If any man in 1901 had been asked about women in business, he’d have laughed and said they didn’t have any “business sense.”

If any man in 1901 had been asked about women in business, he’d have laughed and said they didn’t have any “business sense.”

Besides, women were too busy running the home and raising the children, they shouldn’t dirty their little dainty hands with something as competitive and ambitious as business.

No one could say that to Sarah Kidder. Her presidency of California’s Nevada County Narrow Gauge Railroad is known as its “Twelve Golden Years” because she made the line more profitable than it had ever been or ever would be—outdoing her late husband who built the line and the men who eventually bought her out in 1913.

Nobody is sure how this traditional woman—she believed that females should give the home “all their attention” and opposed suffrage—got such business sense or where she learned to make remarkable profits, but it was a good show by the first woman in the world to ever head a railroad.

Petticoat Railroading

Sarah Clark Kidder and her husband John were married in 1870 and soon moved to Grass Valley, California. John came to town as superintendent of a new railroad, but he soon bought it out and became the “most important man to the welfare and progress of Nevada County,” as he was eulogized in April 1901.

His lovely wife was known for her magnificent scroll-saw mansion with its beautiful flower gardens that hosted tea parties and other coveted gatherings. She volunteered for an orphan society and raised their adopted daughter Beatrice. Mother and daughter were known for wearing the lovely lace gowns Sarah sewed.

When John died, he signed over all his stock to his wife—giving her control of three-quarters of the capital stock. On May 7, 1901, Sarah was elected president of the railroad by a vast majority of the shareholders. She had very big shoes to fill.

Her husband had built the 22-mile line into a major economic force in Nevada County. The rail line originally hauled lumber, farm produce and gold destined for the U.S. mint in San Francisco, but it soon became popular with families who liked riding the rails along the exciting route into the mountains—over four trestles, around sweeping curves and through tunnels—and out to picnic grounds. It ran from Nevada City to Colfax where it connected with what is now called the Southern Pacific and was the main freight and passenger link outside the area.

John is remembered as a brilliant businessman, even though he never paid a dividend to his stockholders. During his 18 years at the helm, he expanded the line and paid off $14,000 worth of debt. More debt kept piling up, though, and a large hunk was unpaid at the time of his death.

Could Sarah measure up? Besides running her household, she’d never organized a payroll or managed a staff or kept a railroad running. She was shocked when she discovered that her husband had left the railroad company in debt.

“But Sarah overcame the blow and set out immediately to tackle the problem,” notes Nancy Smiler Levinson in She’s Been Working on the Railroad.

“First, she needed to pay off the debt. Then she had to move the company forward by earning higher profits. The most important action she took was to create new business by encouraging additional freight and passenger travel. From all reports, she was praised for doing a remarkable job in accomplishing her goals. In fact, by the end of 1903, hardly three years after her presidency began, the company’s annual report showed its best profit in its twenty-seven-year history.”

Or as Robert M. Wyckoff notes in Never Come, Never Go!: The Story of Nevada County’s Narrow Gauge Railroad: “Any tallowpot or gandy-dancer who might have looked for a letdown under petticoat railroading soon learned the error of his thoughts—Sarah was a stickler no less than John.”

He notes the line “continued to flourish” under her leadership—in fact, it did more than that; it broke all records.

Historian Maria E. Brower details Sarah’s accomplishments in a 2003 article in The Union: “She had steadily improved the railroad until it was said to be a showpiece of its kind and her years of management led the railroad into its greatest prosperity. She was able to pay off $79,000 in funded debt, paid $184,122 interest on that debt and declared $117,000 in dividends on the stock, and added $180,000 to the undivided surplus.”

Her successes were noted where it counted—in the banks of San Francisco where she went to seek a loan to build a new trestle for her line. Levinson notes it was a “bold action for a woman at that time” to even seek a bank loan. But she got it and rebuilt the trestle above the Bear River, which held the distinction of being the highest in the U.S. at 173 feet. (The trestle was torn down in 1963 to make way for Rollins Dam.)

Sarah also had to maneuver through a legal challenge to her ownership. The son of her husband’s former business partner claimed that his father had declared on his death bed that he and John Kidder jointly owned the stock. The son wanted half of Sarah’s stock. She fought him for more than a decade in the courts, where every judgment was in her favor. The case was finally resolved just before she sold her interest in the railroad.

After selling her stock in 1913, Sarah moved to San Francisco where she lived out her life. She died at age 94 in September 1933.

Sarah’s Memory Lives On

Thankfully, she didn’t live to see the ignoble end to the line she and her husband had worked so hard to operate. It was abandoned in 1942, a “victim of improved road transportation and rapidly rising operating costs,” Wyckoff notes. “The rails and ties were taken up.”

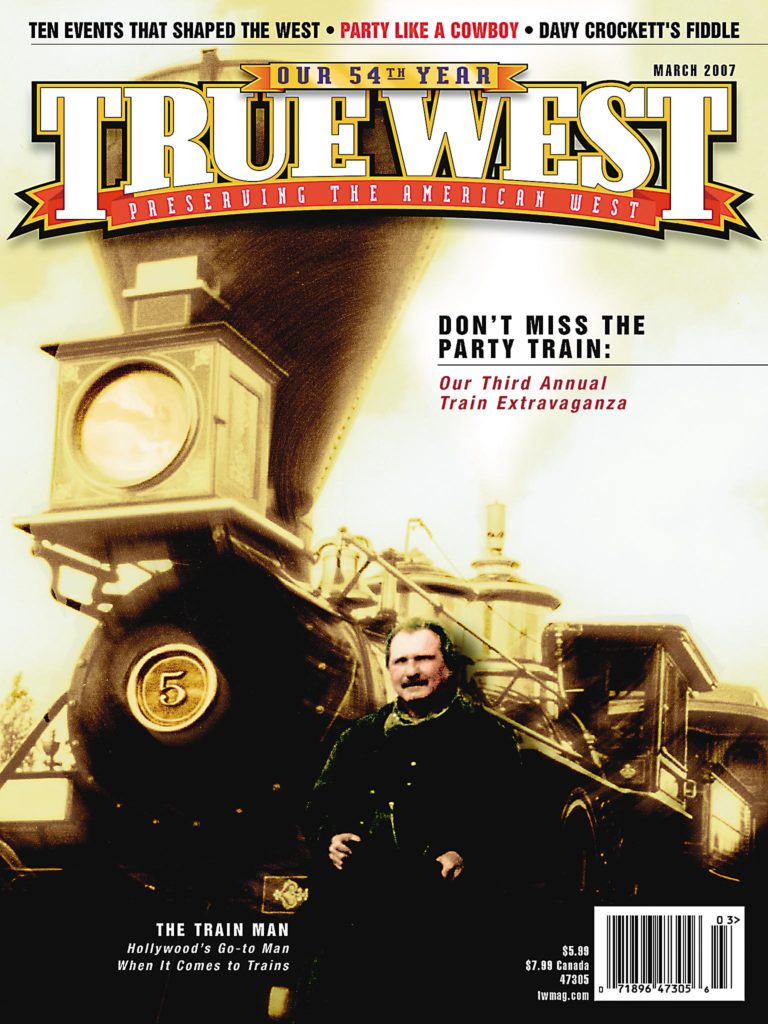

Some of the rolling stock was scrapped, while others were shipped to Hawaii and Alaska, and helped in the WWII effort. Steam Engine No. 5 went to Hollywood, where Wyckoff states it starred in “countless motion pictures”—the most memorable being John Wayne and Marlene Dietrich’s 1942 classic The Spoilers.

In 1962, as part of Nevada City’s Fourth of July celebration, the debut of a musical about the building of the railroad, titled “Never Come, Never Go!,” took place.

In 2003, the Nevada County Historical Society opened the Narrow Gauge Railroad & Transportation Museum (530-470-0902 • ncngrrmuseum.org) at 5 Kidder Court in Nevada City, California. Its star is steam Engine No. 5, an 1875 Baldwin.

This rail line holds the distinction of a rich and prosperous 12 years under the leadership of a stellar businesswoman. And the good folks at the Narrow Gauge Railroad & Transportation Museum aren’t going to let people forget her. Just last year, they dedicated a reconstructed rail bus to her. Right now the railbus takes visitors through the museum rail yard, but hopefully soon it will include longer excursions on narrow gauge lines throughout the West.