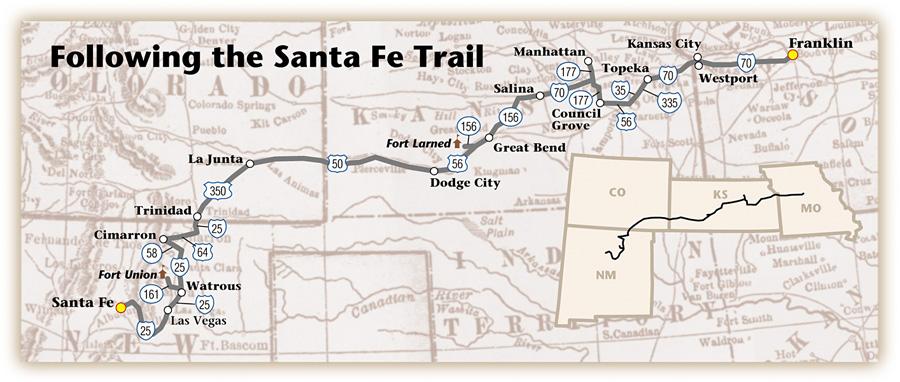

When first opened to traffic in 1821, the Santa Fe Trail linked the American markets along the Missouri River with the long-established Mexican trade center of Santa Fe, New Mexico.

When first opened to traffic in 1821, the Santa Fe Trail linked the American markets along the Missouri River with the long-established Mexican trade center of Santa Fe, New Mexico.

The culturally diverse points supported a commercial road that not only connected those two nations, but also crossed the sovereign lands of the Kansa, Osage and other tribes.

The ethnic and landscape diversity of the early 19th century remains pronounced in the early 21st century. In Santa Fe the soft sounds of Spanish and Indian languages, and the sights of men and women trading jewelry in front of the Palace of the Governors are reminders of the long-standing customs and culture of this four-centuries-old Southwestern city. The hustle-bustle of the Kansas City metropolitan area in Missouri has seemingly swallowed up the historic locations where the Santa Fe Trail originated, but deep down you can find remnants and reminders of it.

The Trail Genesis

Although American Indians undoubtedly used segments of the route for generations, likely the first white man to follow the Santa Fe pathway was Frenchman Pierre Vial, who traveled from St. Louis to Santa Fe in 1792. In 1806, American Capt. Zebulon Pike ventured up the Arkansas River on a portion of the route.

The trail genesis occurred when Mexico won its independence from Spain in 1821, setting up the possibility of trade relations with the United States. William Becknell pioneered the commercial road to Santa Fe. Even before actual word of the Mexican independence reached St. Louis, he had organized a trading company and advertised in Franklin’s Missouri Intelligencer for men. In his ad Becknell stated: “Every man will fit himself for the trip, with a horse, a good rifle, and as much ammunition as the company may think necessary for a tour or 3 months trip, & sufficient cloathing [sic] to keep him warm and comfortable. Every man will furnish his equal part of the fitting out of our trade and receive an equal part of the product.”

Becknell and three or four companions left Arrow Rock on September 1, 1821, traveling west with their pack animals on what became the Mountain Branch of the Santa Fe Trail and arriving in Santa Fe in November 1821. There they traded American goods for money, which they brought back to Missouri. As observer Robert Duffus later recalled: “My father saw them unload when they returned, and when their rawhide packages of silver dollars were dumped on the sidewalk one of the men cut the thongs and the money spilled out and clinking on the stone pavement rolled into the gutter. Everyone was excited and the next spring another expedition was sent out.”

That same year, not long after Becknell arrived in Santa Fe, trappers Jacob Fowler and Hugh Glenn, and traders Thomas James and John McKnight also entered the settlement. In the spring of 1822 Col. Benjamin Cooper and his 15 men left Missouri before Becknell could make his second venture. The race was on to capture the lucrative Santa Fe trade goods that included silver, furs and mules.

Movin’ in Missouri

Though the recognized eastern terminus of the Santa Fe Trail is in Franklin, Missouri, I start my trip in the Kansas City area with a visit to the Arabia Steamboat Museum. The goods that sunk to the bottom of the Missouri River when the Arabia went down in 1856 are admittedly of later vintage than those first carried over the Santa Fe Trail. Nevertheless the museum provides a good sense of trade items available during the 19th century.

The trade goods that did travel over the trail can be credited to a Missouri senator who sponsored legislation in 1824-25 that authorized a survey to establish the route. The survey goal, Sen. Thomas Hart Benton wrote, “Is thoroughness for it is not a County or State road which they have to mark out but a highway between Nations.”

The senator’s great-nephew, also named Thomas Hart Benton, became a well-known painter and sculptor. In Kansas City, visit that Benton’s home, which features a carriage house he converted into an art studio.

While in Kansas City, you should also make stops at the Alexander Majors House, the Harris-Kearney House, which now houses the Westport Historical Society, and the Seth Ward Home.

Crossing Kansas

From the Kansas City metro area, continue west to Council Grove, the heart of the beautiful Flint Hills of Kansas.

At the Council Oak in 1825 the Osage negotiated a treaty granting a right-of-way and safe passage to travelers on the Santa Fe Trail. The Kansa granted similar concessions in the Dry Turkey Creek Treaty of August 16, 1825. That treaty called for payment of $300 to the tribe and stipulated that the Indians would “render such friendly aid and assistance as may be in their power, to any of the citizens of the United States, or of the Mexican Republic, as they may at any time happen to meet or fall in with on the road….”

Learn more about these tribes and their connections to Council Grove at the Kaw Mission in town. At the mission you can get directions to Allegawaho Heritage Memorial Park, which preserves the walls of Kaw houses built for tribespeople under provisions in the treaties. I recommend walking or biking along the two-mile heritage trail so you can see remnants of huts used by Kaw tribal members before they were removed to Oklahoma in 1873.

June is a good month to visit the Kaw Mission as the Kaws host their inter-tribal powwow during Washunga Days; every other fall, the Kaws present “Voices of the Wind People.” That pageant will be held this year in September. The performance takes place near the Santa Fe Trail crossing on the Neosho River. The story is told from the perspectives of Kansa Chief Allegawaho and trader Seth Hays who came to Council Grove in the mid-1800s. He squatted on land that was part of the Kansa reserve and opened a trading store.

To further explore the Flint Hills, head south of Council Grove to the Tallgrass Prairie National Monument, then head north on the Flint Hills Scenic Byway for a visit to the Flint Hills Discovery Center in Manhattan. The center opened this past April, and it features extensive exhibits sharing the customs and culture of this prairie region.

From Manhattan, head to Great Bend to see the well-preserved Fort Larned, established in 1859 to protect Santa Fe traffic from Indian raids. The Larned area offers many Santa Fe Trail sites associated with two routes: the Wet Route, for its proximity to the Arkansas River (roughly following today’s U.S. 56), and the Dry Route, located farther north and west of the river. These routes converge at Fort Dodge, originally built in 1865 to the east of present-day Dodge City (the rebuilt fort was later converted to the Kansas Soldiers Home). More than 100 limestone markers mark the route and important trail sites in this area of western Kansas.

Trail Street in Dodge City overlays the Santa Fe Trail, and it’s always fun to explore this old cowtown. Santa Fe Trail enthusiasts got a gift from the city last September when the Santa Fe Trail Association unveiled the updated and new signs at the trail ruts. That gift is one of the reasons why this magazine named Dodge City a “Top 10 True Western Town” this year. These signs direct visitors to the Mountain and Cimarron Branches, as well as point out other Dodge City trail sites.

I’m going to follow the advice of the Mountain Branch sign and head across the shortgrass prairie of western Kansas and eastern Colorado to Bent’s Fort, just east of La Junta, Colorado.

Tourin’ the Mountain Branch

During the six years Ceran St. Vrain worked for Bernard Pratte in St. Louis, he heard stories of the fur trade out West and became enamored with the thought of heading to the frontier. In 1824, he hired on with Becknell’s trading caravan en route to Santa Fe. A few years later, during the winter of 1829-30, William Bent took part in a trapping expedition on the upper Arkansas River where he befriended the Cheyennes.

St. Vrain became acquainted with Charles and William Bent, and the three young men formed the Bent, St. Vrain Company in 1831. It quickly became a commercial trade enterprise covering thousands of square miles in present-day Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Texas, Utah and Wyoming. The company owned a trading house in Taos, New Mexico, and William Bent oversaw construction of the company’s adobe fort on the Arkansas River in 1832. First known as Fort William, the site later became Bent’s Fort (and is often referred to as Bent’s Old Fort).

After your tour of Bent’s Old Fort, I recommend you head to Trinidad via U.S. 350. This route generally parallels the Santa Fe Trail and crosses the western portion of the Comanche National Grasslands. Near Timpas, you can see clearly visible Santa Fe Trail segments. In this area, in September 1837, Pawnees attacked a trade caravan led by Ceran’s younger brother, Marcellin. The Indians killed one member of the trade caravan, wounded three others and stole three horses and nine mules carrying some $3,273.13 in trade goods.

I like Trinidad. The streets are crooked, wiggling through the downtown area where they overlay the Mountain Branch of the Santa Fe Trail. Oxen or mules tend to walk in zigzag directions as they pull their heavy wagons. That makes the trail they leave—or in this case the Trinidad streets—a bit crooked. The intersection at Commercial and Main Streets is where two segments of the Santa Fe Trail converged.

One of the first settlers in the Trinidad area was Gabriel Gutierrez. He arrived in 1859 to seek range for his sheep. After him, came Felipe Baca and Pedro Valdez. The Baca House, built in 1870, is just one of the many historic buildings in Trinidad. It is part of History Colorado’s Trinidad History Museum, which includes the Santa Fe Trail Museum, the Bloom Mansion and a wonderful heritage garden area. The property also houses the Santa Fe Trail Scenic and Historic Byway Visitor Center, and it is within walking distance of downtown and other historical properties in the area. I recommend you pick up a copy of the guide, “A Walk Through the History of Trinidad,” and enjoy the sites.

Ever since Becknell first traveled the trail with his pack horses, pioneers began making gradual improvements over the Mountain Branch, but getting their wagons over the steep and rugged Raton Pass south of Trinidad presented a significant challenge. Then in 1866 trapper Richens Lacy Wootton—better known as Uncle Dick—built a toll road over the pass. You will find it is much easier to cross Raton Pass on I-25.

Once you reach New Mexico, continue to follow the Mountain Branch to Cimarron. You’ll see trail ruts in places north of U.S. 160. Keep your eyes peeled for the buffalo that still roam this land.

From Cimarron, I recommend you take a detour north of Watrous to the site of Fort Union, where you’ll find Santa Fe Trail segments leading to and from the 1851 fort location. The ruins of the fort are particularly appealing to see late in the afternoon with the New Mexico sun burnishing the ruts.

After your tour, head back on I-25 for the final leg of the journey, which ends with the trail in Santa Fe.

Santa Fe’s appeal is unique for its outstanding shopping, history and culture. A visit to the Palace of Governors is a must where, if you still have jingle in your jeans, you can buy some authentic New Mexico products. Around the corner, you should visit the New Mexico History Museum.

My Santa Fe friend Johnny D. Boggs assures me the best burger in the area can be found at the Bobcat Bite. I actually ate at Harry’s Roadhouse, which had a dandy burger. While I was remarking on how good it was, the young man waiting on me even recommended Bobcat Bite!

Road Warrior Candy Moulton recommends joining the Santa Fe Trail Association (SantaFeTrail.org) and picking up a copy of her book Roadside History of Colorado, as well as a copy of Following the Santa Fe Trail by Marc Simmons and Hal Jackson.

hen first opened to traffic in 1821, the Santa Fe Trail linked the American markets along the Missouri River with the long-established Mexican trade center of Santa Fe, New Mexico. The culturally diverse points supported a commercial road that not only connected those two nations, but also crossed the sovereign lands of the Kansa, Osage and other tribes.

The ethnic and landscape diversity of the early 19th century remains pronounced in the early 21st century. In Santa Fe the soft sounds of Spanish and Indian languages, and the sights of men and women trading jewelry in front of the Palace of the Governors are reminders of the long-standing customs and culture of this four-centuries-old Southwestern city. The hustle-bustle of the Kansas City metropolitan area in Missouri has seemingly swallowed up the historic locations where the Santa Fe Trail originated, but deep down you can find remnants and reminders of it.

The Trail Genesis

Although American Indians undoubtedly used segments of the route for generations, likely the first white man to follow the Santa Fe pathway was Frenchman Pierre Vial, who traveled from St. Louis to Santa Fe in 1792. In 1806, American Capt. Zebulon Pike ventured up the Arkansas River on a portion of the route.

The trail genesis occurred when Mexico won its independence from Spain in 1821, setting up the possibility of trade relations with the United States. William Becknell pioneered the commercial road to Santa Fe. Even before actual word of the Mexican independence reached St. Louis, he had organized a trading company and advertised in Franklin’s Missouri Intelligencer for men. In his ad Becknell stated: “Every man will fit himself for the trip, with a horse, a good rifle, and as much ammunition as the company may think necessary for a tour or 3 months trip, & sufficient cloathing [sic] to keep him warm and comfortable. Every man will furnish his equal part of the fitting out of our trade and receive an equal part of the product.”

Becknell and three or four companions left Arrow Rock on September 1, 1821, traveling west with their pack animals on what became the Mountain Branch of the Santa Fe Trail and arriving in Santa Fe in November 1821. There they traded American goods for money, which they brought back to Missouri. As observer Robert Duffus later recalled: “My father saw them unload when they returned, and when their rawhide packages of silver dollars were dumped on the sidewalk one of the men cut the thongs and the money spilled out and clinking on the stone pavement rolled into the gutter. Everyone was excited and the next spring another expedition was sent out.”

That same year, not long after Becknell arrived in Santa Fe, trappers Jacob Fowler and Hugh Glenn, and traders Thomas James and John McKnight also entered the settlement. In the spring of 1822 Col. Benjamin Cooper and his 15 men left Missouri before Becknell could make his second venture. The race was on to capture the lucrative Santa Fe trade goods that included silver, furs and mules.

Movin’ in Missouri

Though the recognized eastern terminus of the Santa Fe Trail is in Franklin, Missouri, I start my trip in the Kansas City area with a visit to the Arabia Steamboat Museum. The goods that sunk to the bottom of the Missouri River when the Arabia went down in 1856 are admittedly of later vintage than those first carried over the Santa Fe Trail. Nevertheless the museum provides a good sense of trade items available during the 19th century.

The trade goods that did travel over the trail can be credited to a Missouri senator who sponsored legislation in 1824-25 that authorized a survey to establish the route. The survey goal, Sen. Thomas Hart Benton wrote, “Is thoroughness for it is not a County or State road which they have to mark out but a highway between Nations.”

The senator’s great-nephew, also named Thomas Hart Benton, became a well-known painter and sculptor. In Kansas City, visit that Benton’s home, which features a carriage house he converted into an art studio.

While in Kansas City, you should also make stops at the Alexander Majors House, the Harris-Kearney House, which now houses the Westport Historical Society, and the Seth Ward Home.

Crossing Kansas

From the Kansas City metro area, continue west to Council Grove, the heart of the beautiful Flint Hills of Kansas.

At the Council Oak in 1825 the Osage negotiated a treaty granting a right-of-way and safe passage to travelers on the Santa Fe Trail. The Kansa granted similar concessions in the Dry Turkey Creek Treaty of August 16, 1825. That treaty called for payment of $300 to the tribe and stipulated that the Indians would “render such friendly aid and assistance as may be in their power, to any of the citizens of the United States, or of the Mexican Republic, as they may at any time happen to meet or fall in with on the road….”

Learn more about these tribes and their connections to Council Grove at the Kaw Mission in town. At the mission you can get directions to Allegawaho Heritage Memorial Park, which preserves the walls of Kaw houses built for tribespeople under provisions in the treaties. I recommend walking or biking along the two-mile heritage trail so you can see remnants of huts used by Kaw tribal members before they were removed to Oklahoma in 1873.

June is a good month to visit the Kaw Mission as the Kaws host their inter-tribal powwow during Washunga Days; every other fall, the Kaws present “Voices of the Wind People.” That pageant will be held this year in September. The performance takes place near the Santa Fe Trail crossing on the Neosho River. The story is told from the perspectives of Kansa Chief Allegawaho and trader Seth Hays who came to Council Grove in the mid-1800s. He squatted on land that was part of the Kansa reserve and opened a trading store.

To further explore the Flint Hills, head south of Council Grove to the Tallgrass Prairie National Monument, then head north on the Flint Hills Scenic Byway for a visit to the Flint Hills Discovery Center in Manhattan. The center opened this past April, and it features extensive exhibits sharing the customs and culture of this prairie region.

From Manhattan, head to Great Bend to see the well-preserved Fort Larned, established in 1859 to protect Santa Fe traffic from Indian raids. The Larned area offers many Santa Fe Trail sites associated with two routes: the Wet Route, for its proximity to the Arkansas River (roughly following today’s U.S. 56), and the Dry Route, located farther north and west of the river. These routes converge at Fort Dodge, originally built in 1865 to the east of present-day Dodge City (the rebuilt fort was later converted to the Kansas Soldiers Home). More than 100 limestone markers mark the route and important trail sites in this area of western Kansas.

Trail Street in Dodge City overlays the Santa Fe Trail, and it’s always fun to explore this old cowtown. Santa Fe Trail enthusiasts got a gift from the city last September when the Santa Fe Trail Association unveiled the updated and new signs at the trail ruts. That gift is one of the reasons why this magazine named Dodge City a “Top 10 True Western Town” this year. These signs direct visitors to the Mountain and Cimarron Branches, as well as point out other Dodge City trail sites.

I’m going to follow the advice of the Mountain Branch sign and head across the shortgrass prairie of western Kansas and eastern Colorado to Bent’s Fort, just east of La Junta, Colorado.

Tourin’ the Mountain Branch

During the six years Ceran St. Vrain worked for Bernard Pratte in St. Louis, he heard stories of the fur trade out West and became enamored with the thought of heading to the frontier. In 1824, he hired on with Becknell’s trading caravan en route to Santa Fe. A few years later, during the winter of 1829-30, William Bent took part in a trapping expedition on the upper Arkansas River where he befriended the Cheyennes.

St. Vrain became acquainted with Charles and William Bent, and the three young men formed the Bent, St. Vrain Company in 1831. It quickly became a commercial trade enterprise covering thousands of square miles in present-day Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Texas, Utah and Wyoming. The company owned a trading house in Taos, New Mexico, and William Bent oversaw construction of the company’s adobe fort on the Arkansas River in 1832. First known as Fort William, the site later became Bent’s Fort (and is often referred to as Bent’s Old Fort).

After your tour of Bent’s Old Fort, I recommend you head to Trinidad via U.S. 350. This route generally parallels the Santa Fe Trail and crosses the western portion of the Comanche National Grasslands. Near Timpas, you can see clearly visible Santa Fe Trail segments. In this area, in September 1837, Pawnees attacked a trade caravan led by Ceran’s younger brother, Marcellin. The Indians killed one member of the trade caravan, wounded three others and stole three horses and nine mules carrying some $3,273.13 in trade goods.

I like Trinidad. The streets are crooked, wiggling through the downtown area where they overlay the Mountain Branch of the Santa Fe Trail. Oxen or mules tend to walk in zigzag directions as they pull their heavy wagons. That makes the trail they leave—or in this case the Trinidad streets—a bit crooked. The intersection at Commercial and Main Streets is where two segments of the Santa Fe Trail converged.

One of the first settlers in the Trinidad area was Gabriel Gutierrez. He arrived in 1859 to seek range for his sheep. After him, came Felipe Baca and Pedro Valdez. The Baca House, built in 1870, is just one of the many historic buildings in Trinidad. It is part of History Colorado’s Trinidad History Museum, which includes the Santa Fe Trail Museum, the Bloom Mansion and a wonderful heritage garden area. The property also houses the Santa Fe Trail Scenic and Historic Byway Visitor Center, and it is within walking distance of downtown and other historical properties in the area. I recommend you pick up a copy of the guide, “A Walk Through the History of Trinidad,” and enjoy the sites.

Ever since Becknell first traveled the trail with his pack horses, pioneers began making gradual improvements over the Mountain Branch, but getting their wagons over the steep and rugged Raton Pass south of Trinidad presented a significant challenge. Then in 1866 trapper Richens Lacy Wootton—better known as Uncle Dick—built a toll road over the pass. You will find it is much easier to cross Raton Pass on I-25.

Once you reach New Mexico, continue to follow the Mountain Branch to Cimarron. You’ll see trail ruts in places north of U.S. 160. Keep your eyes peeled for the buffalo that still roam this land.

From Cimarron, I recommend you take a detour north of Watrous to the site of Fort Union, where you’ll find Santa Fe Trail segments leading to and from the 1851 fort location. The ruins of the fort are particularly appealing to see late in the afternoon with the New Mexico sun burnishing the ruts.

After your tour, head back on I-25 for the final leg of the journey, which ends with the trail in Santa Fe.

Santa Fe’s appeal is unique for its outstanding shopping, history and culture. A visit to the Palace of Governors is a must where, if you still have jingle in your jeans, you can buy some authentic New Mexico products. Around the corner, you should visit the New Mexico History Museum.

My Santa Fe friend Johnny D. Boggs assures me the best burger in the area can be found at the Bobcat Bite. I actually ate at Harry’s Roadhouse, which had a dandy burger. While I was remarking on how good it was, the young man waiting on me even recommended Bobcat Bite!

Road Warrior Candy Moulton recommends joining the Santa Fe Trail Association (SantaFeTrail.org) and picking up a copy of her book Roadside History of Colorado, as well as a copy of Following the Santa Fe Trail by Marc Simmons and Hal Jackson.

Photo Gallery

– All photos by Candy Moulton; Historical photo: True West Archives –