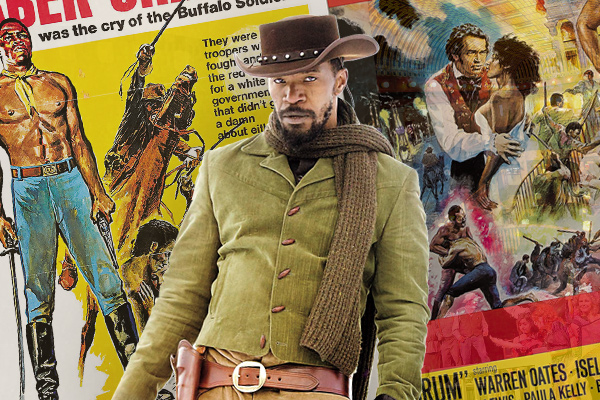

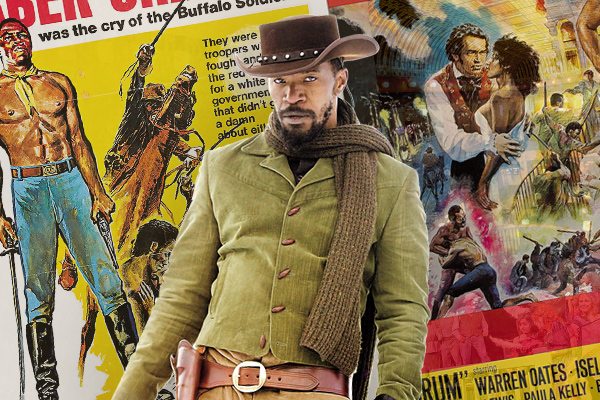

Quentin Tarantino has called his upcoming film Django Unchained a “Southern,” as it takes place in the South, moments before the first shots were fired at Fort Sumter. His story of runaway slave Django (Jamie Foxx)

Quentin Tarantino has called his upcoming film Django Unchained a “Southern,” as it takes place in the South, moments before the first shots were fired at Fort Sumter. His story of runaway slave Django (Jamie Foxx)

has been tied to Spaghetti Westerns as a major influence (certainly the title), but the cinematic roots of Tarantino’s project are more complex than just Euro Westerns, and these deserve to be explored.

Decades before Fred Williamson or football star Jim Brown made their Western debuts, directors Raoul Walsh and John Ford blazed a trail by casting black stars in major roles, which challenged audience expectations of the genre they helped invent.

Released in 1957, Walsh’s Band of Angels remains a bizarre mix of Civil War clichés and frank scenes about race and sex. Sidney Poitier plays the “house servant” who hates his master (Clark Gable) for killing him with kindness. Poitier joins the Union Army and later confronts Gable and his woman (Yvonne De Carlo), a half-caste who he despises for betraying her race.

These raw scenes almost make up for Angels’ embarrassing “Old Massa” moments; but despite its faults, Walsh’s film took a significant step by addressing Poitier’s character’s anger.

While Poitier was becoming a star in modern subjects, a black lead in a major Western was years off. Ironically, John Wayne’s curmudgeonly mentor would be the one to launch a bombshell against the “Western Color Barrier.”

Coming after 1959’s listless The Horse Soldiers, 1960’s Sergeant Rutledge was Ford’s least appreciated masterwork. Anchored by Woody Strode’s superb performance as the Buffalo Soldier wrongly accused of killing a white girl, Rutledge lays bare racial and military hypocrisy.

Ford loved tradition, but he also embraced revolt; if he could upset the apple cart, he would. Rutledge explodes the cart by creating the first black hero in a studio Western; Ford honors the black cavalry while despising its treatment from command.

In 1960 audiences weren’t ready and Rutledge failed, but it became an inspiration for black actors. Strode later said, “You never seen a Negro come off a mountain like John Wayne before. I had the greatest Glory Hallelujah ride across the Pecos River than any black man had on the screen.”

With that ride, Strode led a slow charge of black heroes on horseback: Poitier, playing against type, in 1966’s Duel at Diablo, while Brown fought alongside Stuart Whitman (1964’s Rio Conchos) and Burt Reynolds (1969’s 100 Rifles). Despite his strong presence, Brown was still playing support to the leads, and it would take the success of Shaft in 1971 to put box-office power behind black action stars.

After Shaft, Americans saw black star power in 1971’s Skin Game, as fake slave Lou Gossett (better known as Louis Gossett Jr.) and conman James Garner outfoxed would-be masters out of their cash. Poitier directed 1972’s Buck and the Preacher and starred in it as a trail guide leading freed slaves west in a blend of action, conscience and sly comedy.

These films weren’t gritty enough for the crowd cheering on 1972’s Super Fly; the Blaxploitation Western had to follow a different path than Wayne’s or Clint Eastwood’s. The loner who took on outlaws was now an ex-slave who revenged himself against injustice, while bedding the white heroine between bloody gunfights.

Fred Williamson became king of the new genre, starring in 1972’s The Legend of Nigger Charley, 1973’s The Soul of Nigger Charley, 1975’s Take a Hard Ride and Boss Nigger, and 1976’s Joshua and Adios Amigo.

Payback for slavery was often a motivation in these films, as Williamson and other black Westerners went from being smart alecks who humiliated their white antagonists to justifiably gunning them down.

The Legend of Nigger Charley is Williamson’s most successful Western vehicle. Its story of three runaway slaves who can never break the chains of their past has pathos beyond the shoot-outs. Technically raw, but with good performances, Charley was a smash, and its success prompted Ford to begin work on a project about the first black graduate of West Point. Ford wanted Williamson to star, but he died before the director could complete the journey he’d begun with Sergeant Rutledge.

By 1975, the Blaxploitation market was waning, and the form was going through more changes, reflected most notoriously in that year’s Mandingo. Stunningly photographed, Mandingo takes the pretentious stance that its story of rape, torture and miscegenation on the plantation was a “true” picture of the pre-Civil War South, but the plot is actually exploitation on a grand scale.

Mandingo depicts the hideousness of slavery in an unusually frank and open way, but the film’s seediness almost destroys any legitimate message it might have had. Reviled by critics for sweaty sex, castrations and the finale where Mandingo is boiled and pitch forked, the film remains one of the great examples of studio-produced trash.

Of course, it was a hit.

The 1976 film Drum was the cheap follow-up. Steeped in sex and bloodier slave violence, Drum has no pretentions about itself and holds nothing back, which might be the ultimate strength of the Blaxploitation Western.

Seen simply as product, filmmakers were left on their own as long as there were enough gunfights and naked saloon girls on screen. With that freedom, their stories could deal with tough subjects in a way larger films, with more to lose, could not.

When Ford failed with Sergeant Rutledge in 1960, more than 10 years passed before a Black Western once again became viable with moviegoers. The Black Westerns’ time was brief, but these films have left a legacy and influence that is still being felt with the anticipated Christmas Day release of Django Unchained.

C. Courtney Joyner is a screenwriter and director with more than 25 produced movies to his credit. He is the author of The Westerners: Interviews with Actors, Directors and Writers. Film journalist Justin Humphreys is the author of Names You Never Remember, With Faces You Never Forget.