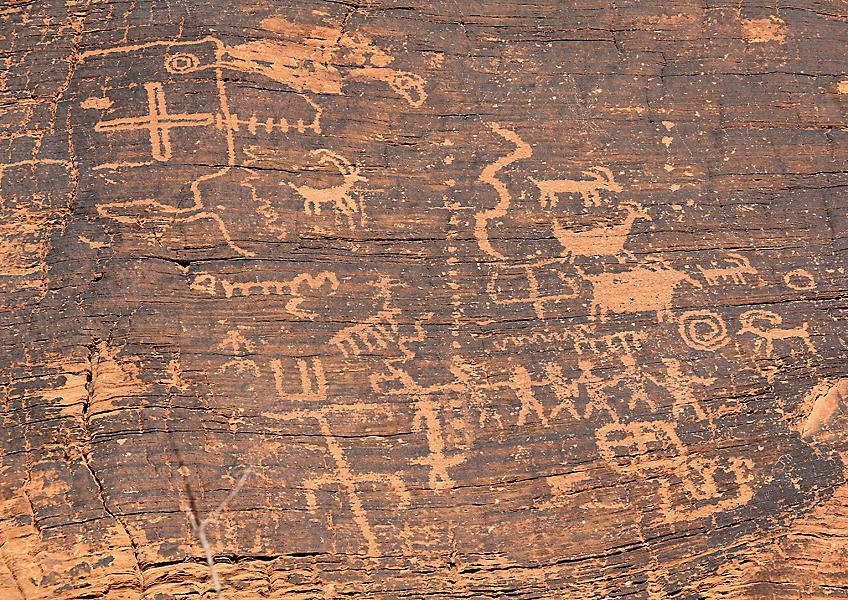

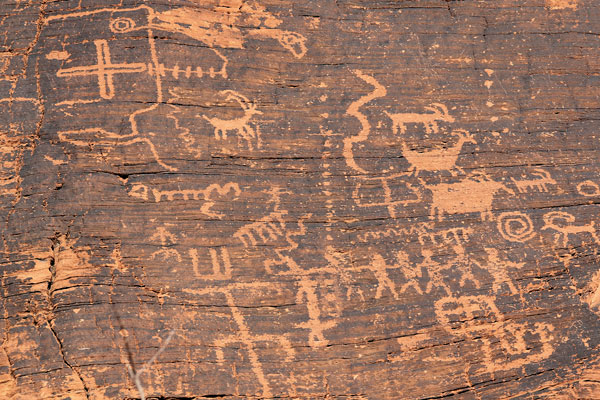

The tourists from Canada said they could not “read” the petroglyphs carved onto the rock walls at Valley of Fire in Nevada. “They don’t appear to be speaking Blackfoot,” the man told me as he inspected one of the carvings. He was joking, to a point.

The tourists from Canada said they could not “read” the petroglyphs carved onto the rock walls at Valley of Fire in Nevada. “They don’t appear to be speaking Blackfoot,” the man told me as he inspected one of the carvings. He was joking, to a point.

Rock art is just that—interpretation. No direct descendant of the people who created this art across the American West can definitively explain it. The elders in tribes across the region certainly have an understanding, which they have passed down as stories through oral tradition.

Anthropologists and archaeologists study these places and have their own interpretations. For the casual visitor, the fun of seeing the ancient carvings is to come up with your own ideas for what they mean. If nothing else, these places inspire us.

A woman exploring the art along the trail to Mouse’s Tank at Valley of Fire saw a carving with a number of U-shaped “scallops” around its perimeter. To her, this represented a mountain. She thought the scalloped parts indicated the number of days the sun would take to travel over the mountain. That actually seemed plausible since we were in the rugged mountain areas of southeastern Nevada. But a Canadian tourist said he thought it represented early dentistry—the shape represented a jaw with teeth. Hmmm… now that you mention it…that also could be a possibility.

Hiking this short trail over deep sand is a feast for the senses. You will see hundreds of rock art images—some almost certainly depicting mountain sheep and deer. One man told me he saw a moose petroglyph. Snakes, turtles, trees, birds and other forms of life thrive here. Located just over an hour north of Las Vegas, Valley of Fire is an excellent place to view ancient rock art, and to experience a remote desert and mountain landscape. Be prepared, though. Take your own drinks and snacks as services are minimal.

Nine Mile Canyon

While archaeologists may attempt to interpret the rock art in Nine Mile Canyon, in central Utah, the Northern Utes have their own interpretations of the rock carvings, some of which were created by their own ancestors. Northern Ute Elder Clifford Duncan says that many rock art pictographs (paintings on rock) and petroglyphs (carvings on rock) are not decipherable because they are from the spirit world.

The road leading northeast into Nine Mile Canyon from Wellington, Utah, used to be accessible only by four-wheel-drive vehicles. It was a remote, rough, you’d-better-have-a-spare-tire-type of road surface. But the development of oil and gas in the area has opened access significantly. Now the road is partly paved, making it possible for passenger cars to travel the canyon, giving visitors a chance to view the rock art that seems to be on every flat rock surface in the long canyon. Despite its name, it’s far longer than nine miles, so expect a one-way drive of about 40 miles. The area is one of the richest sites in the country—with many individual rock illustrations (both petroglyphs and pictographs).

This rock art reflects the work of artists across centuries. Early images are crude geometric shapes indicative of the Fremont Culture. The more recent pieces, representing the historic period of the last couple hundred years, can be identified even by novices because they have horses with riders. They show weapons such as bows and arrows.

The most well-known petroglyph in Nine Mile Canyon is The Great Hunt, a spectacular image of hunters and their prey. It is deep in the canyon, a good hour-long drive from Wellington, and then a short walk from a new interpretive site.

In one area you can hike a short trail to the remnants of Fremont homes, gaining a view of their abodes and the canyon country itself.

Take your own supplies, including water and snacks or food, as you will find few services in the canyon. The only lodging close by is Nine Mile Canyon Ranch with a couple of rooms in the main house plus campsites and cabins.

Monument Valley

Filmmaker John Ford and actor John Wayne put Monument Valley on the map for most modern-day people, but this region with its spires, mittens, buttes, bluffs and other natural features has attracted visitors and been home to Navajo people for generations. For the Navajo Nation it is Tsé Bii’ Ndzisgaii—Valley of the Rocks.

The open expanses combined with the natural landforms make Monument Valley recognizable around the world. While Ford brought attention to this landscape, some moviegoers might recognize it from the long stretch of U.S. Highway 163 southwest of Mexican Hat, Utah, where Tom Hanks concluded his “run” in the 1994 film Forrest Gump. Even today, as you drive through the valley, you’ll see a sign commemorating the end of Gump’s run across America.

Learn more about the native people and their culture at the Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park. You can negotiate a self-driving tour of a portion of the park, but for access to a large region and better opportunity to hear the stories of the Navajo people, take one of their guided tours.

Harry Goulding attracted Hollywood to Monument Valley when he camped out on Ford’s doorstep. Goulding already operated a trading post in Monument Valley, and he wanted to see better opportunity for the Navajo residents, plus bring in more business for his own benefit, when he took photographs of the valley to Hollywood and showed them to Ford. The legendary director would follow Goulding to the valley, and return many times, making classic films such as 1939’s Stagecoach, 1949’s She Wore a Yellow Ribbon and 1956’s The Searchers with the equally legendary John Wayne.

Goulding’s Trading Post still serves the area and has lodging, a restaurant and more services. The Goulding Museum highlights the early film history connected to this region and has personal artifacts from the Goulding family and a cabin Wayne used.

First Mesa, Walpi

The Hopi people have inhabited First Mesa, the community of Walpi in northern Arizona, for centuries. In these days of modern intrusions, they have managed to remain somewhat isolated, and therefore maintain their traditions.

For my visit to Walpi, I have to rely on memory of its petroglyph art, for the tour leader who took me there would not allow cameras of any kind, nor even a notebook and pencil. This is not a site overly visited; as a result, you have the opportunity to spend time with the residents, who tell you of their lives, and, yes, will share a piece of flat bread, or sell you a piece of pottery hand-shaped and hand-fired over a fire built of sheep dung.

Four Corners

Possibly the best known ancient site in the West is Mesa Verde National Park in southwestern Colorado. Although other canyon dwelling sites are equally impressive, Four Corners country is a great place to begin the exploration. At Mesa Verde you can view and visit the ruins left behind by people who disappeared from this specific landscape about 700 years ago.

On top of Weatherill Mesa you will see evidence of their habitation including ancient irrigation systems. But when you descend into the cliffside lodging areas, you will see their cities. Among those you can visit are Balcony House, Cliff Palace, Long House and Spruce Tree House. Expect to hike, climb and descend ladders and steps, and sometimes even crawl on hands and knees as you take the tours of these dwellings.

As you maneuver the cliffside ladders, think about this: the people who once lived here hauled in water, food and everything else they needed for survival —by hand!

The Ancestral Puebloans lived on the mesa top for around 600 years until sometime during the late 1190s when they abandoned their mesa homes and built pueblos beneath the overhanging cliffs in the nearby canyons. These cliff structures ranged in size from one-room storage units to villages of more than 150 rooms. The people continued to farm on the mesa tops as they inhabited the cliff dwellings, repairing, remodeling and adding on for almost a century. The Ancestral Puebloans began abandoning these cliff homes in the late 1270s, establishing new homes in what are now Arizona and New Mexico, and by 1300 Mesa Verde was no long occupied.

In the new Mesa Verde Research and Visitor’s Center, located at the park entrance, you will learn more about the Ancestral Puebloans who once called this area home, and you will see exhibits highlighting the extensive collections held by the National Park Service.

The people who left Mesa Verde established new homes at places like Walpi on the Hopi Reservation in Arizona and Taos Pueblo in New Mexico.

You will find evidence of other canyon dwellers in places such as Canyon de Chelly in Arizona, which remains a home to members of the Navajo Nation who live and farm in its confines. At Canyon de Chelly National Monument, you can visit and view the canyon from above, on your own, by driving the park roads to various interpretive sites.

To gain a greater appreciation for the sheer rock walls and the canyon’s history and ecosystem, take a Navajo-guided tour. While some tours are conducted in large vehicles and jeeps, you can also see the canyon from horseback. A Navajo guide will lead you deep into the area, telling stories as you ride. Horses will splash across the Chinle Wash, sometimes sinking into the quicksand bottom. But you will gain a glimpse into ancient rock art and, more important, hear the stories of the people who have deep ties to this landscape.

Taos Pueblo

Once upon a time, folks believed the people who inhabited places like Mesa Verde disappeared. But of course the reality is that these cultures moved and evolved. The people once called Anasazi, are now referred to as Ancestral Puebloans. Their modern descendants are the Pueblo people of New Mexico, plus members of the Hopi and Navajo tribes.

Taos Pueblo, near Taos, New Mexico, remains a vibrant home and village where generations share the complex pueblo. It is the largest standing multi-storied pueblo in the United States and has endured for nearly 10 centuries. The people rely on crystal clear waters from the Rio Pueblo, which originate high in the mountains at Blue Lake, a body of water sacred to the people of the pueblo.

Historically Taos Pueblo was a major center of trade between the Pueblo people of the Rio Grande Valley and Plains Indians. The Puebloans exchanged items such as turquoise and corn for buffalo hides brought south by the Plains traders. Each season trade fairs took place. They gave way to merchant caravans that traveled along the Chihuahua Trail between the cities of Mexico and northern New Mexico. The Pueblo Indians living here took part in the Great Pueblo Revolt of 1680, driving the Spanish out of New Mexico for a dozen years. They were engaged in yet another dispute, the Taos Revolt, in 1847, that led to the deaths of many Puebloan people and territorial leaders.

Through it all the people maintained their cultural traditions, some of which they share with modern visitors. These include crafts such as jewelry making. They hold a Feast Day each fall, which is open to the public, and have other periodic cultural events for public visitors.

Cellphones generally don’t work, or should not be used in these traditional homesites and canyon locations, and that is as it should be. When you take the time to seek out these ancient places, set aside those modern connections and allow yourself the opportunity to enjoy the experience of being in a place where early people took the time to create art and leave behind evidence of their presence.

While researching this article, Candy Moulton visited Northern Ute Elder Clifford Duncan. After she toured the rock art in Nine Mile Canyon, Duncan gave her his personal flute. Someday, perhaps, she will be given the gift of how to play it.

{

Photo Gallery

– All images by Candy Moulton –