It was the autumn of 1962, and we had just returned from a two-year duty tour in Taiwan.

It was the autumn of 1962, and we had just returned from a two-year duty tour in Taiwan.

The Old Man had decided to retire from the U.S. Air Force, the only real job he had ever held. Twenty-two years and two wars meant little to him now, but the retirement pay looked mighty attractive to a top sergeant whose stripes had been stripped away in a fog of drink and arrogance. Now he headed home to Indiana to start over in mid-life. We waited near Grissom Airbase, renting a rambling farmhouse outside of Kokomo, as the cogs of the bureaucracy worked their magic. It was a long wait since the Air Force had lost his paperwork and no retirement pay was forthcoming.

I remember that old house as cavernous. It was empty since our furniture from Asia never caught up with us—yet another gift from the government. We slept on cots and listened to a little radio posted in the big living room. The radio was important for that October brought the Cuban Missile Crisis. I was not in school. My parents assumed our stay would be brief, and I spent my days listening to the news bulletins. I sensed the uneasiness of the adults. They were burdened enough with the problems of the retirement snafu and lack of money, but the news seemed to dominate even those cares. The Old Man spent his days at the airbase trying to get his money rather than getting a job somewhere else. Of course the Air Force was busy with other matters. I spent my days sitting in the empty house with my mother listening to the radio and wondering if Kokomo was important enough for a Russian nuclear strike.

Odd how I focused on the crisis—times were tough, even for a 12-year-old kid. We had no money at all, and the little that came our way the Old Man spent on beer. He had a great thirst, and probably good reasons for it—a lifetime of bad choices and missed opportunities. I didn’t understand then, but the passing years do give perspective. The immediate problem that October was eating, as well as avoiding Soviet missiles. We ate a lot of peanut butter and jelly sandwiches—lunch and dinner. By late October both the international crisis and the family crisis had worsened considerably.

My birthday was October 23rd. Somehow my mother acquired a little ham with a big bone that she used to make wonderful soup that we fed on for a week or more. The ham provided my birthday supper. It was quite grand sitting in the middle of the big empty living room floor eating that meal. I expected no gift—and was quite surprised to receive one. It was not wrapped in paper, but a cloth ribbon had been lovingly placed around it by my mother. It was not a permanent gift, but only on loan, because my mother had gone to the Kokomo library and selected a book for me to read.

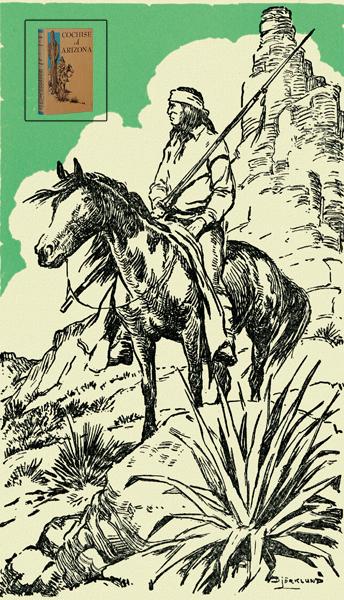

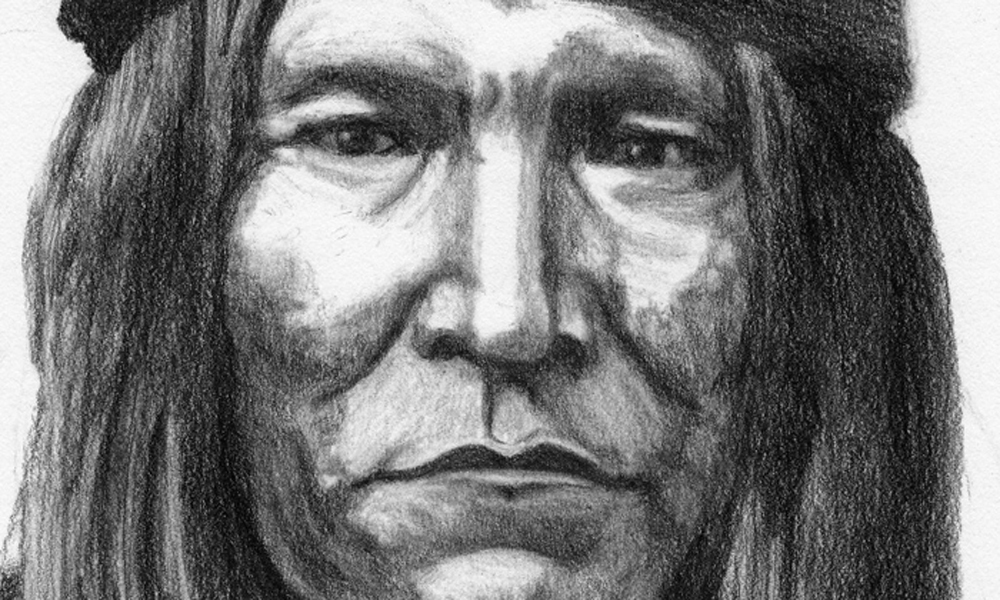

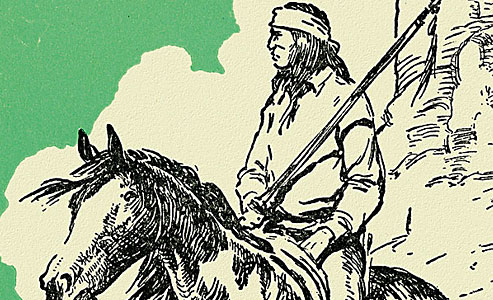

It was a beautiful book—bound in tan cloth with light blue embossing. A mounted Indian warrior adorned the cover. It was illustrated with wonderfully fluid line drawings—full of action and high adventure. I could not put it down, and in fact read it several times over before it had to be returned. It was the story of Cochise, the magnificent Chiricahua chief, and of his friendship with the enigmatic white man Tom Jeffords. This tale of betrayal, warfare, friendship and finally redemption caught my imagination. I learned from it the complexity of a Western past that I had previously seen only in simple terms. I learned that heroes can fight boldly for peace as well as gallantly for victory. And I learned about the vital importance of loyalty and friendship. I never forgot that book—the story and the illustrations replayed over and over in my mind.

There would be many more books. The first novel I read was Elliott Arnold’s Blood Brother, obviously the inspiration for my birthday gift book. In time I found another copy of my birthday book—Oliver La Farge’s Cochise of Arizona. The mint copy I purchased was even inscribed by the author who I had by then learned was an important writer on native America. The illustrations that I had so loved as a child were by Lorence F. Bjorklund, whose work I collected for years without realizing that he was the illustrator of the birthday book.

Today, in a house crammed full of books, many dearly loved as touchstones to a living past, no book is more prized than La Farge’s Cochise of Arizona. I only wish I still had that dog-eared copy from the Kokomo public library—that perfect symbol of a mother’s love—that perfect gift during a distant autumn of fear and want.

Paul Andrew Hutton’s latest book, Western Heritage: A Selection of Wrangler Award-Winning Articles (University of Oklahoma Press), was published in April 2011.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Paul Andrew Hutton –