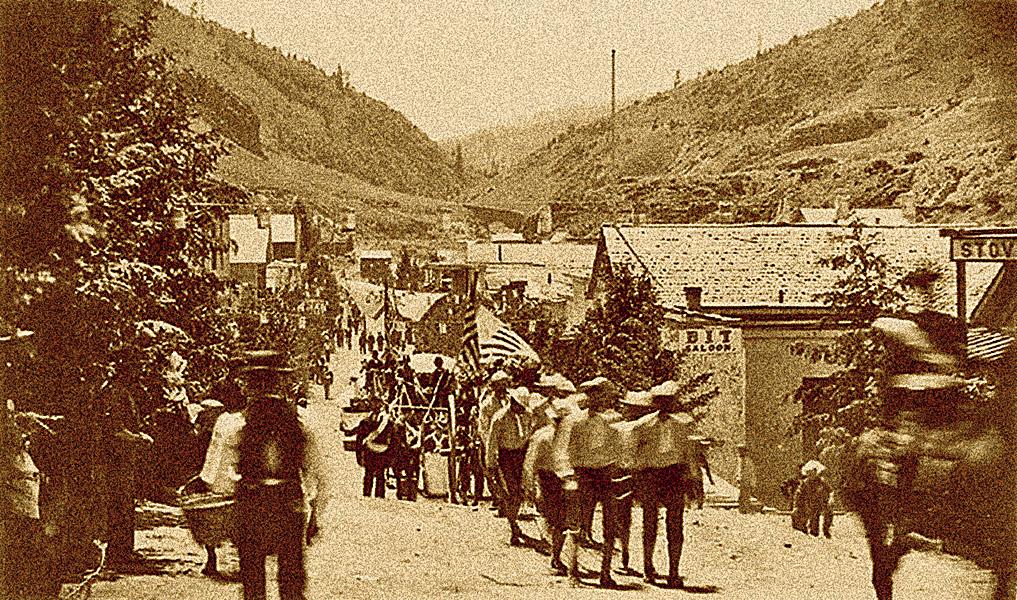

The 1862 gold town of Canyon City, Oregon, has a long history of celebrating the Fourth of July. The Independence Day parade, shown above in 1885, is such a big part of the town’s pioneer history that artist Larry Kangas included an 1890s Fourth of July parade for his mural project painted on century-old buildings. You can see that mural on a building at the north edge of Canyon City’s park near City Hall.

– All images True West Archives –

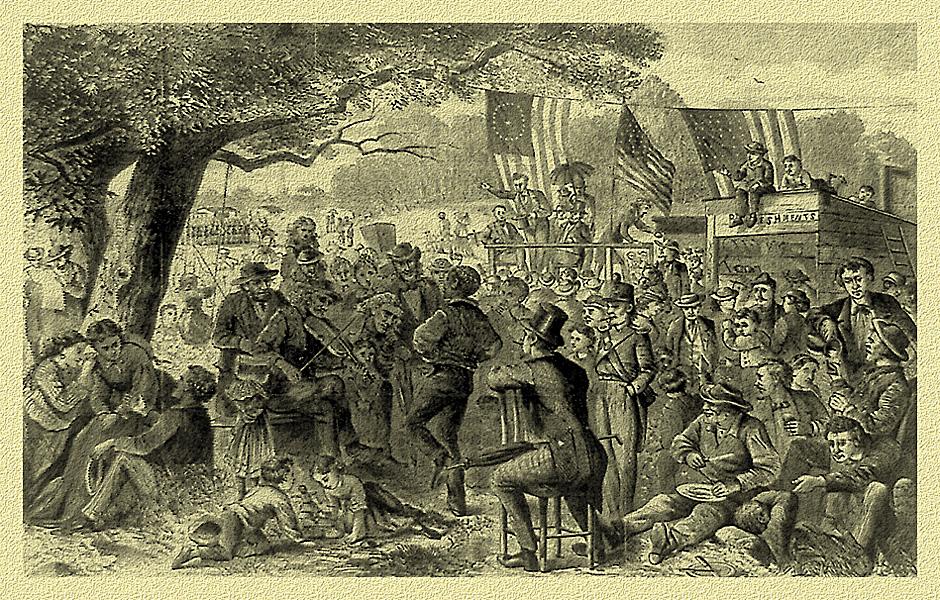

This patriotically-dressed girl stands with America’s flag on July 4, 1906, at the Fort Belknap Reservation in Montana. During this week-long Fourth of July celebration, the Gros Ventres and Assiniboines celebrated the Sun Dance by participating in grass dances, sham battles and horse races.

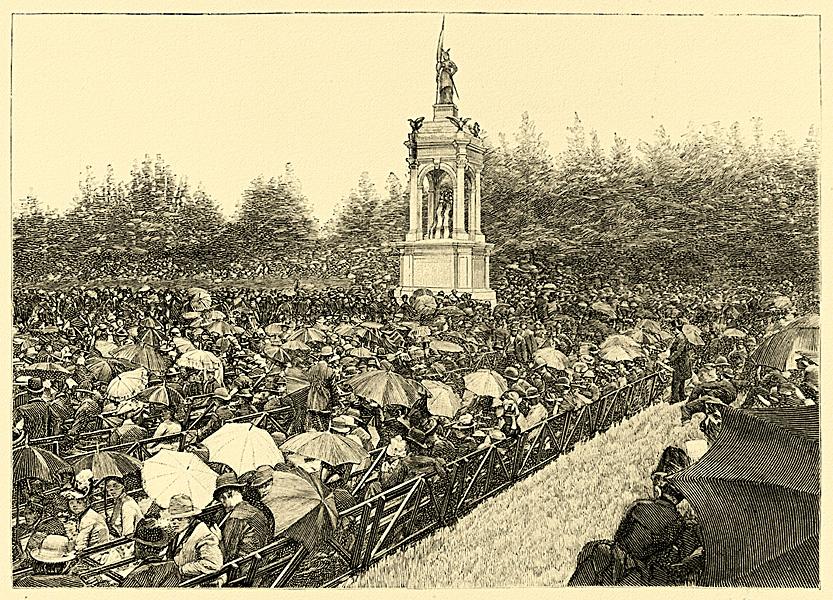

San Francisco celebrated its Fourth of July in 1888 by unveiling the nation’s first memorial to Francis Scott Key who penned the lyrics for “The Star-Spangled Banner.” The monument was placed in the city’s Golden Gate Park 43 years before the song became our national anthem.