The Dakota Uprising that began in Minnesota on August 17, 1862, quickly grew into the largest “Indian War” in Trans-Mississippi American history. Developing from broken treaties, social and cultural stress, late annuity payments, land hunger, physical hunger, misunderstanding and pride, the conflagration soon encompassed most of the northern and central Great Plains.

The Dakota Uprising that began in Minnesota on August 17, 1862, quickly grew into the largest “Indian War” in Trans-Mississippi American history. Developing from broken treaties, social and cultural stress, late annuity payments, land hunger, physical hunger, misunderstanding and pride, the conflagration soon encompassed most of the northern and central Great Plains.

1. The Dakotas, the eastern branch of the Sioux Nation, were united in their desire to kill white Americans.

False. Of the four bands of Dakotas, only two were more or less resolved to kill or drive away the whites. During the most violent first week of the uprising, about 350 settlers were killed. Dakotas from all four bands took part in rescuing, saving and recovering nearly 400 refugees and captives.

2. Trader Andrew Myrick’s infamous statement, “Let them eat grass,” was the key insult to the Dakotas that caused them to revolt.

False. Only the Indians witnessed Myrick making the “grass” statement. An interpreter’s daughter first mentioned it 57 years after the event. Since then, however, the claim that this incited the Dakotas to revolt has proliferated as truth in virtually every subsequent retelling. Like so much of our history, unfortunately, repetition is equated with accuracy.

3. Because of the Dakotas’ smoldering resentment, secret plans were made to rise up

and drive out the whites at a given signal.

False. The war began because a few warriors accused each other of being cowards, afraid to steal a white farmer’s hen’s eggs. Little Crow, the Mdewakanton leader, did not want war, but he succumbed when he was called a coward. The disastrous affair commenced for little other reason than a few men could not abide being called “chicken”—a malady that still infects many of our statesmen today.

4. Little Crow had planned the war beforehand and was well prepared.

False. Shortly before the conflict, the hungry Little Crow and a few of his men had pawned their three shotguns to a settler for two cows. The chief would not have given away his weapon had he planned on starting a war in three days.

5. Minnesota farmers carried on the tradition of the armed American settler by plowing his field with his rifle near at hand.

False. The settlers had few firearms, and the idea of the frontier settler as a Davy Crockett with trusty “Old Betsy” at hand was mostly a myth. The community where Little Crow pawned his weapons consisted of about 50 people. When Little Crow gave them three shotguns, they now had a total of five—but with only four bullets. Other communities, mostly German or Scandinavian, had just as few weapons.

6. The Dakotas attacked frontier towns.

True. The Dakotas attacked New Ulm on August 19 and 23. The battles resulted in the near destruction of the town and the deaths of about 34 whites, plus about 80 wounded. The only other Indians versus whites battle in which more whites were killed and wounded came with the defeat of Gen. George Custer and the 7th Cavalry at the Little Big Horn in 1876.

7. The Dakotas never attacked frontier forts in the West.

False. The Dakota attacks on Fort Ridgely in Minnesota on August 20 and 22 were close-run struggles. If not for the resolute defenders firing a couple of howitzers, the Dakotas would have taken Fort Ridgely.

8. The Dakota Uprising grew into the Dakota War, the largest of the four Sioux wars.

True. The Dakota War holds the records in a number of categories, the first being in number of casualties. In August 1862, the Dakotas erupted in Minnesota. Over the course of a few months, they killed anywhere between 450 to 800 whites, depending on the source cited. The State of Minnesota records the number of dead at 644, with 23 counties depopulated. King Philip’s War in colonial New England in 1675-76 had about 1,000 white casualties, which occurred over the course of 14 months. When the casualties of the Dakota War through 1864 are totaled, they exceed King Philip’s War.

9. The Dakota War was greater than the “Great Sioux War.”

True. The fourth Sioux War of 1876-77, often called “Great,” was topped by the Dakota War in other respects. The Dakota War had more casualties and numbers engaged. Indian losses in the 1876-77 war were about 200 killed and wounded, while white losses were 408. In the 1862-65 conflict, Indian losses were about 800, while the white losses were 590. In the “Great Sioux War,” the combined columns of Crook, Terry and Gibbon totaled about 2,400 men—a poor second in numbers compared with Sibley and Sully’s 4,500.

In terms of dollars spent, the “Great” War also comes out second. While it cost the taxpayers a little over $2.3 million, the Dakota War cost in excess of $10 million.

10. The Sand Creek “Massacre” of 1864 caused the Indian Wars.

False. The Dakota conflict set the spark in 1862. It spread to the Nakota and Lakota to the west, then south to the Cheyenne and Arapaho. All the tribes of the northern and central plains were at war long before Sand Creek, as were the Comanche and Kiowa tribes on the Southern plains.

Gregory F. Michno, author of Dakota Dawn: The Decisive First Week of the Sioux Uprising, August 17-24, 1862, published by Savas Beatie.

Photo Gallery

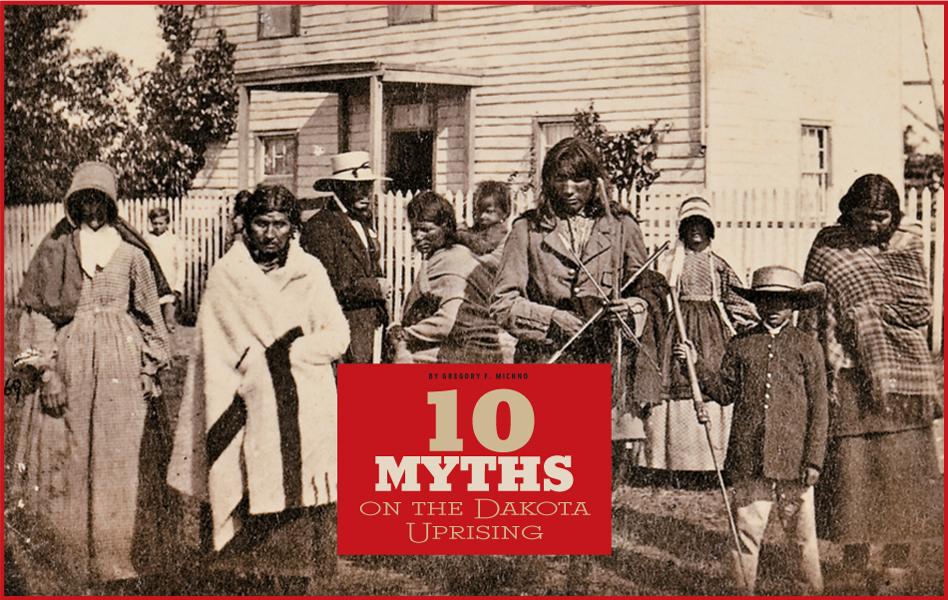

Photojournalist Adrian John Ebell arrived at the Yellow Medicine Agency near Williamson’s mission only three days before the uprising. He photographed these people, escaping from the killings, as they ate dinner on a Minnesota prairie.

This stereoview shows Indians at the mission near Upper Sioux Agency the day before the Dakota Uprising hostilities broke out. Shown with them is Rev. Thomas Williamson, in white hat, along with his wife, Margaret. After surviving the ordeal, Williamson called on President Lincoln to release the Dakota prisoners; by 1866, he had obtained freedom for those prisoners who remained.

– All images True West Archives –

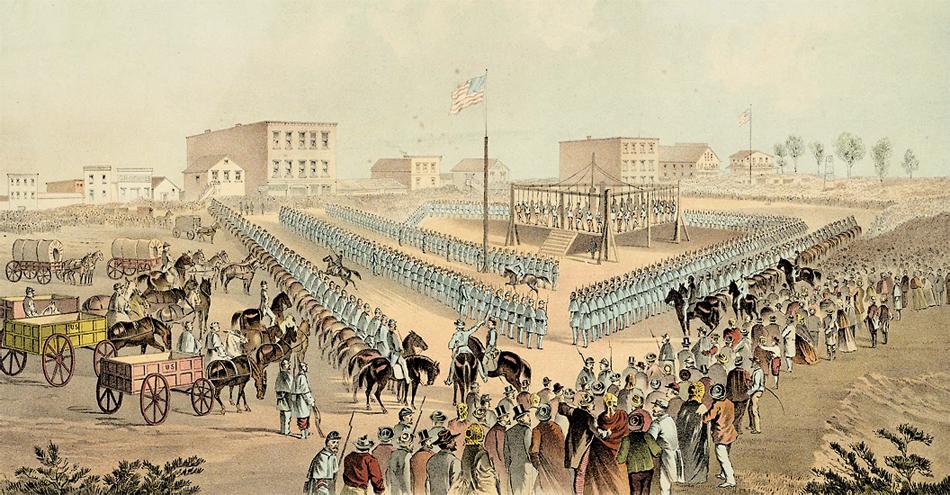

On December 26, 1862, the 38 Dakotas were led to a massive gallows constructed in Mankato. When the platform dropped, a prolonged cheer erupted from the 1,400 soldiers and hundreds of civilians surrounding the square. Ironically, the hangman was William Duley, who believed his wife and children had all been killed; in fact, they had been ransomed and were safe at the Yankton Agency in Dakota Territory.