“I want to continue the traditional methods and designs,” Tonita Hamilton Nampeyo said.

“I want to continue the traditional methods and designs,” Tonita Hamilton Nampeyo said.

“I don’t want to deviate from what my mom [Fannie Polacca] and grandmother [Nampeyo] did and hand it down to the young ones. That’s the most important thing, to keep tradition alive.”

The Nampeyo family was featured in “Seven Families in Pueblo Pottery” at the University of New Mexico’s Maxwell Museum of Anthropology. Before that 1974 ground-breaking exhibit, collectors knew of only two Pueblo pottery artists: Nampeyo, whose work was first recognized after an 1891 archaeological dig at Sityatki, and Maria Martinez, of San Ildefonso, whose work was inspired by pots uncovered at a 1908 excavation.

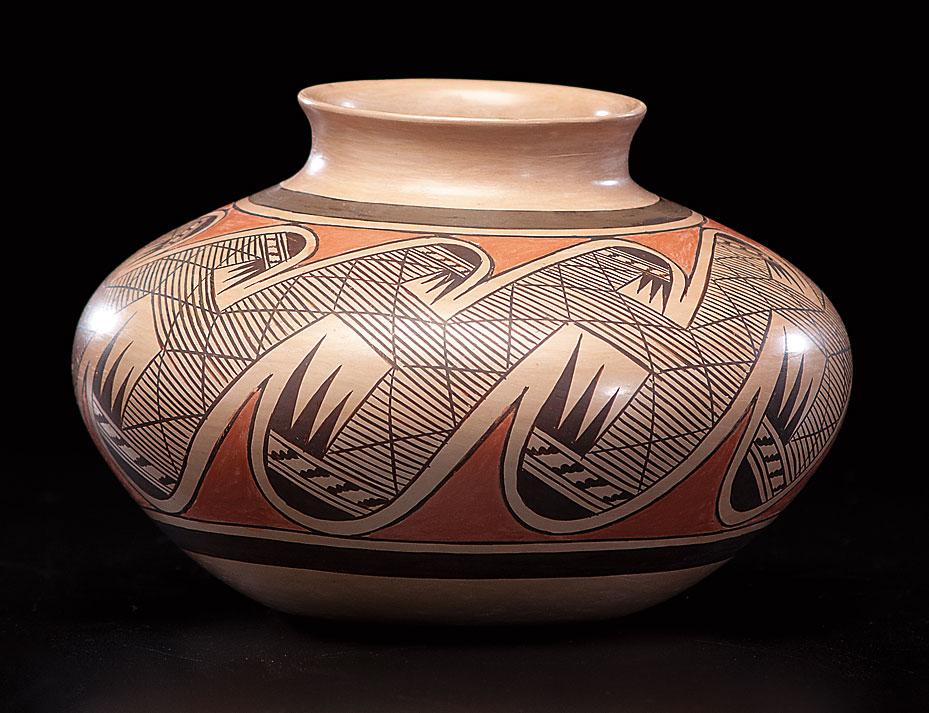

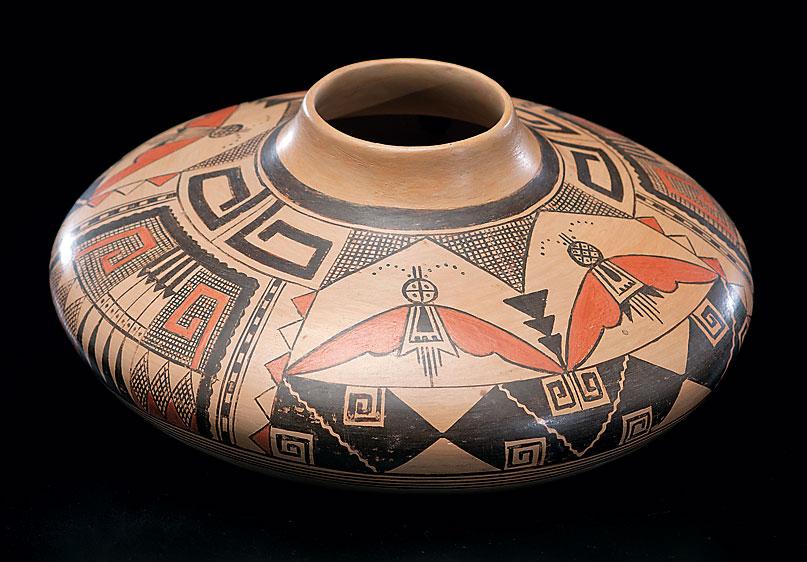

For her pots, Tewa-Hopi potter Nampeyo (born around 1860) revived designs she had seen from Sityatki, such as the bird claw and the cross hatching that referenced Hopi migration patterns. She was also encouraged to portray Hopi katsina designs on the pot, likely from Thomas Kearn, who had established his trading post at First Mesa in 1875.

Yet what mattered most to Nampeyo, and other Pueblo potters, was maintaining the tradition of making the pots, not the pots themselves. “…a potter’s skill is never ‘sold,’ it is not a commodity,” wrote W. Jackson Rushing in Native American Art in the Twentieth Century.

What Nampeyo passed down to her four daughters—Annie, Cecelia, Fannie and Nellie—was the coil-and-scrape method her ancestors had utilized to make their pots. She showed them how to collect shards of clay, ground them down, pound a ball of clay into a base and build the sides of the vessel by coiling a rope of clay upon itself in a spiral. After she shaped the pot, smoothed it with a stone, covered it in a slip and painted the design, the pot was fired in a kiln of stone and animal dung.

The legacy that Nampeyo, who died in 1942, would be most proud of is how her pottery has inspired nearly 75 members of her family to take on pottery making as their vocation.

At the Cowan’s American Indian and Western Art auction on September 9, 2011, not only did Nampeyo pots go up for bid, but also pots from other Pueblo families popularized in the 1970s. Cowan’s auction closed at more than half a million dollars.

Photo Gallery

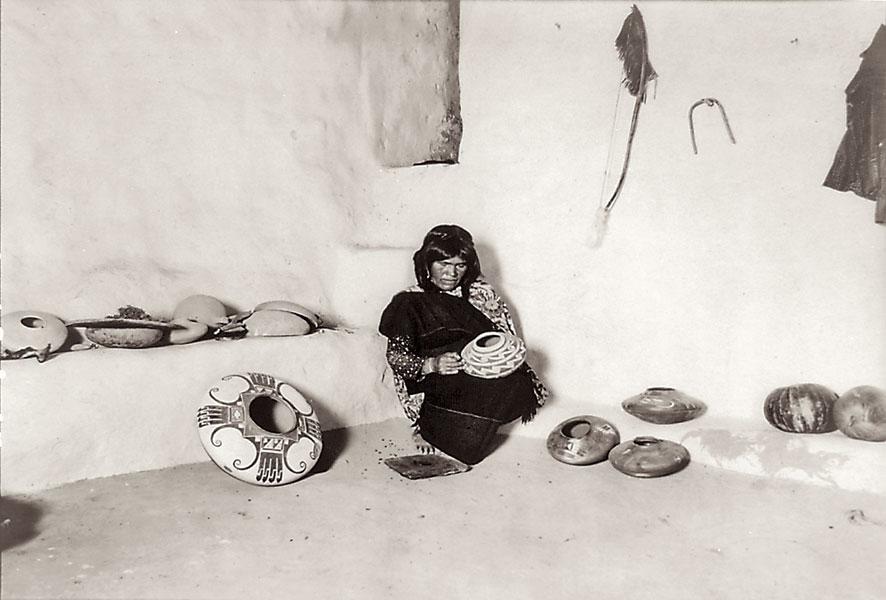

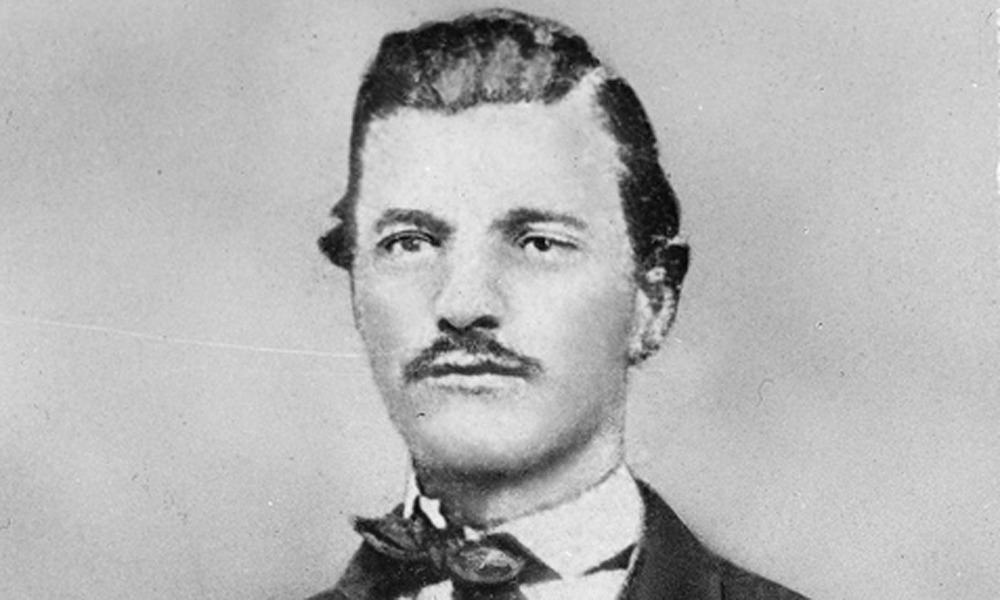

A noted Tewa-Hopi potter of the Hano pueblo in northeastern Arizona, Nampeyo is shown decorating pottery in the 1903 photograph by Homer Earle Sargent Jr.

–All images courtesy Cowan’s Auctions–