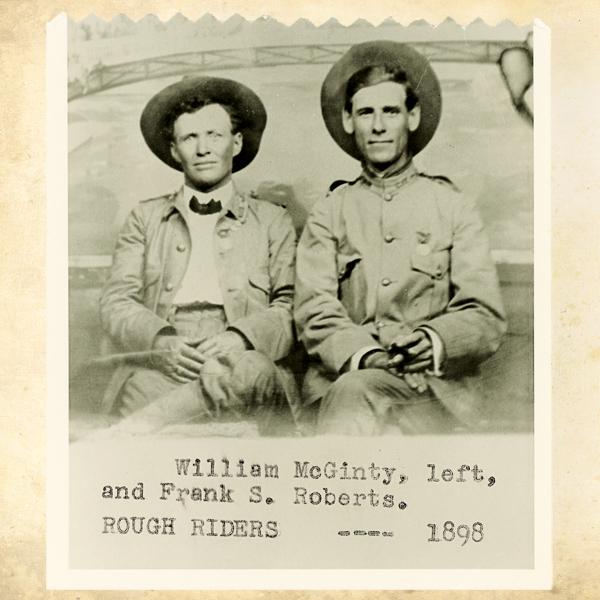

Billy McGinty was an unlikely hero. Only five feet, two inches tall, the sawed off bronc buster from Oklahoma Territory couldn’t march in step and was allergic to military discipline, but he turned out to be one heck of a fighting man. McGinty distinguished himself as a trooper with the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry—Rough Riders—during the Spanish-American War of 1898. Teddy Roosevelt said of McGinty, “we had no better or braver man in the fights.”

Billy McGinty was an unlikely hero. Only five feet, two inches tall, the sawed off bronc buster from Oklahoma Territory couldn’t march in step and was allergic to military discipline, but he turned out to be one heck of a fighting man. McGinty distinguished himself as a trooper with the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry—Rough Riders—during the Spanish-American War of 1898. Teddy Roosevelt said of McGinty, “we had no better or braver man in the fights.”

Born in Missouri in 1871, McGinty revolved his life around horses. At 14, he left home to work as a ranch hand near Dodge City, Kansas. He earned a reputation as someone who could ride any horse, no matter how mean or wild, and he worked for cattle operations in Indian Territory, Texas and Arizona. In 1897, when his father died, McGinty moved to Ingalls, Oklahoma Territory, to take care of his deceased father’s horses and ranch.

When the Spanish-American War started in April 1898, McGinty, seeking adventure, rushed to join the U.S. Army. Wanting to enlist on the first day, he rode all night from Ingalls to Guthrie. The outfit McGinty joined was quickly forming for battle, meaning officers had little time for training and were looking for recruits who already knew how to ride and shoot. McGinty fit this mold. His fellow troopers, recruited largely from Arizona, New Mexico and Oklahoma Territories, were a rough and tumble band of cowboys, miners, hunters, Indian fighters, law enforcement officers and the like. All in all, they made up a formidable, if irregular, fighting regiment.

The exception to this Wild West background was a cadre of elite Easterners, mostly friends of Roosevelt’s and graduates of Ivy League colleges. These intrepid young adventurers were uniformly athletes—football players, track stars, yachtsmen, polo players and champion rowers. Many were scions of prominent families, and a number would go on to success on Wall Street and in the business world, while others would die in Cuba.

The commander of the regiment, Col. Leonard Wood, had fought the Apaches in Arizona. During the fighting in Cuba, Wood was promoted to brigadier general and Roosevelt became colonel.

McGinty and the Oklahoma recruits were transported by train from Guthrie to San Antonio, Texas, where the officers tried to instill military discipline into their troops. In McGinty’s case, this didn’t come easily. Not able to remember officer’s ranks, he called them all “Boss.” His attempts at marching, perhaps because of his short legs, were comically unsuccessful. During one chastisement for not keeping step, he responded that he was “pretty sure he could keep step on horseback.” The Rough Riders being a cavalry unit, he was soon given his chance.

For this 1,000-man regiment, the Army acquired more than 1,200 horses. Most of the horses were rough stock, “plenty mean,” McGinty remembered. Given the wildness of the horses, McGinty and four other cowboys were assigned as bronco busters for the unit.

The Rough Riders didn’t stay long in San Antonio, as the U.S. was anxious to rush troops into Cuba. On May 28, less than a month after training began, the regiment was moved by train to Tampa Bay in Florida. In Tampa, the troops began to fully understand the country’s levels of unpreparedness for war. Tampa did not have enough transport ships to carry all of the troops to Cuba. Only about half of the Rough Riders obtained transport, and none of the enlisted men’s horses made the trip. Thus, they would fight on foot during the Cuban campaign.

Due to Woods’s foresight, the men were at least properly armed with smokeless Krag-Jorgensen carbines. Some of the other volunteer units were not so fortunate, as they carried Civil War-era rifles that let off dark smoke when fired, revealing the location of the shooter and making for an easy target for the Spaniards who were armed with smokeless Mausers.

The regiment was also equipped with four Gatling guns, which had been donated by wealthy friends of Roosevelt’s. The Gatling guns proved invaluable in the battle at San Juan Heights.

The Rough Riders, along with about 5,000 other regular Army and volunteer units, disembarked in Daiquiri on the southwest coast of Cuba on June 22 to begin their journey through the jungle toward Santiago. On the march, they joined with more forces, making up an army of 12,000 men. The goal was to take the Spanish fort in Santiago and drive the Spanish fleet out of Santiago harbor into the path of the U.S. fleet, which was waiting off the coast of Cuba.

As the troops marched, they faced a hostile tropical environment. Extreme heat accompanied exposure to yellow fever, malaria and dysentery. The conditions, along with casualties inflicted by the Spanish, caused the deaths or disabilities of nearly one third of the force.

Not much time passed before the troops encountered the enemy. On June 24, U.S. forces made contact with the rear guard of the Spanish Army near Las Guasimas. McGinty, like his mates, saw his first fighting in Las Guasimas. The first Rough Rider to engage the enemy was Tom Isbell, a Cherokee from Muskogee. Isbell sighted a Spanish soldier through the thick jungle and shot him, which elicited a barrage of fire from other Spaniards. Hit seven times, Isbell remarkably survived. The Spanish inflicted a toll on the Rough Riders of eight killed and 34 wounded.

The Rough Riders then moved toward San Juan Heights, a series of hills, including San Juan Hill and Kettle Hill, which guarded the approach to Santiago. On these hills, across the San Juan River, the Spanish had set up their defenses, comprised of lines of trenches and backed by an artillery unit.

On July 1, U.S. troops lurched forward down the only road through the jungle. Part of the forces planned to attack El Caney to the north and then rejoin the assault on San Juan Heights. When some 5,000 troops got pinned down in the taking of El Caney, they could not participate in the assault on San Juan.

The Rough Riders advanced about 500 yards from the Spanish defenses, where they came under a relentless fusillade from the Spanish infantry and a continuous bombardment from the Spanish artillery. For several hours, U.S. troops were shot to pieces as they awaited orders to advance. The crossing at San Juan River was so dangerous, it became known as “Bloody Ford,” and the entire area was called “Hell’s Pocket.” Roosevelt and the other field officers finally exercised the only available strategy and attacked.

The Rough Riders, along with two regiments of dismounted black cavalry, surged toward Kettle Hill. With Roosevelt in the lead, riding his horse Little Texas, the soldiers fought their way through the high jungle grass and then labored up the steep incline toward the Spanish trenches. Still under withering fire, the troops suffered more casualties. The irregular advance finally grouped near the top and rushed the Spanish trenches, killing some of the enemy in hand-to-hand combat at the top of the hill and driving the Spaniards into retreat.

At the same time, U.S. forces were attacking San Juan Hill to the left. Both onslaughts were successful only because of the covering fire laid down by the Gatling guns, which raked the enemy positions with deadly accuracy. This was the first time in military history that automatic weapons were used to support an attack, rather than as strictly defensive weapons.

The charge up San Juan Hill would immortalize the Rough Riders in history and vault Roosevelt into the public eye, helping to launch a political career that resulted, ultimately, in his presidency. The charge is often portrayed as though the troops had rushed forward in an orderly formation, much like a football line surging against an opponent. In fact, their advance was more ragged, through deep jungle grass and across steep terrain. Under these brutal and dangerous conditions, the Rough Riders and their black counterparts came under heavy fire for a long time.

McGinty pressed forward, even as soldiers fell wounded or dead around him. He proved his bravery and never faltered in the attack. His real heroism, however, took place in the next round of fighting.

The Rough Riders were ordered to defend Kettle Hill. That afternoon and night, they repulsed a counterattack by the Spanish. In defending their position, some of the troops dug a shallow trench on the downslope of the hill facing the Spaniards, who were defending a line closer to Santiago. From their forward position, the troops were exposed to fire from the Spanish and could not proceed back up the hill in daylight.

Roosevelt, realizing that the Rough Riders in the trench needed food and water, discussed the problem with another officer. McGinty, who overheard the conversation, said, “I’ll do it,” grabbed a case of food and launched himself over the crest of the hill.

As McGinty stumbled and ran down the hill, bullets from the Spanish flew around him. He tumbled into the trench unhurt, although two Spanish bullets had shot holes through the case of food. McGinty stayed in the trench until darkness, when the troops were able to crawl up the hill to safety.

The victory at San Juan Heights achieved its military purpose when the Spanish fleet fled the harbor on July 3 and was annihilated by the superior U.S. fleet. The siege of Santiago, however, continued through July 17, when the Spanish surrendered. This victory on land and sea, coupled with Adm. George Dewey’s triumph over Spain’s Pacific fleet in a battle near the Philippines, forced an early end to the war in August.

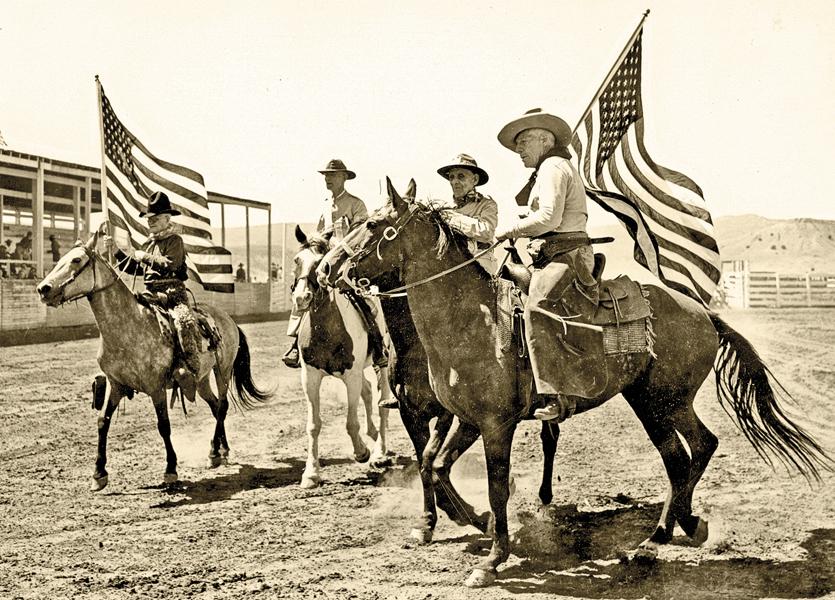

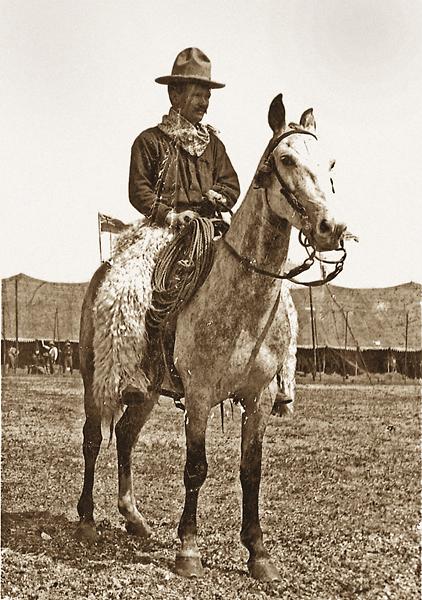

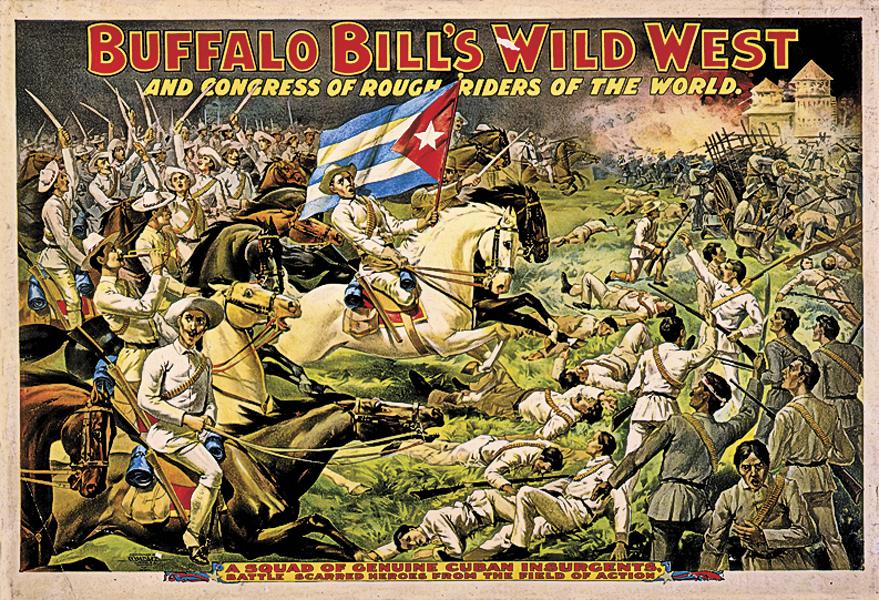

After the war, McGinty still craved adventure. He joined Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show and toured the world, riding bucking broncos and participating in re-enactments of the Battle at San Juan Heights. In 1902, he returned to Ingalls, Oklahoma, where he lived and ranched until his death in 1961. He also helped organize and lead Billy McGinty’s Country Band, the first nationally known cowboy band in America.

Kent F. Frates is an attorney and writer in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. He is the author of five books and numerous historical articles.

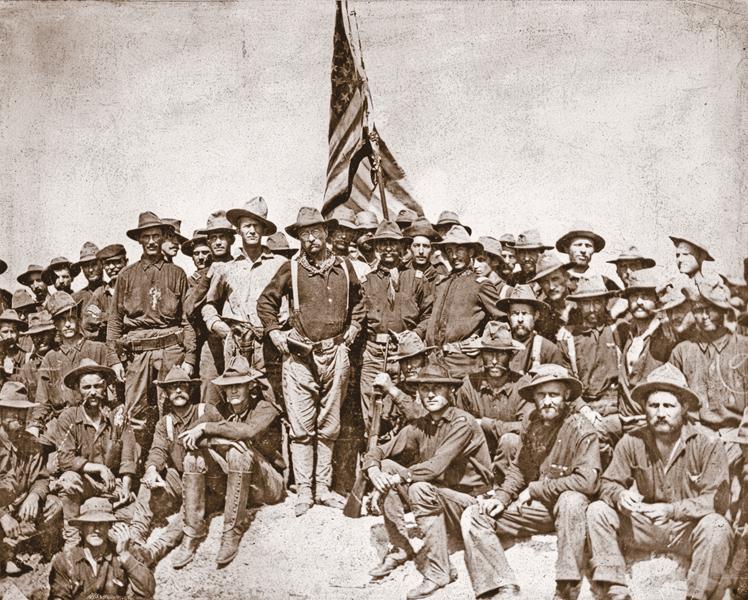

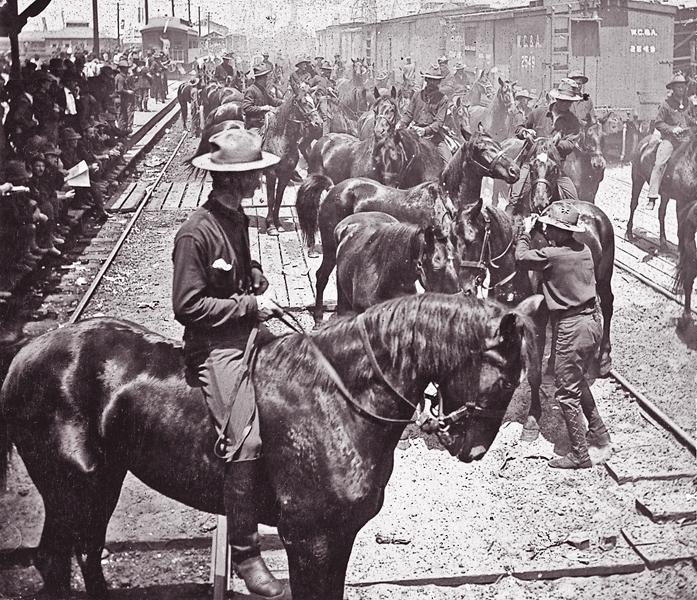

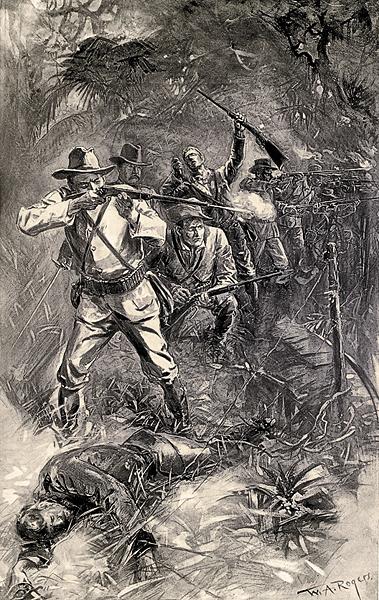

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Rough Rider Archive, City of Las Vegas Museum and Rough Rider Memorial Collection, Las Vegas,

– Courtesy Rough Rider Archive, City of Las Vegas Museum and Rough Rider Memorial Collection, Las Vegas, New Mexico, 2011.2.550 –

– Courtesy Washington Irving Trail Museum –

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– Courtesy Rough Rider Archive, City of Las Vegas Museum and Rough Rider Memorial Collection, Las Vegas, New Mexico, 61.1.177 –

– Courtesy Library of Congress –