The old Bob Seger song claimed that Rock ‘n’ Roll never forgets.

The old Bob Seger song claimed that Rock ‘n’ Roll never forgets.

History does, all too often.

Take the case of Clement Rolla Glass, who died too young and too early to parlay his connection to Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

Going by the name Rolla, he was born into a prominent California ranch family in 1867 and graduated with an engineering degree from the College of the Pacific in 1890. He worked for the railroads before gold fever struck him after the 1896 discovery in Alaska.

Rolla eventually headed to Bolivia to supervise the Concordia mine for the Andes Tin Company. (He knew Bolivia, having traveled there after high school and married a local girl in 1885.) While at the central Andes mine, about 70 miles southeast of La Paz, Rolla had his brush with Wild West history.

In 1906, Rolla hired an American, Santiago Maxwell, to purchase livestock that would haul supplies to and from the mine. He paid him $150 a month, plus room and board.

Maxwell, actually an alias for outlaw Butch Cassidy, quickly proved his worth. On his first job, with $200 to buy mules, Butch returned with a fine set of animals—and $50 change. An impressed Rolla soon had the new guy carry Concordia’s payroll remittances, which sometimes exceeded $100,000. Butch accounted for all the money.

Shortly after that, Enrique Brown drifted in. Butch knew him, so Rolla hired him on as well. Brown, of course, was the Sundance Kid.

At some point, Rolla discovered the real identities of his employees. (Wild Bunch expert Dan Buck suspects an engineer saw wanted posters for the duo in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and told Rolla.) Butch and Sundance, though, must have assured the boss they had no intention of robbing his company, because he kept them on.

When Rolla’s assistant, Percy Seibert, returned to Bolivia at the end of 1906, Rolla revealed to him the true identities of Butch and Sundance. When Rolla returned to the headquarters in La Paz, he left Seibert as acting superintendent of the mine. Seibert claimed that during this time, he became close with the outlaws, who told of their criminal exploits in the States.

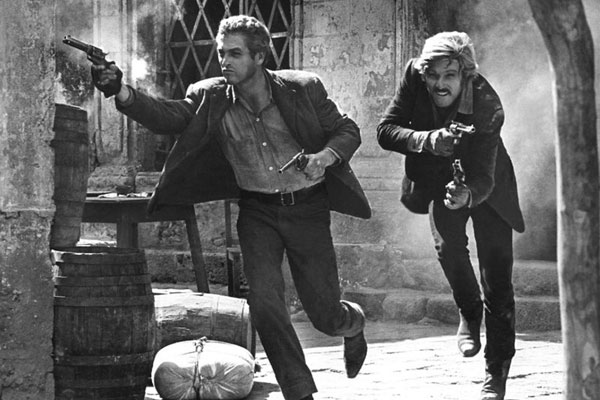

Around May 1908, Butch and Sundance quit and moved on. Maybe the heat was on; maybe they were just restless. They didn’t have much time left, as it turned out. On November 7, three days after they pulled their last job, they died after a shoot-out with the local constabulary in San Vicente. A wounded Butch killed Sundance before putting a bullet in his own head, according to the historical record.

Ironically, Rolla would take the same trail soon after.

He was in poor health, as letters from his family in the States revealed. He died on January 2, 1909, in a Buenos Aires hotel. Family tradition says he accidentally shot himself while cleaning his guns. The police report states Rolla committed suicide, first shooting himself in the stomach and then the head.

Rolla died without telling his story—especially the chapter on Butch and Sundance. That was left up to Seibert, who shared his memories with author James D. Horan in the 1950s.

Yet at least some of what Seibert recalled was bogus, Buck says. Other parts can’t be proven. Either way, Seibert had a central role in those tales.

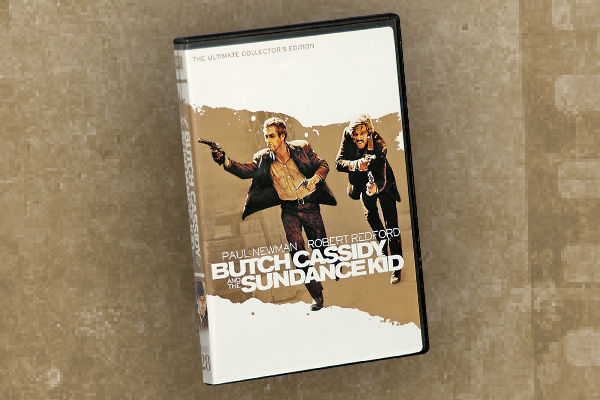

To make matters worse for Rolla, the 1969 Western Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid didn’t even mention him. Instead, Seibert (called Percy Garris by the filmmakers) hired the boys.

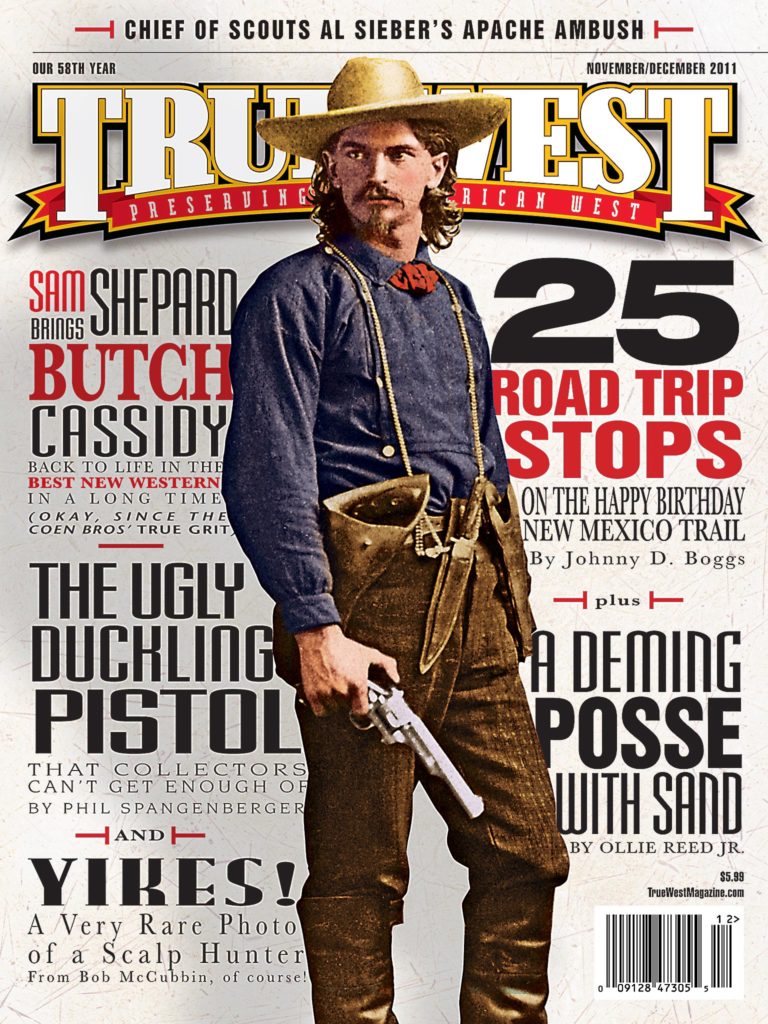

In recent years, some Rolla kin have been trying to boost his profile, to make sure he gets credit for employing Butch and Sundance. But it’s an uphill battle, going against more than 100 years of false information.

As Bob Seger sings, they’re runnin’ against the wind.