A university student had argued that Geronimo was an alcoholic, a habit that likely caused some of the problems faced by the Apaches. The professor, who believed this statement disqualified the paper and had wanted to reject it, was outvoted by two others who accepted it.

As I was serving on a panel at Arizona’s Tucson Book Festival in 2009 that addressed various topics related to the history of the Apache, he raised his hand and asked me to comment.

I said, “Sure, they were all drunks.”

That bit of flippancy jarred the audience.

I tried to explain the concept of tiswin, but did not do a very good job. I had violated a code of modern political correctness. The answer, of course, was insensitive, but it contained an element of truth. Last year, I returned to the book festival to provide a better answer to the question, which I share here with you, as well.

A Respected Apache Voice

Jason Betzinez, a graduate of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, was a highly respected Apache voice whose book, I Fought with Geronimo, contains much information that can be cross-checked with other sources and determined reliable. Quoting this native voice: “Apaches possessed many virtues such as honesty, endurance, loyalty, love of children, and sense of humor. They also had at least two serious faults. One of these was drunkenness and the other a fondness for fighting among themselves, these often going hand in hand.”

Literature about Apaches is heavy with references to “tiswin drunks.” For centuries, tiswin was a theme running through Apache culture and tradition. Mildly intoxicating in its basic composition, it figured in most Apache ceremonial and social occasions. In this form, tiswin could hardly produce a drunk, only a buoyant feeling appropriate for such gatherings. But manipulation of ingredients could result in an intoxicant powerful enough to produce a tiswin drunk. As Betzinez remarked, Apaches loved to fight among themselves, and a tiswin drunk provided a good setting.

Tiswin was beer brewed from corn. The corn was shelled, soaked in a can of water, spread out on a blanket or other fabric in the sun until it sprouted, then ground into a meal and poured into a can of boiling water. When half the water boiled away, it was replenished and brought to a boil again. The water was then strained, cooled and poured into another can or barrel, and allowed to stand until it sent up bubbles. This was tiswin in its most rudimentary form, but it rarely emerged in its most rudimentary form. Women made the tiswin, and each had her own recipe, in which she manipulated the ingredients and added others. Her recipes were her secret, and some women rose to high status as expert makers of tiswin. Such were the two wives of the Chiricahua chief Mangas, Huera and Francesca (or maybe they were the same woman). In the hands of skilled women, tiswin could range from mild to powerful and sour to savory.

Note that Betzinez did not specifically mention tiswin; he said drunkenness. Apaches made other intoxicants, including several derived from the baked head of the agave plant, most notably mescal and tequila. The agave, or century plant, also yielded juice from which to ferment pulque, one of the most potent intoxicants. Then the Americans brought whiskey, and Apaches sought any they could obtain.

Many of what Americans called tiswin drunks were powered by other varieties of alcohol. Corn was not all that plentiful. Whether drinking tiswin or another intoxicant, drunks formed a prominent feature of Apache tribal history and the history of Apache relations with Americans.

Mexicans, the primary targets of Apache raids, quickly recognized the Apaches’ insatiable craving for alcohol. More ruthless than Americans, Mexicans employed that thirst to their advantage. Time and again they lured groups of Apaches into towns or villages to trade, then freely dispensed mescal or other alcohol, and massacred drunken Indians. The Apaches well knew this ploy and its consequence, but they repeatedly fell for it.

Geronimo’s Tragedy

Geronimo himself furnishes a prime example as a target who fell for the trick. Following a successful raid into Sonora early in 1851, some of the raiders crossed the Sierra Madre to Janos, Chihuahua, where rations could at times be obtained. As revenge lay at the heart of Apache war-making, so did it motivate Mexicans. Sonoran Col. José María Carrasco and about 400 guardsmen and militia crossed the Sierra Madre from Sonora into Chihuahua and crept up on Janos without discovery by either Apaches or the Janos authorities.

On March 5, 1851, the militia struck, destroying several of the Apache rancherías. Carrasco reported killing 16 warriors and five women, and taking 62 captives. Of these, 56 or more were women and children—herded off with his command to be sold into slavery.

Geronimo recounted his own experience: “Late one afternoon when returning from town we were met by a few women and children who told us that Mexican troops from some other town had attacked our camp, killed all the warriors of the guard, captured all our ponies, secured our arms, destroyed our supplies, and killed many of our women and children. Quickly we separated, concealing ourselves as best we could until nightfall, when we assembled at our appointed place of rendezvous—a thicket by the river. Silently we stole in one by one: sentinels were placed, and, when all were counted, I found that my aged mother, my young wife, and my three small children were among the slain. There were no lights in camp, so without being noticed I silently turned away and stood by the river. How long I stood there I do not know, but when I saw the warriors arranging for a council I took my place.”

That tragedy burned into Geronimo a lifelong hatred of Mexicans, whom he would kill as many and as often as he could.

Drinking with Crook’s Men

To cite an instance in which a tiswin drunk indisputably led to a significant historical consequence, let’s go to the early 1880s, when Gen. George Crook ruled the Chiricahuas on the White Mountain Reservation in Arizona. They had been settled near Fort Apache and placed under charge of Lt. Britton Davis. The Chiricahuas liked and respected Crook, with two qualifications. One was his rule against the custom of a man beating a wife for any offense and for cutting off her nose as punishment for adultery. The other was Crook’s insistence on banning tiswin. Both had long been traditional in Apache culture, and the Indians strongly resented any interference with them. They emphatically informed Davis of their attitude. Even though he had the duty of enforcing these rules, by persuasion, reprimand or even jail time, the Chiricahuas continued to do as they pleased.

The issue climaxed on the morning of May 15, 1885. Davis awoke to discover most of the Chiricahua leaders drawn up in front of his tent. The chiefs and Geronimo, who was a medicine man, had come to talk. Davis invited them inside, where they squatted in a semicircle. Four, including Geronimo, were intoxicated; another four were badly hung over. Old Nana angrily addressed the interpreter: “Tell the Nantan Enchau [Stout Chief] that he can’t advise me how to treat my women. He is only a boy. I killed men before he was born.”

Chief Chihuahua, “palpably drunk and in an ugly humor,” quickly got to the purpose of the meeting. “We all drank tiswin last night, all of us in the tent and outside, except the scouts; and many more. What are you going to do about it? Are you going to put us all in jail? You have no jail big enough even if you could put us all in jail.”

The lieutenant replied that this issue was too important for him to resolve, that he would have to telegraph Gen. Crook for a decision. The telegram had to go through Davis’s superior at San Carlos, Capt. Francis Pierce, to reach Crook in Prescott. On the advice of his chief of scouts, Al Sieber, himself sleeping off a hangover, the captain pigeon-holed the telegram.

As the days passed without an answer, Davis grew increasingly anxious and the Apaches increasingly suspicious of bad faith. At dusk of May 17, 144 men, women and children packed up and hurried south, headed for the strongholds of Mexico’s towering Sierra Madre. Although 400 remained, the breakaways launched the last conflict between the U.S. Army and the Apaches. Tiswin had clearly played a vital role in the outbreak.

Hung Over at Canyon

of the Funnels

Tiswin played no part in another incident of drunkenness. Here, the culprits were whiskey and mescal. The reservation outbreak triggered by tiswin led Gen. Crook to field columns of Apache scouts to try to dig the errant Chiricahuas out of their recesses in Mexico’s Sierra Madre. After months of maneuver and pursuit, the exhausted breakaways told Lt. Marion P. Maus they wanted to talk with Gen. Crook. For their meeting, they designated a steep ravine just south of the boundary called Cañon de los Embudos. Both Maus and his scouts and Geronimo and his followers met there in March 1886. Geronimo and his followers took an impregnable position, while Maus’s scouts camped below.

Although expected daily, Crook had not arrived. Another white man had, a beef contractor named Charles Tribollet, who erected a small shanty at San Bernardino, below the border, and dispensed whiskey and mescal. The scouts quickly discovered Tribollet, and even as the Chiricahuas settled into their positions, Maus’s camp rocked with wild debauches. The Chiricahuas lost no time in locating Tribollet, and for three days, until Crook belatedly appeared, both scouts and Chiricahuas indulged in raucous drunks. By this time, they were all badly hung over and the Chiricahuas in a foul mood.

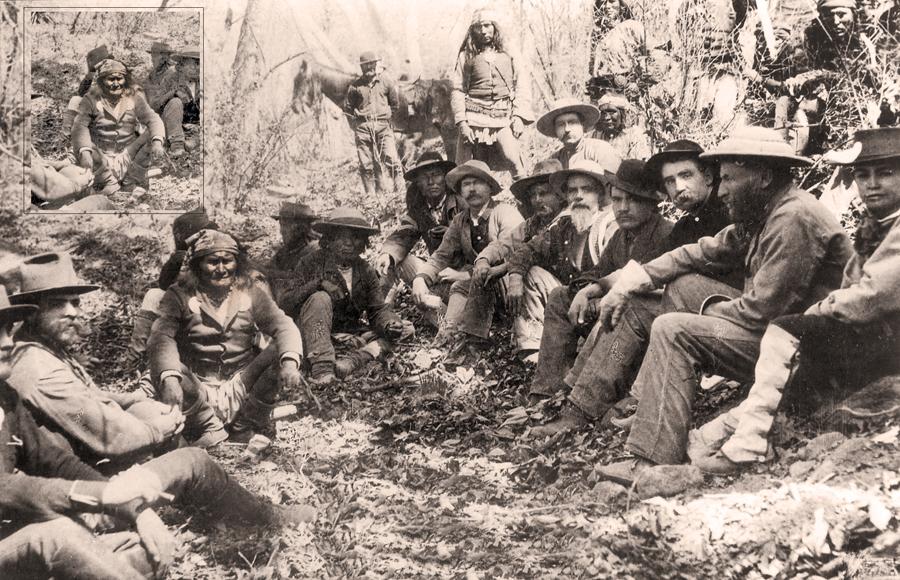

In a half-circle, Geronimo, Naiche, Crook and a few officers and civilians sat on one side at the bottom of a ravine shaded by cottonwood and sycamore trees. Crook had resolved to be firm and dictatorial, not the best approach for hung over Apaches. Crook “talked ugly” and angered and humiliated Geronimo. He and his people wanted simply to go back to the reservation, which Crook could not grant; he demanded unconditional surrender. That night, he infiltrated his own Apache agents into the infuriated stronghold, but even they made no progress until tempers cooled. Only then did the breakaways agree to give up, but, except for Chief Chihuahua and his people, not unconditionally. Crook had to grant terms: exile to Florida for two years before coming back home.

The Chiricahuas remained in their fortress all night, except to ride to Tribollet’s shanty. Returning at daylight, widely scattered and reeling drunkenly, Geronimo and a few others met Crook and his staff moving back to the boundary. Lieutenant Maus and his scouts remained in camp, waiting to escort the Chiricahuas to Fort Bowie. They had no intention of being escorted. They gathered in their defenses and continued to drink through the night, constantly firing their rifles. Naiche got so drunk, he shot and wounded his wife.

The next morning Maus’s scouts got them moving. They moved, but in a random, dispersed body, firing their rifles. Five miles up the valley they came together to meet Maus, all still drunk. They told him they would come in as soon as they were sober. By nightfall, five miles farther, they settled into a camp near Maus’s.

Although the army had destroyed Tribollet’s shanty and all its contents, Geronimo and Naiche had retained enough to get drunk two nights later. After midnight the two leaders gathered 20 men, 13 women and two children, and slipped away from their camp, headed back for the Sierra Madre. Remaining with Maus were Chihuahua and his people who had surrendered unconditionally.

Crook yielded his command to Gen. Nelson A. Miles, who had to campaign another five months to bring Geronimo and Naiche to terms. Crook bears much of the blame for what went wrong at Cañon de los Embudos. But Apache drunkenness—and not tiswin-fueled drunkenness—is an influential theme that runs throughout this episode.

These are only a few of many examples of what the native voice of Betzinez labeled Apache drunkenness. Two years ago, I blamed tiswin, which was partly to blame, but probably not as much as other alcoholic beverages.

And what of the Army officers who chased the Chiricahuas? I can’t say that they all were drunks, but most of them were.

Robert M. Utley is a former chief historian of the National Park Service and the author of 17 books on the history of the American West. He will give a lecture on Geronimo at the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona, this fall. His Geronimo biography is due out from Yale University Press in November 2012.

Photo Gallery

In celebration of Arizona’s 100th birthday of statehood, the Heard Museum in Phoenix has a year-long exhibit, “Beyond Geronimo: The Apache Experience.” The exhibit features sculptures by Allan Houser, the first Chiricahua Apache child born out of captivity, as well as family heirlooms. It also showcases numerous historical photographs of Geronimo and other Arizona Apaches, including this one of Alchesay and other scouts who helped Crook track down the Chiricahuas. Notice the red bandanas; Crook had his scouts wear these so his men could distinguish them from the enemy Apaches.

– Courtesy Arizona Historical Society/Tucson, #50082 –

– True West Archives –