During the rough and woolly days of the 19th century lived a legendary generation of U.S. marshals whose real life exploits sound like a dramatic ballad.

During the rough and woolly days of the 19th century lived a legendary generation of U.S. marshals whose real life exploits sound like a dramatic ballad.

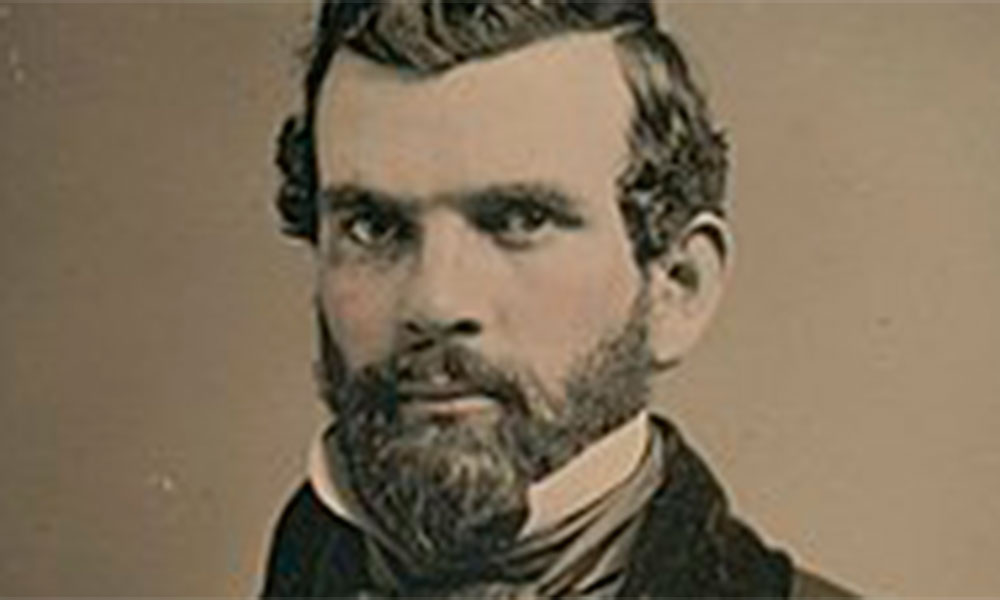

One young man, Paden Tolbert, born in 1862, chose to give up his quiet days as a schoolmaster and live the lonely and dangerous life of a frontier peace officer. In reputation and deeds, he would come to embody the agency’s motto: “Justice, Integrity and Service.” Working out of the U.S. District Court in Fort Smith, Arkansas, Tolbert covered western Arkansas and the incredibly rough Indian Territory of what is now Oklahoma.

For Tolbert and other deputy U.S. marshals, the challenge was not just in chasing the bad guys, but in fulfilling the job description that began at the founding of the nation.

When President George Washington established his administration and the new U.S. Congress began passing laws, a gap was inadvertently created: The federal government’s interests were not represented on a local level.

Congress’s response was to demonstrate the “long arm of the law” by establishing the U.S. Marshals Service with the Judiciary Act of 1789. These law enforcement officers were given extensive authority.

This was an era when the dispensing of justice was delivered personally, arriving after toting loaded guns, traveling cross-country on horseback to face uncooperative suspects.

Posse member Tolbert is remembered for one such arrival in the wilds of Cherokee Nation in 1892. Justice arrived that day in the form of a 16-man posse, a box of dynamite, a portable cannon—which Tolbert had traveled 225 miles round-trip to obtain—and a lot of determination. Their mission was to capture notorious outlaw Ned Christie, accused of killing Deputy U.S. Marshal Daniel Maples.

Christie had used a steam-powered sawmill to construct a fort in the mountains. With portholes on each side, the hideout—known as the “rabbit trap”—was nearly impregnable, having withstood earlier attempts to apprehend Christie.

When even the cannon failed to breach the structure, the posse waited until nightfall. They rigged a portable barricade from a charred rear wagon-axle bearing a wall of scrap oak timbers. Some posse members covered small-weapons fire for others who pushed the barricade close enough to ignite six sticks of dynamite at the hideout’s south wall. From inside, Christie and an outlaw partner fired continuously through second-story gun ports. The dynamite’s explosion finally opened the fort, but Christie survived the blast and stayed while fire destroyed much of his fort. Eyewitnesses said when he finally came out, he charged the posse, firing until he was shot down.

Tolbert toughed it out for 12 years in the U.S. Marshals Service, risking danger and delivering justice on the frontier. Afterward, he worked for Fort Smith & Western Railroad until his death in 1904.

Paden, Oklahoma, is the nation’s only town to be named for a deputy U.S. marshal. In nearby Clarksville, Arkansas, where Tolbert is buried, residents still remember his family introducing Elberta peach trees to the area. The fruit of descendant trees has brought renown to the area ever since.

Long before the Tolbert family immigrated to the New World to plant trees, they lived in Shropshire, England. The motto, “Ready to Accomplish,” on the family’s coat of arms proved prophetic for their ancestor, the determined lawman Paden Tolbert.

Tom Augherton is an Arizona-based freelance writer.

Do you know about an unsung character of the Old West whose story we should share here? Send the details : editor@twmag.com, and be sure to include high-resolution historical photos.