When freelance producer Luis Barreto presented his idea for a hands-on history PBS series to Craig Carter, the cowboy-wrangler told Barreto he was out of his mind. Texas Ranch House, Carter said, was a stupid idea.

When freelance producer Luis Barreto presented his idea for a hands-on history PBS series to Craig Carter, the cowboy-wrangler told Barreto he was out of his mind. Texas Ranch House, Carter said, was a stupid idea.

“He told me, ‘This is never going to work. You don’t have enough time to train these people. You guys are nutty if you think this is easy work,’” Barreto recalls. “Then the guy holds up his hand and his thumb’s missing, and he tells me, ‘I did this when I had 10 years’ experience.’ Of course, I’m trying to keep a poker face, but inside I’m like: God, what am I getting into?”

Turns out, what Barreto, Carter, crew and 15 ordinary 21st-century folks got into was a once-in-a-lifetime chance to go back to 1867 Texas and play cowboy, PBS-style. When the show wrapped, there were no missing digits (or any bad injuries) and some pretty good drama where Reality TV meets American history.

Texas Ranch House, which premieres May 1-4, is the brainchild of Thirteen/WNET New York and Wall to Wall Television, producers of two other critically acclaimed hands-on history programs, Frontier House and Colonial House. But, Barreto says, Texas Ranch House is, hands-down, the most demanding show of the bunch.

“The other programs dealt with livestock in very minimal ways,” he says. “We had 200 head of longhorn, 25 head of horses, various pigs and goats, 15 participants and a crew of 45-55 people to deal with. All that on a 400-square mile ranch in the middle of nowhere.”

Eventually, Barreto’s biggest problem came in the editing room. “We probably have enough material to do two seasons, but I only have one eight-hour season,” he says.

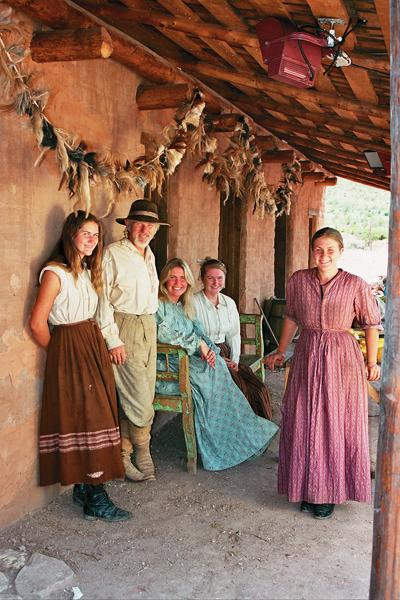

Filmed in West Texas, often with temperatures above 100 degrees, Texas Ranch House beams modern time travelers into post-Civil War Texas. The Cookes (a family of five from California) work to get their ranch off and running, assisted by a 25-year-old servant from Washington, D.C., and several hired hands: a 52-year-old Puerto Rican native now living in New York; a 35-year-old USDA cattle inspector; a 56-year-old retired colonel; a 20-year-old Vermont native; a 22-year-old Englishman; a 22-year-old Arizonian; a 30-year-old Texan; a 31-year-old physical education teacher/coach from Colorado; and Anders Heintz, a 25-year-old native from Sweden now living in Missouri.

Not exactly the cowboys you’d find in an Owen Wister novel.

“When do you get the chance to go live in an 1867 ranch and actually be in one and see what it feels like?” Barreto says. “To me, it plays to all the baser human instincts that we have about survival. Can we make it? The more complicated life gets, I think the more people want to see and experience what real simple life is all about. That intrigued me enough to want to do it.”

It also intrigued Heintz. “A lot of Americans had American history from when they were born,” the Swedish native says, “and I looked at it as an opportunity to learn American history firsthand. What better way to learn history than actually live it?”

Of course, Heintz had a few advantages over some of his fellow cowboys. As an exchange student in 1997-98, he bunked with a cowboy in Missouri before moving to America in 1999. In Sweden, he rode horses until a bad wreck convinced him that “horses are dangerous.” Once he moved to America, though, he did learn to shoe horses.

Naturally, Heintz was stuck as the farrier in Texas Ranch House. What he wasn’t prepared for, however, was the isolation. “You have about 50,000 acres to play with, but you’re still very limited to that area,” he says, “and you can’t go anywhere…. And the food kinda sucked in the beginning. It was terrible.”

All that cattle, but what did they eat? “Beans,” he says. “Beans, beans and beans.” Lunch on the trail? “Bean burritos, God

love ’em.”

Okay, they had some beef jerky and, eventually, salt pork (“which was heaven”) and bacon. “But it was salted down in barrels,” he says, “and it got old after a while, too.”

As soon as production wrapped, Heintz went off to the Buffalo Rose in Alpine and, if memory serves, ate a steak.

But Heintz does admit he grew accustomed to the basic diet. “It’s amazing how fast you get used to living without all the modern stuff, too. Air-conditioning and stuff? You get used to the heat real quick. Little things like television? Who cares? You don’t need television.”

What Heintz got out of the experience, he says, is “a taste for what [the pioneers] went through.”

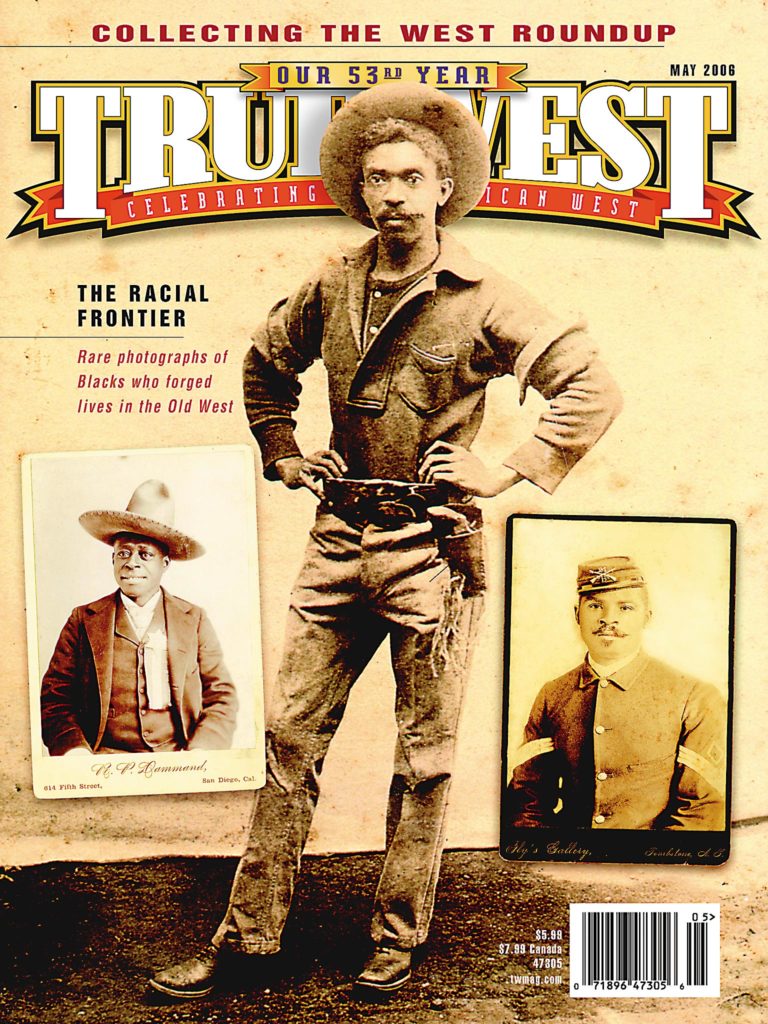

Which, in 1867, was a lot. “The Civil War is just over,” Barreto says. “Reconstruction is getting under way, Texas in particular is being flooded by freed slaves, carpetbaggers, people really looking to start a new life. And with the concentration of maverick cattle in the Texas plains, it was an opportunity for the right forward-thinking man to really step into a place and pick a fortune right off the ground. If he had the wherewithal, and the manpower, he could drive a thousand head of cattle to market and establish himself as a major player in the beef industry. For us, we saw it as a solid historical place to go where many people from many walks of life converged in one place.”

Thanks to the commitment of all participants, Barreto came away pleased with Texas Ranch House. “If I don’t do anything else after this, I’m going to walk away a happy man,” says Barreto, before quickly adding: “Understand, I want to do something else.”

And it turns out, wrangler Craig Carter came away thinking Barreto’s concept wasn’t so crazy after all.

“At the end of the three months,” Barreto recalls, “I asked Craig, ‘Would you hire any of these guys to work on a roundup with you?’ And he said, ‘I’ll take any of them any day of the week.’ To me, that was quite a compliment.”

Johnny D. Boggs has worked enough cattle to know he’d rather eat hamburgers at the Bobcat Bite in Santa Fe, New Mexico, than herd them little dogies.

Photo Gallery

– By Debra Falk/Thirteen/WNET New York –