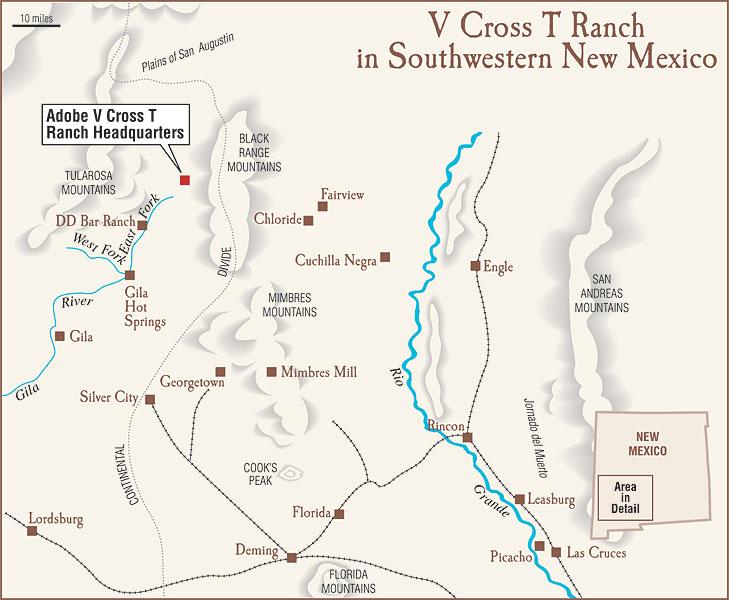

ADOBE RANCH, N.M. Out here, where the tawny Plains of San Agustin spill over the Continental Divide and slap up against the mountains of the Black Range, spring winds rowdy enough to rattle your teeth, blister your ears and curb your enthusiasm whip it up wild, loud and persistent.

ADOBE RANCH, N.M. Out here, where the tawny Plains of San Agustin spill over the Continental Divide and slap up against the mountains of the Black Range, spring winds rowdy enough to rattle your teeth, blister your ears and curb your enthusiasm whip it up wild, loud and persistent.

But on this day, a Friday afternoon in early May, the wind has backed off for a bit, gentling down to an earnest breeze that ripples the grass on the Adobe Ranch, which lies 50 miles, as the crow flies, southwest of the old cowtown of Magdalena.

Cooter and Beans, the Adobe Ranch dogs, are prowling among the rusting wire and weathered pine planks of the ranch’s ancient corral, sniffing eagerly at discarded horseshoes and junked truck beds as if they hadn’t seen or smelled these things just about every day of their lives.

The Adobe Ranch, more than 150 years old, is still a working cattle ranch, running stock with the V Cross T, Slash or Rafter I Bar brands. Ginger Whetten, wife of ranch manager Gene Whetten, thinks the corral dates back 100 years or more.

Maybe so. Gapped and sagging in places, the corral fences no longer hold stock. And instead of cowponies, the old stalls shelter used-up ranch equipment and worn-out ranch house appliances.

But if this corral is 100 years old, it has surely got a lot of ghosts penned up in it. On November 17, 1911, these fences might have played a supporting role in the gunfight at the V Cross T corral, one of the bloodiest battles between lawmen and lawbusters in New Mexico history, and a fight every bit as lethal and lead-infused as the 1881 showdown near that other corral over in Tombstone.

When the V Cross T corral gunfight was over, three men—including two peace officers—were dead. It happened right here. But it started 100 miles south, in the Luna County seat of Deming.

On the evening of November 7, 1911, 10 days before the fight at the V Cross T, Luna County Sheriff Dwight B. Stephens was reading the paper in his jail offices in Deming. It was election day, and Stephens, a Republican, was trying to keep a cool head as he waited to see if he had won re-election over his Democratic challenger.

Governor Miguel Otero had appointed Stephens sheriff in 1904 to fill out an unfinished term in this Southwestern county which borders Old Mexico. Stephens was then elected to the office in 1905 and 1909. This election, however, was different from the others because the New Mexico Territory—finally overcoming arguments that it was too corrupt, too Hispanic and too violent—was set to become the nation’s 47th state on January 6, 1912. Officials elected in this November election would be the first to serve the new state government.

Stephens won the election by more than 100 votes. But before he even heard the good news, his evening was spoiled by a masked man who climbed over the nine-foot-high adobe wall surrounding the jail and introduced Stephens and Chief Deputy James Kealy to the business end of his Winchester rifle. The masked man took Stephens’ shoes, guns and ammunition, and forced the release of a prisoner who was being held on a burglary charge, John W. Gates. The masked man and Gates then joined a third man, also masked, who was holding three horses outside the jail. The three mounted, kicked dust and were gone.

Officials suspected Gates was a member of the John Greer outlaw band that had been robbing trains, mail stages and saloons in southwestern New Mexico during the previous year. That suspicion was well-founded because the masked man who climbed over the jail wall turned out to be none other than John Greer, a bad man who was also wanted for the murder of a saloon owner, Charles Graham, in El Paso, Texas.

The second masked man was Reynold Greer (also known as William Randall), John’s younger brother, according to accounts published in 1913 in both the Albuquerque Morning Journal and the Albuquerque Evening Herald. Those same newspapers reported that the Greer brothers and Gates were among the Americans who had served with the rebel army of Francisco Madero and Gen. Pascual Orozco in the Mexican Revolution.

When John Greer was wounded in the March 1911 battle of Casas Grandes in Chihuahua, Mexico, Gates rode to his side, held off the advancing enemy with withering rifle fire, pulled the wounded Greer across his saddle and carried him to safety. Gates took Greer to a cabin north of the border and cared for him until he recovered. When Greer climbed that wall and busted Gates out of the Deming jail, he was keeping a promise to repay Gates—no matter what the cost.

Considering their experience in Mexico and the fact that the border was just 30 miles from Deming, Gates and the Greer brothers were likely to spur south. Maybe that’s why they rode north instead. Not fooled, Stephens and his posse—on mounted horseback, as were the outlaws—soon picked up the outlaws’ trail and followed it 40 miles north to the Black Range. A chase that would continue through rough country for nine days was underway.

Riding with Stephens were deputies W.C. “Bill” Simpson of Deming; Thomas H. Hall, who ranched near Deming; and A.L. Smithers, who was new to the Deming area and worked with the Cattle Sanitary Board. Along the way, Johnnie James, who worked a ranch near the Sierra County mining town of Chloride, joined the posse.

Drawing on wily ways learned while fighting in Old Mexico and riding the outlaw trail in New Mexico, the fugitives stayed in or close to the mountains and traveled mostly at night. They were well-mounted, well-armed, rode with a pack horse and supplemented their supplies by stealing from ranches and residences along the way.

As tough and savvy as they were, the fugitives failed to shake their pursuers. Both Hall and Stephens, an Ohio native who had lived in Luna County for a dozen years and had worked as a cowman and a railroad man before becoming sheriff, were highly regarded as trackers.

And, according to one source, the posse had an extra element working in its favor. This source, J.R. “Chief” Galusha, was a veteran lawman who had been a member of the New Mexico Territorial Mounted Police, a deputy U.S. marshal, a Santa Fe Railway special officer and an Albuquerque police chief. Galusha did not take part in the pursuit of the Deming fugitives, but he was a friend of posse member Simpson and heard stories about the chase.

In 1953, Galusha told Albuquerque Tribune reporter Howard Bryan that Reynold Greer’s dog was with the outlaws, so all Stephens’ posse had to do was follow the trail marked with both horse and dog tracks.

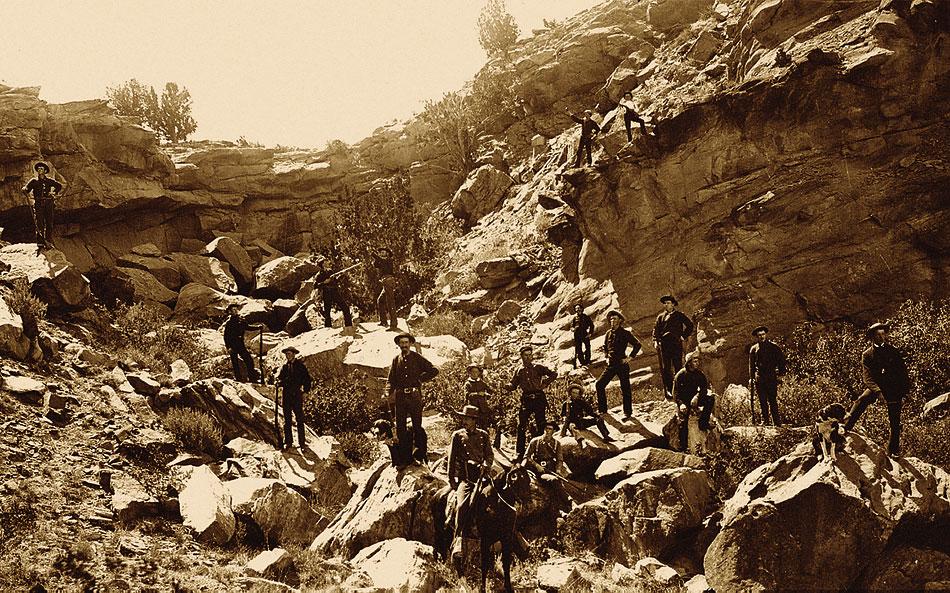

On November 17, a Friday, the posse gained enough ground on the fugitives to catch sight of them. The lawmen followed their quarry as the outlaws dropped out of the mountains and rode to the Adobe V Cross T Ranch headquarters. The outlaws, finding no one at the ranch and apparently not realizing how much ground the posse had gained on them, settled in to eat, rest up and pilfer more provisions.

Coming up on the ranch, posse members were unable to pick out the hunted men or their mounts among the headquarter buildings. The lawmen split up as they rode down to the ranch, Simpson and James stayed on the trail leading from the mountains to the ranch house, while Sheriff Stephens, Smithers and Hall rode east and came back at the ranch house from the north.

About 400 yards northeast of the ranch house, Stephens left Hall and Smithers to take a closer look at the house. About this time, Gates and the Greer brothers, leading their horses out of the V Cross T corral, saw Hall and Smithers sitting on their horses in the distance.

Holding their nerves in check and hoping, perhaps, that the deputies were cowboys returning from work on the range, the fugitives mounted up and rode slowly and calmly toward the lawmen. When Gates and the Greers were about 75 yards away, Deputy Hall called on them to surrender. That’s when things exploded like a bad bronc out of a rodeo chute.

Galusha told reporter Bryan that John Greer galloped straight at Hall and Smithers, a blazing six-gun in each hand and the reins in his teeth. Yet newspaper accounts at the time reported that the three outlaws swung to the ground and, using their horses as shields, fired rapidly over their saddles at Hall and Smithers while the deputies returned the fire.

What we know for sure is that Smithers was killed instantly by a bullet through the body, and Hall, after emptying his rifle at the fugitives, was killed by a bullet to the head.

Hurrying from the side of the house to join the fight, Sheriff Stephens, ignoring a squall of lead, put a rifle bullet into John Greer’s neck, killing the outlaw leader. “Sheriff Stephens … made one of the villains bite the dust altho [sic] bullets whizzed by his head thick and fast,” the Deming Graphic newspaper reported on November 24.

Stephens might have found himself chewing dirt as well if Simpson and James had not galloped into the fray, unleashing a volley that had Gates and the younger Greer scurrying for cover.

The fight had started late in the afternoon, about 4 p.m., and the outlaws had enough ammunition to keep the surviving posse members pinned down until darkness allowed them to slip away into the mountains. Gates and young Greer were on the run again.

Before dawn the next morning, Stephens, Simpson and James put the three bodies in a borrowed wagon and started out for the railway stop at Engle, 85 miles to the east. At Engle, the dead men were put on a train that arrived in Deming on Monday, November 20. Smithers’ body was sent on to his family in Amarillo, Texas, and Greer’s to his people in Lincoln County, New Mexico.

The Deming Headlight reported that a “tremendous crowd” attended Hall’s funeral in that town. Hall, 47, was survived by a wife, four sons and a daughter. He was buried in the Deming cemetery. “Thus ends the sad, tragic story,” the Headlight printed. “Thus closes another chapter in the history of crime and the manly, heroic efforts of brave, manly men endeavoring to uphold the majesty of the law.”

Epic words. But wrong. This was not the end of the story.

After the fight at the Adobe Ranch, posses hunted Gates and Reynold Greer throughout the Black Range and the surrounding area, but without success.

Reynold Greer was apparently never captured and certainly not convicted for his role in the jailbreak and V Cross T corral gunfight. The April 25, 1913, edition of the Albuquerque Morning Journal describes Reynold Greer as the “only one of the trio of bandits to escape and still be at liberty following the battle at the Adobe Ranch.”

In 1953, veteran lawman Galusha told reporter Bryan that the younger Greer served in the armed services during WWI and died in the 1918 flu epidemic.

But Gates, whose real name was apparently Irvin Frazier, was arrested in El Paso, Texas, in late December 1911 after trying to pawn a handsomely engraved handgun identified as one taken from Sheriff Stephens during the Deming jailbreak.

Gates—or rather Frazier—was tried in Socorro, New Mexico, for his part in the deaths of Hall and Smithers. The trial was held in Socorro because the V Cross T corral fight happened in Socorro County. Convicted after what the Deming Headlight called one of the briefest trials in New Mexico history, Frazier was sentenced to be hanged on April 25, 1913, in Socorro.

But that was not the end of the story either.

Because of his slippery reputation and the fact he had outlaw friends on the loose, Frazier was confined at the New Mexico State Penitentiary in Santa Fe while awaiting execution. Never one to give up, he smuggled a letter, likely intended for Reynold Greer, out of prison. In the letter, he outlined an audacious plan for rescuing him from the train that would transport him from Santa Fe to his hanging in Socorro.

Frazier’s plot called for Reynold Greer to put one of his men on the train when it stopped in Albuquerque and to have the rest of the Greer gang lying in

wait at La Joya, a station 20 miles north of Socorro, “where they were to hold up the train and take [Frazier] from the officers no matter what the cost,” reported the April 25, 1913, edition of the Albuquerque Morning Journal.

Did Reynold Greer, or any of the Greer family, or any of the Greer gang get the letter? Who knows? What is known is that the letter ended up in the hands of the authorities.

When the hanging train left Santa Fe on April 24, 1913, with Frazier and Francisco Granado, a convicted murderer, 18 well-armed lawmen were on board, including our old friend Galusha, who was a special officer with the Santa Fe Railway at the time. Anyone trying to stop that train would have paid a high cost indeed.

No one tried. Probably not until after the train passed La Joya did Frazier realize he was a done dog. The train arrived in Socorro after midnight. Before dawn, Frazier and Granado were taken to the second floor of the Socorro County courthouse, where a trapdoor had been cut in the floor to facilitate the hanging.

Frazier went to his death calmly, reported the Albuquerque Evening Herald; he even requested the hangman draw the noose a “trifle tighter.”

Sheriff Stephens, the hero of the gunfight at the V Cross T Corral, continued to serve Luna County as a popular and effective sheriff for several years after that bloody battle.

Then on February 20, 1916, those wild and violent ways that had prompted some people to object to New Mexico’s statehood in years past rumbled to the surface in the shape of yet another breakout from the Deming jail.

It was a Sunday, and Sheriff Stephens was not at the jail when several prisoners managed to overpower the jailer, taking his keys and guns. Then —since things had come a long way since 1911—the escapees, pretending to be deputies, used the jail phone to

call the Deming Ford dealership and order a fully-fueled car delivered to the jail. They told the Ford dealer they needed to transport a sick prisoner to a medical facility.

Five escapees left in the Ford, getting more than an hour’s head start before the jailbreak was discovered and a pursuit organized. Witnesses told Stephens that they had seen the Ford heading northeast when it left town, so the sheriff and five other officers piled into a car and set out in that direction.

They caught up with the escapees in an arroyo near Rincon, a Dona Ana County town 50 miles northeast of Deming. The fugitives, apparently having confused their escape attempt with a picnic, had stopped in the arroyo to eat lunch.

In the showdown that followed, Stephens walked around the base of a hill and to within 10 feet of the fugitives, one of whom killed him with a single shot from a .30-40 Winchester rifle. The bullet slammed into the sheriff’s shoulder and then slanted down into his heart.

One of the escapees was also killed in the gunfight, and all were eventually recaptured. Two were sentenced to be hanged for the sheriff’s murder, but neither ever was, both presumably served long prison sentences instead.

Sheriff Stephens, 43, was survived by a wife and four children, and was much mourned. The entire Deming community attended his funeral.

He was buried in Deming’s Mountain View Cemetery, not far from the grave of Thomas Hall, one of the deputies killed in the 1911 V Cross T corral fight.

Bill Simpson, who had also been in the 1911 fight and had later helped track down the 1916 escapees, was appointed to succeed Stephens as Luna County sheriff. The last survivor of the V Cross T corral gunfight, Simpson died in Deming in 1959 when he was about 74 years old.

The old Deming jail, blamed by the Santa Fe New Mexican newspaper for the tragedy of Stephens’ death, did not long survive the slain sheriff. The New Mexican article noted that two jailbreaks had occurred within a few years, both with disastrous results, and that the jail was likely the only building in Deming that the “citizens are ashamed of….”

Deming’s citizens got a new jail in 1918, and the old building was eventually demolished. Today, a Snappy Mart convenience store stands where the old jail once did. You can buy chips and soft drinks and bags of ice on the ground where life and death dramas unfolded 100 years ago.

The bloody V Cross T shoot-out came to a deadly climax 100 miles north, near the weathered planks and twisted wire of the Adobe Ranch corral. But it started right here, in the Luna County seat of Deming.

Ollie Reed Jr., a former newspaper columnist for The Albuquerque Tribune in New Mexico, is the marketing director for Western Writers of America.

Photo Gallery

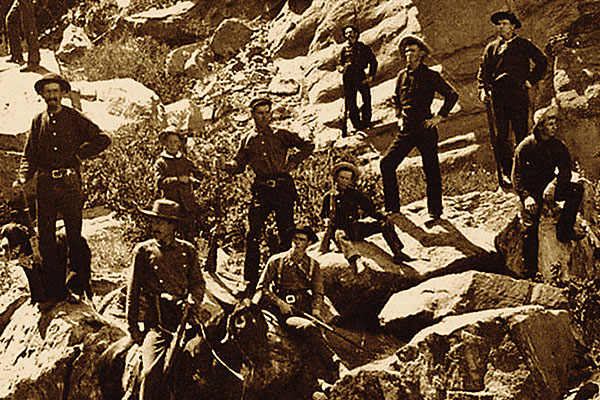

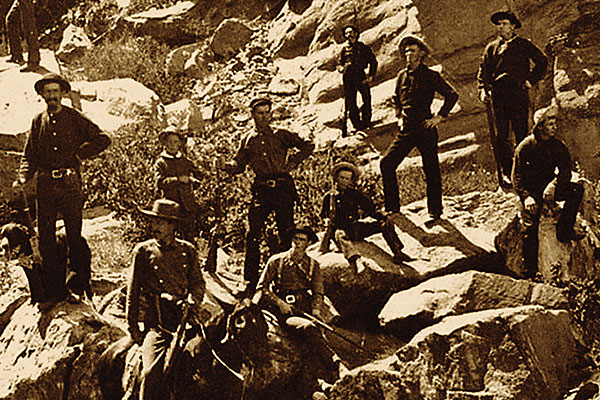

Joseph E. Smith, a former rancher-turned-photographer in 1884 Socorro, New Mexico, took this undated photograph of armed men and their dogs in the wilds of New Mexico. The dogs remind us of Reynold Greer’s dog, who accompanied the outlaws on the trail.

– True West Archives –

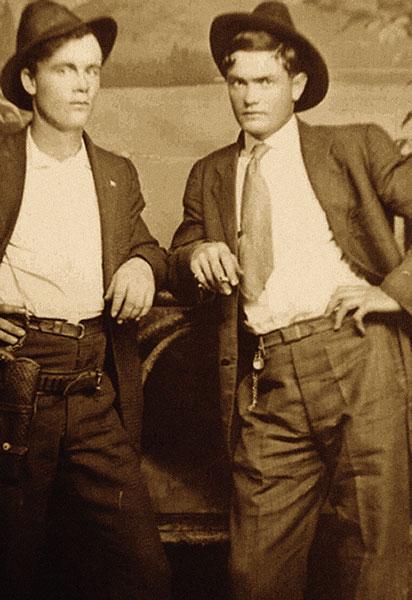

– Courtesy Luna County Historical Society –

– Courtesy Luna County Historical Society –

– By Margaret L. Wright –