Why Oklahoma has agreed to do the novel of this aging academic, I do not know,” Willard Wyman wrote the editors and marketing department of the University of Oklahoma Press prior to the release of High Country. “Certainly they know, as I know, that it is risky. But it is about a distinctly Western craft…. And it is not an awkward book.”

Why Oklahoma has agreed to do the novel of this aging academic, I do not know,” Willard Wyman wrote the editors and marketing department of the University of Oklahoma Press prior to the release of High Country. “Certainly they know, as I know, that it is risky. But it is about a distinctly Western craft…. And it is not an awkward book.”

No indeed. High Country might have been written by an “aging academic.” It might have been that man’s first novel, almost his first fiction. But it told in sweeping prose the story of a high country packer and became a story not only of the packer, but also of the high country. And it did so in the same way Norman Maclean’s A River Runs Through It became much more than a book about fishing. It also won the Spur awards from Western Writers of America for both Best First Novel and Best Novel of the West.

“My background—an army child who grew up on cavalry posts, was sent as a boy during WWII to work on a Montana ranch, took a job packing horses in Montana the moment I graduated from college, have packed for 50 years even as I received degrees, taught literature, became a dean and then a headmaster—may be different from Maclean’s in focus, but not in kind,” Wyman wrote. “We both have dirt beneath our fingernails. It’s just that he concentrated on fishing; I concentrated on packing. We both knew horses—as well as books.”

That idea that a writer needs to have dirt beneath the fingernails is more than theory. In the case of book/magazine winners of this year’s Spur awards from Western Writers of America, the dirt comes from years of writing, being on the land, listening to the stories and learning the ways of Western people and places.

The “Dirt”

It is strange writing this story of Spur winners in 2006. As a journalist, I’ve always been disallowed in writing “news” about myself. Yet, here on the Spur Winner’s list is my own book, Chief Joseph: Guardian of the People, published by Forge Books in the “American Heroes” series and selected as the Best Biography of 2006.

I have a bit of dirt under my own fingernails, having earned it by traveling—over a period of years—the Nez Perce Trail across Montana, Yellowstone National Park, Idaho and Oregon. Those nails are short, rough, not at all manicured. I chewed them down to the quick the day I got into a jet boat to travel up the Snake River to Dug Bar, near where Chief Joseph and his people crossed the river as they left their homeland for the last time. I fear rivers and intensely dislike boat rides, but undertook that particular trip “in the name of research.” I much preferred the day I spent in the saddle on the back of a good horse, riding in the rain over Mist Creek Pass in Yellowstone National Park, along the route the Nez Perces had followed.

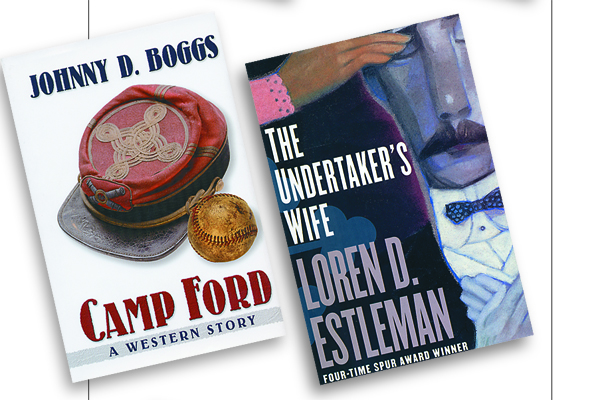

The dirt on Loren D. Estleman is he makes his home in Michigan, where he writes detective stories and top-notch stories of the American West. And yes, I can say that. He has five Spur awards on his office wall to prove that his peers have recognized his storytelling expertise time after time. This year’s Spur came for The Undertaker’s Wife, a Forge novel about a decidedly non-romantic character. It takes a strange, calculating mind to even think of writing a story of Lucy Connable.

But Estleman did not win easily, no indeed. The competition was tough in the Best Western Novel category this year, so tough in fact that there was a tie for the Spur. Johnny D. Boggs of Santa Fe, New Mexico, also deviated from traditional Western storytelling in his winning book from Five Star, Camp Ford, the account of a 19th-century baseball team. It is as much about America’s pastime as it is about the West and is Johnny’s first Spur for a novel, although he already has one at home for his short story, “A Piano at Dead Man’s Crossing,” which he won in 2003. That wasn’t exactly a traditional story either since it was told by the piano.

For his Spur-winning book Dakota (St. Martin’s Press), Matt Braun of Winsted, Connecticut, wrote about Teddy Roosevelt, a man who came from the East and greatly impacted the West, not only in his adopted state of North Dakota and community of Medora, but as president of the United States; ultimately, he established the century-old Antiquities Act that preserved monumental places such as Devil’s Tower. Like Boggs, this is Braun’s second Spur; he won the first in 1976 with his story of an Oklahoma family, The Kinkaids.

Louis S. Warren of Davis, California, won his first Spur for Best Historical Nonfiction with Buffalo Bill’s America: William Cody and The Wild West Show, published by Alfred A. Knopf. This is the first book to fully explain what inspired a buffalo hunter and army scout to become a showman, why his show was a success for so long and why he told the lies he did. Much of Warren’s new findings on Cody stem from the depositions of Cody’s divorce trial housed in the Wyoming State Archives.

David Dorado Romo of La Union, New Mexico, received the Spur for Contemporary Nonfiction with Ringside Seat to a Revolution: An Underground Cultural History of El Paso and Juarez, 1893-1923, published by Cinco Puntos Press. His work brings to light fronterizos, a group of people, not wholly Mexican nor wholly American, who helped launch the Mexican Revolution, people like Pancho Villa, Teresa Urrea (October 2006 TW) and maid Carmelita Torres, whose protest sparked the border Bath Riots in 1917.

Winning her first Spur is Lori Van Pelt (October 2006 TW) of Saratoga, Wyoming, who earned the award for her short story, “Pecker’s Revenge,” in her collection of short stories published by the University of New Mexico Press under the same title. The story chronicles the gold lust of one man who, no matter what comes his way, remains “stuck to his dream.”

The Poetry Spur went to a man who hung out with the major voices in the 1960s—Allen Ginsberg, Charles Olson, Gary Snyder—before he moved to his ranch where Arizona and New Mexico meet at the Mexican border. Drum Hadley of Animas, New Mexico, shared one of his poems from the Spur-winning Voice of the Borderlands as an invocation prior to the Spur Banquet when the awards were presented in June in Cody, Wyoming. His book was published by Rio Nuevo.

Book winners in the categories for young readers included the Storyteller Spur for Klondike Gold, written and illustrated by Alice Provensen, and the Juvenile Fiction Spur for Black Storm Comin’ by Diane Lee Wilson, both published by Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing. Klondike Gold recounts real-life miner Bill Howell’s experiences during the 1897 gold rush on the Yukon. Black Storm Comin’ shares the exploits of the Pony Express through the eyes of 12-year-old Colton Wescott.

A professor of astronomy and anthropology took home the Juvenile Nonfiction award—Anthony Aveni, for The First Americans: The Story of Where They Came From and Who They Became, published by Scholastic Nonfiction. Aveni’s book celebrates these First Americans by highlighting one or two from each region of the country, such as the Anasazi, Kwakiutl and the Taino.

Winning the spur for Short Nonfiction was Paul Hedren of O’Neill, Nebraska, for “The Contradictory Legacies of Buffalo Bill Cody’s First Scalp for Custer,” published by Montana: The Magazine of Western History. Hedren tracks the history of the stories and art celebrating/ignoring Cody scalping Yellow Hair, a Cheyenne warrior, during an 1876 battle near Nebraska’s Warbonnet Creek.

Since 1953, Western Writers of America has promoted and honored the best in Western literature with the annual Spur awards, selected by a panel of judges. Awards are given for works whose inspiration, image and literary excellence best represent the reality and spirit of the American West. Now that the 2006 awards have been presented, it is time to begin thinking about entries for works published this year. Posted at westernwriters.org are rules and entry forms.

For those whose tales are still in the works, remember, it’s far better to write from experience. So don’t be afraid to get some dirt beneath your fingernails before you set out to write the next great Western.