We’ve seen them ride off into the sunset at the end of the story, but what happens when the heroes and outlaws, the men of myth and grand adventure, come back late in life to climb back up on the horse for one last ride?

We’ve seen them ride off into the sunset at the end of the story, but what happens when the heroes and outlaws, the men of myth and grand adventure, come back late in life to climb back up on the horse for one last ride?

Movie fans might remember when Sean Connery played an aged Robin Hood, back from the Crusades for a final fight to the death with the Sheriff of Nottingham, in the movie Robin and Marion. James Arness made an entire career of bringing back an ever-older Matt Dillon in one Gunsmoke TV movie after another. Hugh O’Brian’s Wyatt Earp came back, just twice, but Earp the character came back as a much older man, played by James Garner, in the movie Sunset. He’s about to come back again, this time to go up against Al Capone in the early 1920s. Harrison Ford will play the part in Black Hats.

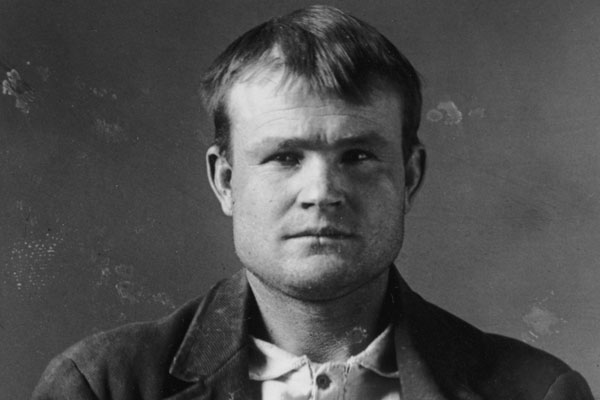

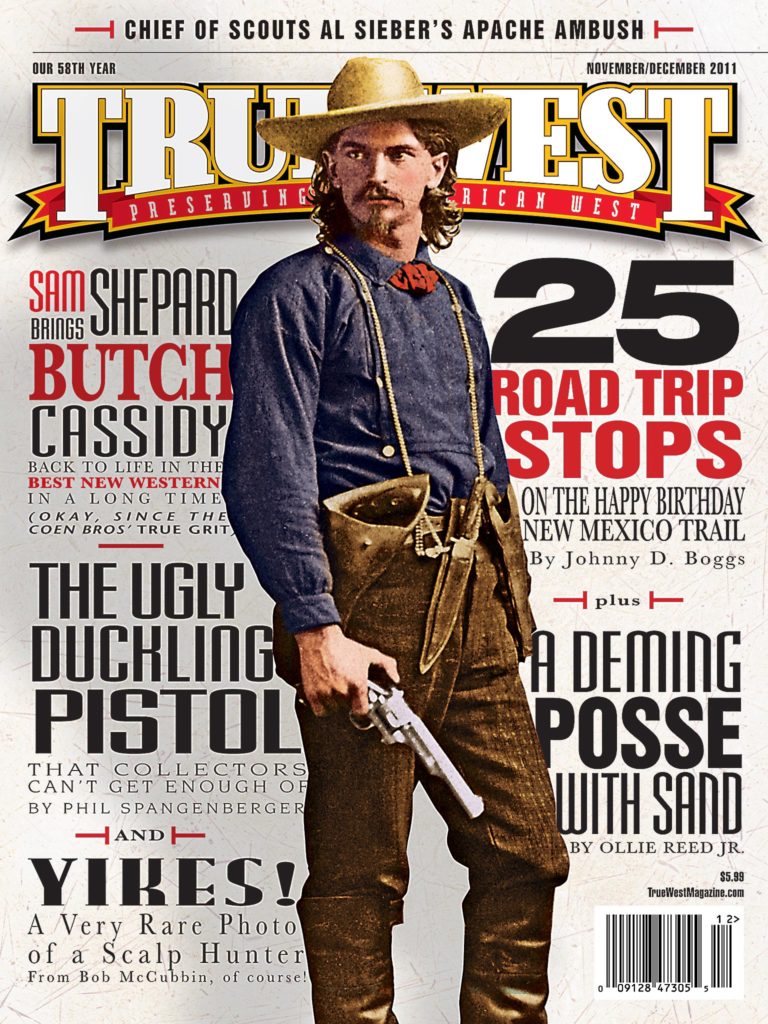

So the idea of Butch Cassidy, alive and living in South America, is a natural, and Mateo Gil’s film, Blackthorn, strikes all the right notes. The movie hit the big screen in October, and it will be playing in Oklahoma City, at the Oklahoma City Museum of Art, on December 1, 2011.

Spanish director Gil and his friend, scriptwriter Miguel Barros, have created a perfect, truly poetic fantasy of Robert Leroy Parker, living high in Bolivia in 1927 as a retired gentleman raising and selling horses. No one, least of all the locals who work his ranch, suspects they’re in the presence of the former outlaw partner of the late Sundance Kid (a.k.a. Harry Longabaugh).

But Cassidy, who’s taken the name James Blackthorn, is feeling a need to return to the States to see the grown child of Etta Place. Cassidy has been writing the boy, Ryan, for some time; we find out that Ryan may be either his son or the Kid’s. He arranges a deal with some American businessmen (who he clearly dislikes) to sell his stock and return to America.

This Cassidy soon finds himself in the same world as the Cassidy from 1969’s Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid; if ever there was a better target for the casual whims of misfortune, he hasn’t yet been invented. En route to America, Cassidy, money stashed in his saddlebags, is attacked in the “middle of nowhere” by engineer Eduardo Apodaca (Eduardo Noriega), who tries to steal Cassidy’s horse. When Cassidy’s horse spooks and takes off with the money, Apodaca tells Cassidy he’s on the run from the hired thugs of tin magnate Simón Patiño, historically one of the richest men in the world at the time. Apodaca offers to pay back Cassidy with the payroll money he stole from the mining operation, if Cassidy helps him retrieve it.

This plan sets up a perfect storm for Cassidy, who has two significant aspects to his profile: he forms friendships with outlaws, and he is doomed to be pursued by faceless men on horseback. In Blackthorn, we never hear Cassidy ask, “Who are those guys?” All he needs to be told is that they’re the minions of the South American equivalent of a railroad tycoon, and he’s back in action.

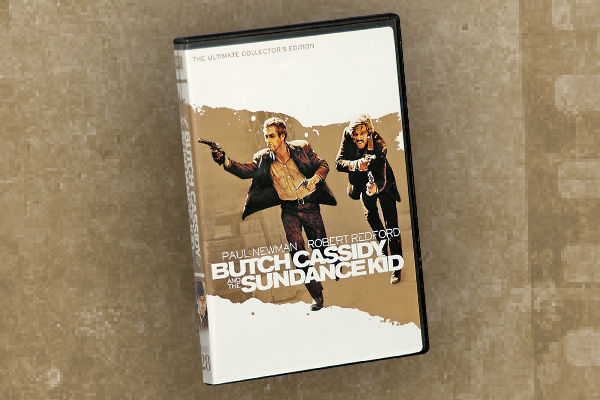

Most Westerns fans know the outlaw duo from the George Roy Hill-directed 1969 film, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. The brilliance of William Goldman’s script and the charm of actors Paul Newman and Robert Redford, respectively, made the movie a huge hit and planted the two characters in the public’s mind as if they had been around forever. TV series, like Alias Smith and Jones, tried to appropriate that spirit, and other movies have told the story of Butch and Sundance in their earlier years, but that single film put the pair nearly on a par with better established Western figures like Billy the Kid and Wyatt Earp.

Gil respects the earlier film, and he works from our idea of Cassidy. Flashbacks show us Cassidy, Sundance and a more dynamic Etta Place during their glory years, but they add texture to the story and understanding to Cassidy’s present emotions. Blackthorn is not a sequel to Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, nor is it a revision in any sense, but it does draw on the audience’s memory and affection for the character without cheapening him.

Gil has also added a new character, Mackinley (played by Stephen Rea), who was one of Cassidy’s original pursuers, the Gerard to his Kimble, but who has settled into an innocuous and reasonably comfortable life in a Bolivian village. Even though he comes upon an unconscious and vulnerable Cassidy, Mackinley admits his hunger for the chase has been extinguished. “The fatigue, the years of pursuit, carrying out one’s duty is, believe me, exhausting,” he tells the injured Cassidy. “We’re too old to keep on playing.”

“It never was a game to me,”

Cassidy replies.

Gil spoke to us from his home in Madrid. He apologized for his English, yet I found him funny and enthusiastic, and eloquent.

Henry Cabot Beck: How did you get to know Westerns?

Mateo Gil: When I was a child, in the public television, there were only two channels. One of them, every Saturday afternoon, they put a movie, and it was usually a Western, or maybe a movie from Rome, but mainly Westerns. So my first consciousness about cinema was through Westerns.

Were they European or American Westerns?

No—mainly they were classical American Westerns. I think I saw every Western. Every John Ford movie was in this television program, [as were the movies of] Howard Hawks. Then when I grew up, I started watching more modern Westerns, like Peckinpah. All these ’70s directors—[Sydney] Pollack, Arthur Penn. I’ve seen a lot of Westerns.

We were watching Italian Westerns, dubbed in English, while you were watching American Westerns, dubbed in Spanish.

[Laughs.] Yeah. But when you grow up and you see this movie with subtitles, you think, “Oh my God! This is his voice.” When you hear Clint Eastwood for the first time with his real voice, in English, you think his voice is really weird.

How close is your movie to the 1969 film?

I think Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, the movie by George Roy Hill, is so good, that from this moment on, every director was worried or scared about making a new movie about this character. But the character is so interesting; I think there are more movies to be made about Butch Cassidy….

I think my movie is a kind of intimate Western. I was inspired in the beginning by filmmakers like Peckinpah, and at the end, I was more inspired by classical Westerns, like John Ford’s. During the time I was preparing the movie, I was thinking, this movie is carrying me to John Ford. I’m not deciding, the movie is making the choices. In the beginning I wanted a more ‘70s style, but by the end, the movie is more of a mixture of the ‘70s and the classical Western—the ‘50s or early ‘60s Western.

The name Blackthorn sounds like a knight, out of Arthur. Where did the name come from?

When Miguel [Barros] was just writing the script, I was to his house, reading the lines and everything, and talking about my opinion, as a friend. I wasn’t going to direct it.

One night we went out to a bar, and we were talking about the title, because he didn’t have a good title, and he was very worried about that. At that time I was looking—you know, these things where you serve the beer?

The tap handle?

Yeah. Okay. There is a kind of Scottish cider called Blackthorn. [Laughs.] I told my friend, “Why don’t you name the character Blackthorn?” And that’s the title!…

The title of the first song in the movie, that Sam Shepard sings, that was a very much better title “Ain’t No Grave.” The line is like, “Ain’t no grave, can hold my body down.” But it was too late to change it. (Laughs.)

Did you know some members of the actual Wild Bunch became actors in early Westerns?

Let me tell you—do you know that in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, in Roy Hill’s movie, in the original script, there was a scene that is not in the movie, where Paul Newman and Robert Redford went into a cinema. In this cinema, there was a movie, and this movie was the movie you see now, in the beginning of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, if you remember, during the credits, black and white images, like a silent movie. They saw this movie, and they realized that the movie was about them. And in that movie, they died! So they went out of the theater saying, “Oh, f—ing movie!” You know?

In Blackthorn, we had a similar idea, a kind of homage. We shot a final scene that’s not in the movie, where you saw Butch Cassidy two years later, in Los Angeles. You saw he was older now, kind of tired and kind of sad, and he was riding a horse, but stopped, just sitting.

You hear a voice saying, “Hey You! Man with the black hat! You! Look at me.” Then you realize that Cassidy, two years later, was an extra in a Hollywood movie, about bandits.

Then you hear the director say to Sam Shepard: “Please smile a little—this is the final scene of the movie.”

So Sam smiles, like a man out of place. The director says, “Okay! Action! Go!” and all the riders ride off.

In the editing room, we felt it didn’t work with the tone of the film. Too jokey. So I think it will be with the extras, in the DVD.

Did you deliberately make it unclear whether Butch or Sundance is the father of Etta’s son?

[Laughs.] The idea is that he is Sundance’s son, but the idea was, at the same time, to suggest that the three of them had relationships, that Butch and Etta had a relationship too. So the ambiguity at the end is kind of a secondary effect. But we liked it.

For me, the important moment about this son is when Butch says to Sundance (in flashback), “Why do you think he’s your son?”

Sundance’s answer is, “He would still be my son.”

Sundance doesn’t really mind if it’s his, or Butch Cassidy’s son, because they are brothers. This is the important idea.

Why does Cassidy take time to identify himself in the letters he writes to his nephew/son?

We talked, the writer and me, we talk a lot about this—I don’t know if I should say problem—but we were very aware about how explicit we should have been about Butch Cassidy’s name. Actually we thought a lot of times, when writing the script, about the idea of not mentioning Butch Cassidy at all. We had this idea that you could see the movie, and at the end, say, “Maybe he is not Butch Cassidy.”

So we tried in the script to take off the name. The main problem was the conversation with Mackinley, because Mackinley is asserting he is Butch Cassidy.

But even though we thought very deeply about making this ambiguous, his real identity, because we wanted to say something like, it doesn’t matter if he is Butch Cassidy or not. The important thing is how he thinks, how he acts. But in the end we have him [as] Butch Cassidy. [Laughs.]

How did Sam Shepard become involved?

I thought Sam Shepard was perfect for the part, but I confess I never knew how to talk to him. First, my English is not very accurate; sometimes it was difficult for me to explain. But farther [sic] than that, sometimes I feel a difference between Americans and Europeans in the way we express our ideas. So I never was confident about the way I should speak to Sam, so I am always doubting between being very polite and being very direct. [Laughs.]

But he’s a very wise man, and I think he always knew how the character was better than me. My direction was mainly to explain to him very physical things like, “This is your gun; you come from here, you go there.” The rest was in Sam. The character was very clear, I think, fortunately, because if it wasn’t, it would have been very difficult for me to explain, you know?

Shepard is an intuitive and sophisticated actor, isn’t he?

Yes, but these are not very good times for actors like Sam. There is a new kind of cinema, and I think that it’s difficult for people like him to find good characters, in his style.

Think about Jeff Bridges, for example. I think his best character in many years is the movie with the Coen brothers [True Grit], because it’s an old style movie. I’m not saying anything about the movie, if it’s good or bad—I like it very much—but it’s a very classical movie. It’s a movie that looks very directly to the character, so for an actor like Jeff Bridges, it’s a gift. And I think Sam and Jeff Bridges are kind of similar actors in some ways.

But yes, I think he is very sophisticated. But in working, I think he’s strong, because he’s a writer. When he works, he wants very direct intentions for his character, and he doesn’t like to complicate too much the scenes or the character’s intentions. He likes to play straight, which is very good for Western movies, so we were lucky. We didn’t need to talk very much about the style or these characters. Everyone there was a great lover of Westerns, and everyone knew how to do his work. It was a very interesting film.

Televised Westerns

Hell on Wheels begins its run on AMC on November 6. It’s the story of a lone ex-Confederate soldier, working his way through a list of the men who killed his wife during Sherman’s March. The trail leads to the ever-moving construction site of the Union Pacific, as it works its way West.

TNT has ordered the pilot of Gateway, which has a revenge theme as well, but it’s also a brother story—three brothers, actually, coming to the 1880s Colorado town where their sheriff father was been killed. The responsible party seems to be the local land-and-power hungry cattle baron.

Former teen idol Shaun Cassidy is prepping an 1840s series called Frontier for NBC. The show follows Missouri emigrants headin’ West.

Ron Moore, ex-Star Trek: The Next Generation writer/producer, has a made-for-TV and potential series for ABC, Hangtown, about a reporter, a doctor and a marshal who solve crimes in the woolly West.

On Australian television, you’ll find Wild Boys, a good, gritty, action Western about a handful of bushrangers (outlaws) one step ahead of a murderous sheriff. American Western fans would enjoy this show; check out au.tv.Yahoo.com/wild-boys/ to see some video clips.

Henry Cabot Beck is the Film Editor for True West, writes about pop culture in general for other publications and is a member of the Phoenix Film Critics Society.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Magnet Releasing –

Blackthorn Director Mateo Gil