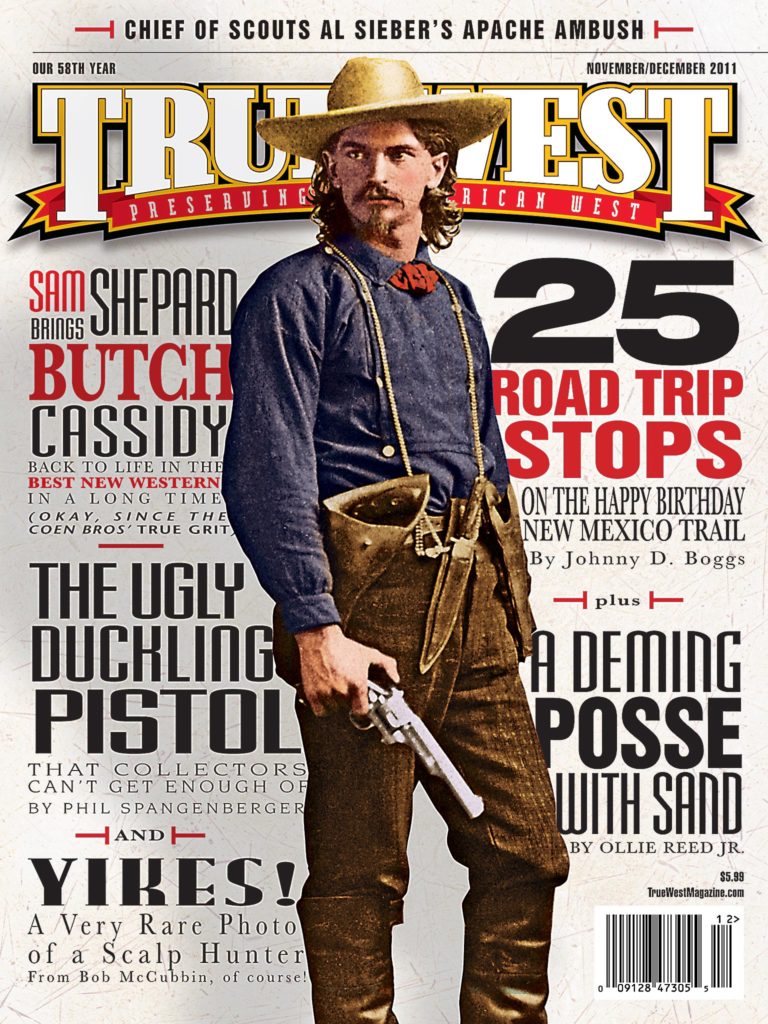

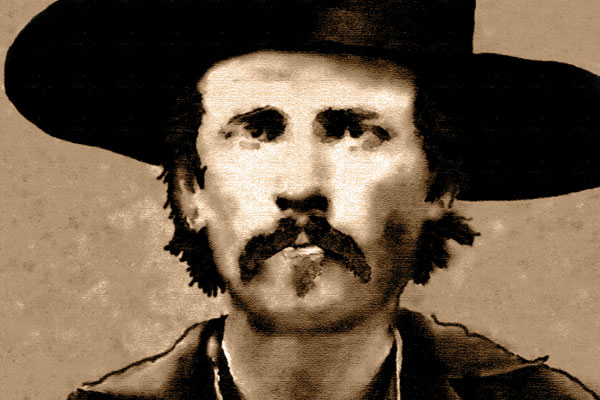

Ned Wynkoop risked his command to end an Indian war and exploded with rage when those same Indians were brutally hacked to pieces at Sand Creek.

Ned Wynkoop risked his command to end an Indian war and exploded with rage when those same Indians were brutally hacked to pieces at Sand Creek.

This changed him forever. He spoke out against Indian atrocities, turning him from a popular personality in Colorado Territory to perhaps the most hated white man in the territory. Shared here are five misconceptions about him.

1. Not everyone on the frontier hated Wynkoop.

I can name two people who didn’t hate him. Joking here, but not by much. Stand up for Indians, and the population grows fangs.

Those two people were Capt. Silas Soule and Lt. Joseph Cramer, Wynkoop’s 1st Colorado Volunteer Cavalry subordinates at Fort Lyon, Colorado Territory, in 1864.

Both were at the Big Timbers (Kansas) with Wynkoop when he met the Southern Cheyennes, Dog Men and Arapahos, and received four children in early September.

They were in Denver, on September 28, when the Indian leaders met with Gov. John Evans and Col. John Chivington (1st Colorado).

Finally, both were at Sand Creek on November 29, when Chivington and 1st and 3rd Colorado Volunteer Cavalries attacked the Cheyenne-Arapaho village—both refused to fire their weapons.

2. Wynkoop never ran from an Indian woman.

If you believe this, I’ve got some oceanfront property in Arizona I can sell you at a decent price. What do you think? Of course he ran from an Indian woman—he was human. Ye-ouhh—that’s a terrible thing to say!

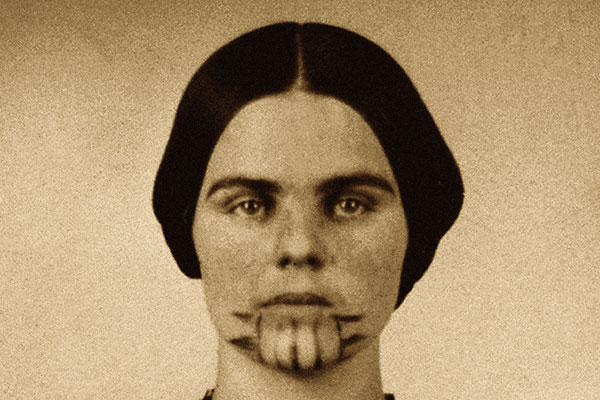

Here’s what happened: While working as a clerk in the Pawnee Land Office, Wynkoop and a few of his coworkers were strolling down a dirt road in Paola, 45 miles southeast of Lecompton, Kansas, when a drunken, mounted Miami Indian woman attempted to ride over them, changing directions whenever she missed one of the men.

Wynkoop leaped onto a wooden fence and, thinking he was safe, used his fingers to direct an ungentlemanly comment at the woman. She charged him and pointed a pepper-box pistol in his face. Thinking he was about to get shot, Wynkoop flipped over backwards onto the grass and began rolling. When she didn’t shoot, he got up and ran.

When Wynkoop next saw his comrades, he implored them not to tell the story. Fat chance, for they couldn’t wait to tell anyone who would listen. Wynkoop later said, “I have never run from a squaw since.”

3. A horse fell on Wynkoop during Capt. Soule’s funeral procession in Denver.

A horse did buck and fall on Wynkoop … but not during Capt. Silas Soule’s funeral procession in April 1865. A horse did rear up, Wynkoop tried but failed to control the animal, and it fell on him during a funeral procession as it crossed over Cherry Creek on the Larimer Street bridge in early February 1863.

4. Wynkoop instantly became an Indian lover, when Chief Black Kettle wrote to Fort Lyon stating he wanted to end the war.

Hate to say it, but on that fine day, September 4, 1864, Wynkoop considered Indians little more than animals … a harsh statement, but true.

Still, some diehards insist that Wynkoop miraculously turned Indian lover. They quickly point to an incomplete draft of a memoir that Wynkoop started in 1876, wherein he wrote, “I was bewildered with an exhibition of such patriotism on the part of the two savages, and felt myself in the presence of superior beings; and these were the representatives of a race that I heretofore looked upon without exception as being cruel, treacherous, and blood-thirsty….”

Love at first sight? Perhaps he was trying to justify his actions—his subordinates called it a suicide mission—of acting without orders, meeting warring Indians, obtaining four white children and taking seven Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho chiefs to Denver to talk about ending the war.

After that September 28 meeting, Rocky Mountain News publisher William Byers, the Indians and Wynkoop thought peace would return to the land, once military authorities made a decision. But after the Arapahos camped near Fort Lyon and the Southern Cheyennes camped farther away, Wynkoop admitted, “…I could at any moment, with the garrison I had, have annihilated them had they given any evidence of hostility….”

Doesn’t sound like love at first sight to me.

5. The Southern Cheyennes loved Wynkoop for all he did for them.

Not quite. For example, in April 1867, when Wynkoop was a U.S. Indian agent, he did everything possible to prevent Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock from marching toward a joint Southern Cheyenne-Sioux village on the Pawnee Fork in Kansas, saying the Indians feared being killed. Hancock refused to listen, and when his massive army of some 1,300 men approached the village, the Indians did exactly as Wynkoop said: they deserted their homes.

Of course they were guilty of something, Hancock reasoned, for why else would they run? Wynkoop warned Hancock that if he destroyed the village, he would start another war. Hancock ignored Wynkoop, destroyed the village and started a war.

Now here’s the rub: Even though Wynkoop had done all he could to save the Indians’ homes and belongings, the famed Southern Cheyenne war leader Roman Nose blamed him for Hancock’s actions. Before the Medicine Lodge Creek peace council began in October 1867, Roman Nose and about 10 warriors slipped into the encampment, intent upon killing Wynkoop. Luckily, Arapahos warned him of the danger; he leaped onto a horse and raced to Fort Larned and safety.