Hugh O’Brian is Wyatt Earp. By that I mean that in talking with O’Brian, one gets the sense that the actor is in many ways as contradictory as the legendary lawman Earp has become over time.

The irony is that because O’Brian’s Earp is “brave, courageous and bold,” as the theme song endlessly reiterated, historians are up against this stiff-backed, morally righteous version of Earp whenever they try to humanize the real-life Earp, or in a few cases, demonize him.

One also gets the sense that O’Brian has kept Earp on hallowed ground, and he has possibly made some effort to represent Earp’s reputation in the way he’s maintained his own life.

Certainly O’Brian’s charity work is well-known and widely respected. The organization he started in 1958, HOBY (Hugh O’Brian Youth Leadership), continues to do good work training future leaders across the globe.

The real man who O’Brian portrayed from 1955-61 in the ABC series The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp was many things to many people, and not all of them particularly laudatory. Wyatt Earp, who died in Los Angeles in 1929, was probably a good deal more interesting in real life than as he was portrayed by Henry Fonda, Burt Lancaster, Randolph Scott and other stars throughout the decades.

The same can be said of O’Brian.

Most biographies of O’Brian usually start here: Born Hugh Charles Krampe in 1925, O’Brian was raised in a marine family and became the youngest drill instructor in marine history, in 1943, at 17.

He likes to tell the story of how he got into the ring, on base, with a huge fighter, and how he barely managed to win the fight, which just happened to have been refereed by the visiting actor John Wayne. That story ties in neatly with the fact that O’Brian was the last person killed in a gunfight with Wayne on camera, in Wayne’s final movie, The Shootist.

While still in the service, O’Brian won a contest on a radio show by going off-book and improvising a line, which landed him a date with the stunning movie star Virginia Mayo and a wild night on the town at the famed Coconut Grove, where Tommy Dorsey & His Orchestra was performing. That he remembers anything at all is remarkable, because he was introduced to a virtual chorus line of Brandy Alexanders by actress Arlene Francis.

The next day O’Brian was invited to visit a set, where he was introduced to a real chorus line of tasty starlets, the Goldwyn Girls, who were appearing in the 1945 feature film, Wonder Man, starring Mayo and Danny Kaye.

Says O’Brian, “Ever hear about them? Each one was more beautiful than the other, each one of them built like a brick s—house. As I used to say, they were all test pilots for Borden Milk. In other words they had big—”

“I got it,” I told him.

O’Brian takes nearly as much pride describing how he stumbled into a career as a movie and TV actor as he does his marine years, but it’s good stuff, and it involves his moving in and working with a house full of these hot Hollywood hopefuls, which, he will tell you, tested his athleticism to a dangerous degree.

He admits he got the obligatory lucky breaks: sick actors who required replacing, a fantastic audition for Director Ida Lupino that netted him an important role and a succession of small-getting-bigger parts in pictures in the late 1940s-50s.

O’Brian can be a moderately tough interview, not so much because of his age, but because his hearing was compromised as a result of the loud gunfire on the series. “I insisted on using full loads, instead of quarter loads, [which were] just enough to get a bang and some smoke out the end of the pistol. But I wanted the guy in front of me to really feel the pressure of a live .45, and whether they were getting paid or not, they fell down.”

O’Brian is alternately righteous and raunchy, tough and entertaining, how I like to imagine the real Wyatt Earp might have been, back in the 1920s, over a poker game or on a cool Los Angeles evening. Although O’Brian interrupted our initial conversation so that he could attend a screening of Wolverine at the Playboy Mansion, he gave me enough material for several interviews, and I have no doubt he has plenty more to give.

Hugh O’Brian: You know what the title of my book’s gonna be? The Older I Get, The Better I Was [laughs].

Henry Cabot Beck: I wanted to tell you how much I’ve been enjoying watching the first season of Wyatt Earp. They’re damn good shows.

Well thank you. We had very little time to make them, and you really had to know what the f— you were doing, because very rarely would we have time for a second take. And the other thing was the always-continuing battle for authenticity, and that had to do with the scripts and what the other people did. My own dialogue was one thing, but also getting [it] to try to be authentic with the other guy’s dialogue.

But I think I wound up with a lot of respect. Do you realize how much dialogue is in 18 pages a day? And when we began, it was a six-day week in show business. You did a film, TV, six days a week. Monday through Saturday. And with [Ronald] Reagan running the union, we [went on strike], and we got a five-day week. And the Wyatt Earp people said, “Okay you a–holes, you don’t want to work on Saturday? We’re going to do two shows in five days instead of six.” And so we would do Monday and Tuesday on show one, on Wednesday we’d go out to Autry [Santa Clarita] or wherever, and we’d shoot the exteriors for both shows, and on Thursday and Friday we’d shoot the interiors for the second show. Think about that, and not getting home until 7:30 at night, having to memorize 18 pages for the next day, and then getting up at 5:00 or 5:30 a.m., they’d pick you up at 6:00, and by 6:15, you’re out on the god—- set at RKO.

I never, ever had a dressing room, so you know what happened? Lucy was married to Desi, and they owned the RKO Studio. Lucy heard they didn’t want to spend the money to rent me a dressing room. She said, “You use my dressing room. Go embarrass those a–holes to where they pay for your own dressing room.” For six years I used her dressing room.

You know, the only way I made any money on Earp was I bought the company that supplied all the hardware, and eventually the wardrobe company, and by owning all of that, I made money on the show.

As I was watching your show, I started to realize that the movie Tombstone pulled a lot from the series.

I think they did a great job with both of those movies. Kurt Russell and Kevin Costner were both very good. The [films] were both very well done.

I’ve heard people say that they wish the series had a different Doc Holliday, or that your relationship with Holliday had been written differently.

I never heard that. Doug Fowley did the original on the show, and I thought he was very, very special. The next one—can’t think of his name right now [Myron Healey]—but he was not as tough and b—-y as the real Doc. I thought that Doug had the right snazzy b—-iness to be Doc Holliday.

When you look at Doc Holliday, he had his own agenda. And in many ways it’s a good thing that [he and Wyatt] befriended each other. They were totally opposite of each other, but they respected each other, and that’s the important thing. That’s why I think Doc came to his assistance.

Kirk Douglas once told me he saw the Doc and Wyatt story as a kind of a love story between those two guys.

I don’t think so—I think—depends on if you rephrase love story as respect. I think they understood each other’s territory, and they basically stayed out of that…. Wyatt Earp let Doc have his space, and I think that Doc understood that and respected him for that.

A normal guy would have kicked Doc Holliday out of town. For whatever reason, Wyatt saw his friendship in practical terms. From a business point of view, Wyatt was smart enough to want to have somebody on the other end on his communication list. He appeased Doc in many situations, because Doc had a contact, a communication, with the other elements. I think Wyatt was smart enough to embrace that and take advantage of it.

Do you mean that he had a conduit into the underworld through Holliday?

I think underworld is the wrong [term]. There were many people who went from city to city who were opportunists, and there were many people who lived there who weren’t crooks, but they would do things to make a buck. I think that Doc provided [Wyatt] a sounding board for the reality of what was in town and what was not in town. Doc spent a lot of time in the saloon; Wyatt did not…. Doc would be honest with Wyatt and say, “Hey man, you gotta watch out. There’s a new team in town and they are out to f— anybody, so keep your eyes open.”

I think they had a very practical working relationship, and each of them got something from it.

Since Earp died in Los Angeles in 1929, you must have met people who knew him.

A lot of people came on the set who knew Wyatt, people he befriended or who befriended him. He had a lot of friends and spent his last days living here.

Stuart Lake, the official chronicler of Wyatt Earp, is credited on the series. Did you spend much time talking to Lake?

Oh yeah. A lotta time. I think one of the reasons I got the role was because of Stuart’s push for that. He knew I was a marine, and he was a marine, and I think that had a lot to do with how I was selected.

Prior to the series, you were already getting work with top shelf directors and working with actors like Spencer Tracy. Things seemed to be working out for you.

Quite frankly it was a major decision as to whether I wanted to do a series. The reason I did it was certainly not for the money. The reason I did it was because I felt this could become, if we really went for reality, could become the first adult Western. And it was. The stories were actual; they were about people who lived. We did everything we could to make it authentic. I had to fight for that in many ways…. I went into Western Costume, and they [would have] the total opposite of what we’d talked about in terms of an outfit. They just didn’t wear polka dot shirts back then [laughs].

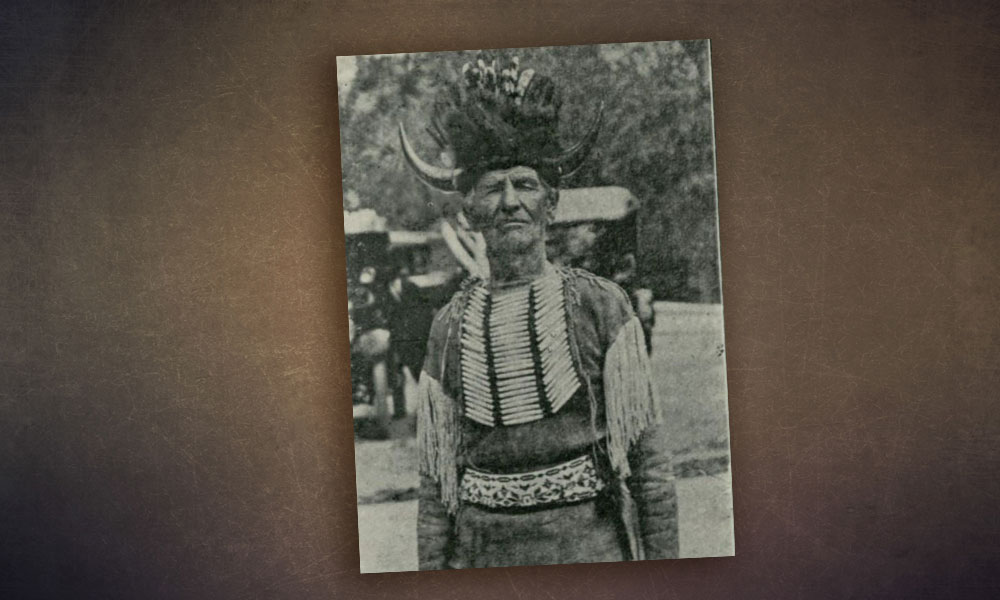

The wardrobe [they had picked out] for most of the shots when I was in Tombstone—the frock coat, the string bow-tie, the vest, that’s what the mayor wore, that’s what the judge wore, and that’s what the guy who owned the Longbranch Saloon wore. I just went in there and picked out everything I thought would look right, and I damn near lost the role for that. They were not too happy with it, and Stuart stepped in and said, “God—-it, the kid’s right. This is the kind of stuff [Wyatt] would have worn.” There weren’t any uniforms for the job, so he wore what the other city officials wore. I saw pictures of him with a flat black hat, and that became a symbol of that character. Visually, the Wyatt Earp character is one of the reasons the show became a success.

And the Buntline Special. I practiced the quick draw for maybe 500 hours. I would be in the mirror, cocking and firing, and I finally got so fast I could beat the guy in the mirror [laughs].

When Wyatt was walking around [Tombstone], he usually carried his rifle, but he was a peaceful guy. It’s just that he let it be known to anybody, and everybody knew it, you don’t want to f— up in this town; otherwise you’re going to come up against Wyatt.