One frontiersman, threatened with a .22 derringer, slapped it out of his assailant’s hand and said, “If anyone ever shot me with a twenty two…and I found out about it, I’d skin him alive!”

One frontiersman, threatened with a .22 derringer, slapped it out of his assailant’s hand and said, “If anyone ever shot me with a twenty two…and I found out about it, I’d skin him alive!”

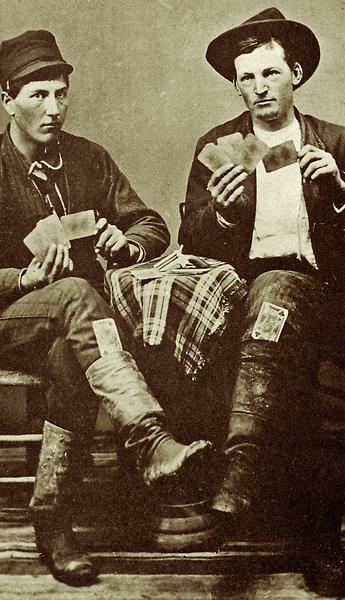

Despite comments like his, that reflect the abhorrence most Westerners felt toward small-bore firearms, hideout pistols could frequently be found concealed upon the persons of frontier folk.

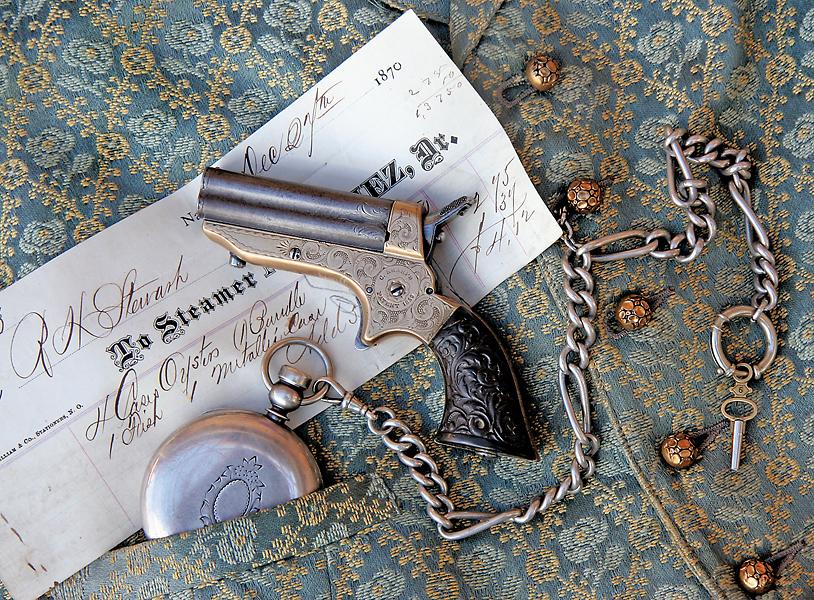

Slightly larger than a gentleman’s pocket watch, Sharps’s palm-sized Pepperbox derringer was a favorite with gamblers and others who felt they needed protection, but wished to keep their “ace in the hole” secreted out of sight.

Evidence of the practicality of this Pepperbox derringer is found in Grantley Berkeley’s own words, after being presented with one in the fall of 1859, when he was in St. Louis, Missouri. He remembered the pistol as “…the most perfect little bijou of a revolver I ever saw in my life… In size it is so small that I carried it in my waistcoat-pocket, and in execution so effective that at eight yards I could shoot as correctly, if not more so, than I could with my favourite pair of John Manton duelling pistols….”

C. Sharps & Co. (later in partnership with Sharps & Hankins), of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, manufactured the Sharps Pepperbox derringer, one of the more popular multi-shot derringers of the era. Although the firm patented this derringer in early 1859, the earliest examples of these arms appeared on the market in late 1858.

Until 1874, Sharps made more than 150,000 various models of its Pepperbox pistols. The British firm of Tipping & Lawden also produced approximately 6,000 of these, and a small amount were turned out by the Liege, Belgium firm of L. Ghaye—both under license.

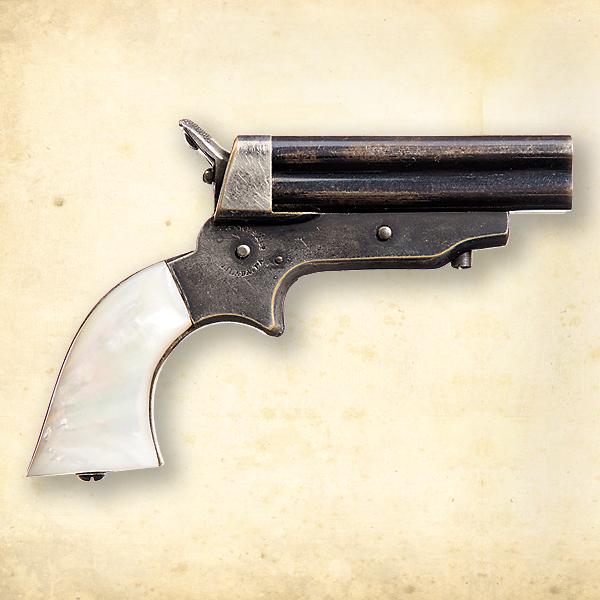

Regardless of which firearms firm produced the Pepperbox, the derringer had a square-shaped, four-barrel assembly that slid forward on the frame for loading and unloading. Depending on the model, the barrel release button could be found underneath the forward portion of the frame or on the side. After the shooter pressed the button, he simply slid the barrel forward. Unlike the older Pepperbox revolver design, in which the barrel rotated, Sharps’s design employed stationary barrels and a rotating firing pin, mounted either in the hammer or the frame, to fire each barrel in proper succession. A pivoting spring-loaded catch, which engaged a lug underneath the barrels, locked the barrels against the breech for firing. All of the Sharps Pepperboxes featured a standard blued barrel group and silver-plated frames for the brass-framed models and casehardening on iron-framed versions.

The most common model by far was the .22-caliber Model 1 with a total production of around 61,000 pistols. This palm-sized derringer measured just 47?8 inches overall with a 2½-inch long barrel assembly. Now known to collectors as the Model 1A, this Sharps has a straight-standing breech and is fitted with gutta-percha (early form of hard rubber) grips, rather than the wood stocks found on other models. The initial run featured serial numbers ranging from one to 60,000; when that was reached, numbering started over again at one. Sharps first produced its Pepperbox derringer in .22 short rimfire, then later in .30, and .32 short and long rimfire.

Today, despite being illegal to import replicas of this model into the U.S., the Sharps Pepperbox .22 derringer is the most copied American replica gun next to the Colt cap and ball revolvers. That is the sign of a true classic!

Phil Spangenberger has written for Guns & Ammo, appears on the History Channel and other documentary networks, produces Wild West shows, is a Hollywood gun coach and character actor, and is True West’s Firearms Editor.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Mowbray Publishing, Woonsocket, Rhode Island –

– Courtesy Phil Spangenberger Collection –

– Courtesy Rock Island Auction Company –