In 1886, Solomon Butcher had his eureka moment, the biggest idea of his life.

In 1886, Solomon Butcher had his eureka moment, the biggest idea of his life.

He would compile a book, a photographic history of the pioneers of Nebraska’s Custer County.

Butcher had moved to the county, named after the U.S. Army officer George Armstrong Custer, in 1880, leaving Illinois behind in order to claim some of the government land being given away as part of the 1862 Homestead Act.

Along with pictures, he would include in the book his neighbors’ biographies and recollections. He called the plan his “history scheme.”

The same year that he thought of his history scheme, the Burlington and Missouri River Railroad came to Broken Bow, the county seat, for the first time. Every day, the train brought in more people and goods from the outside world. The era of sod houses in the wilderness was disappearing fast, and Butcher wanted to tell its story while there was still time.

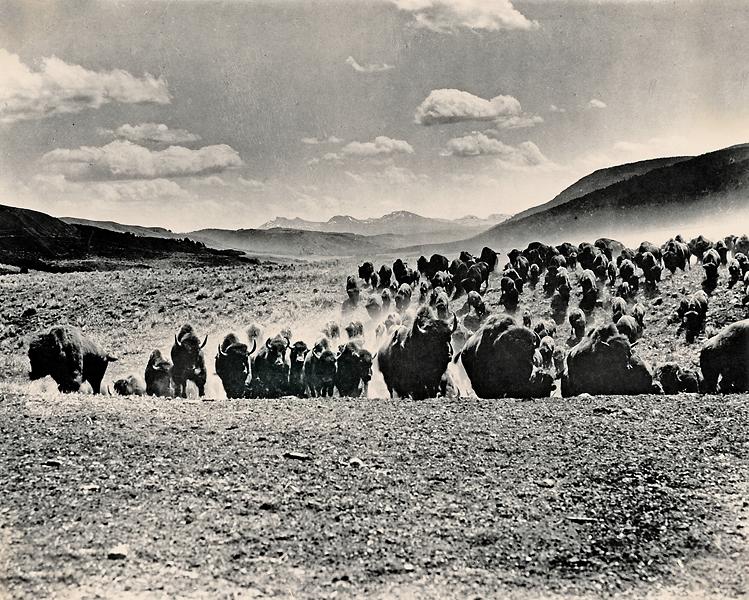

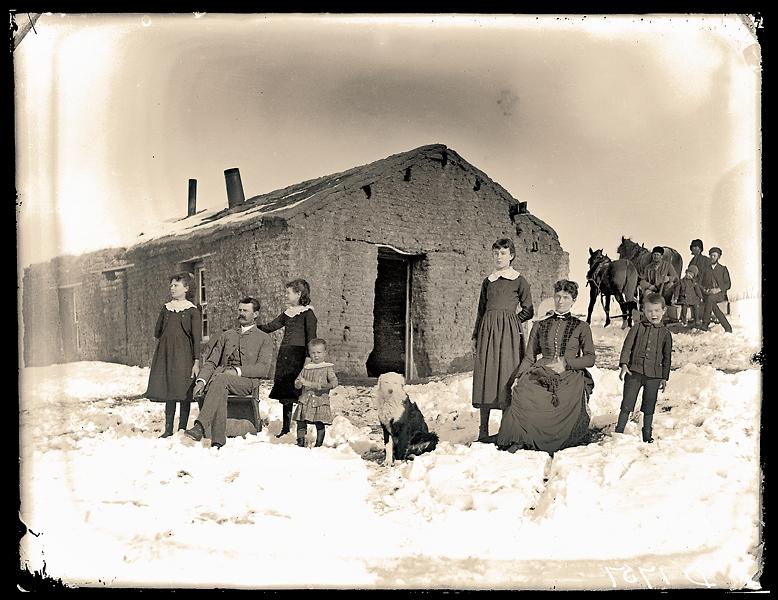

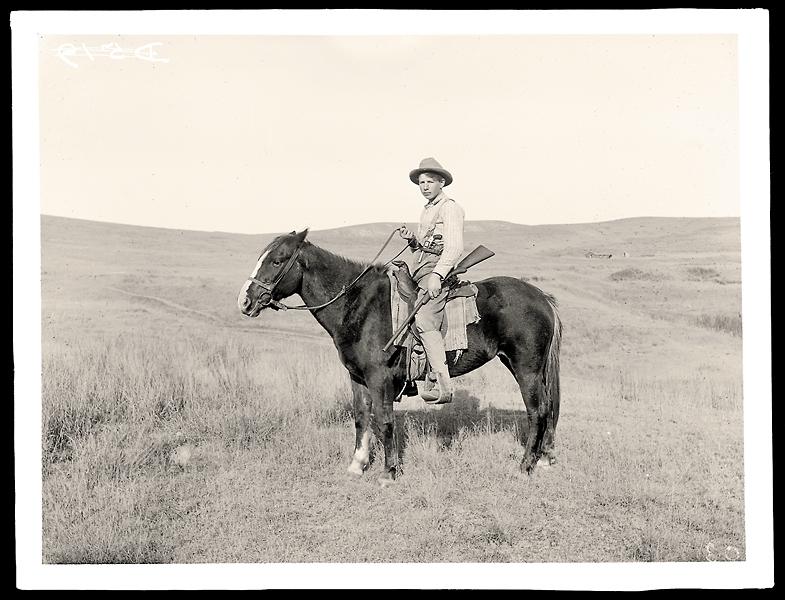

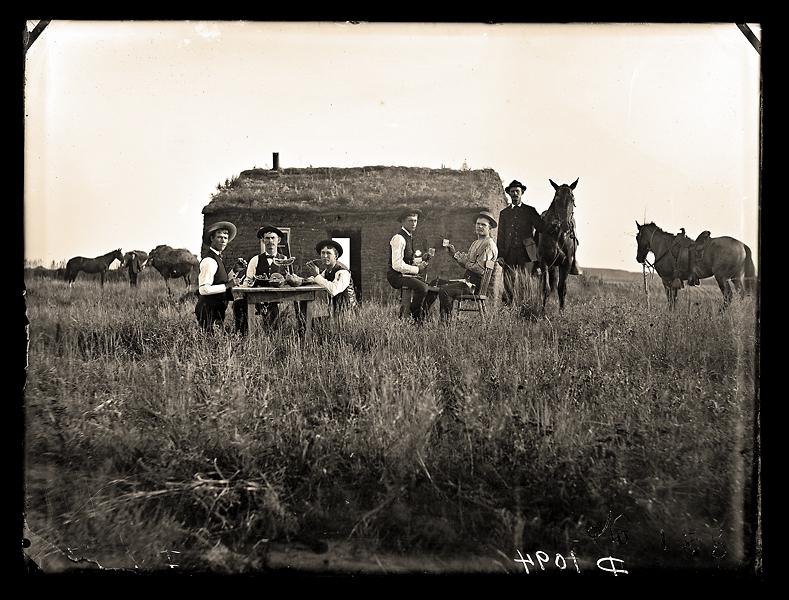

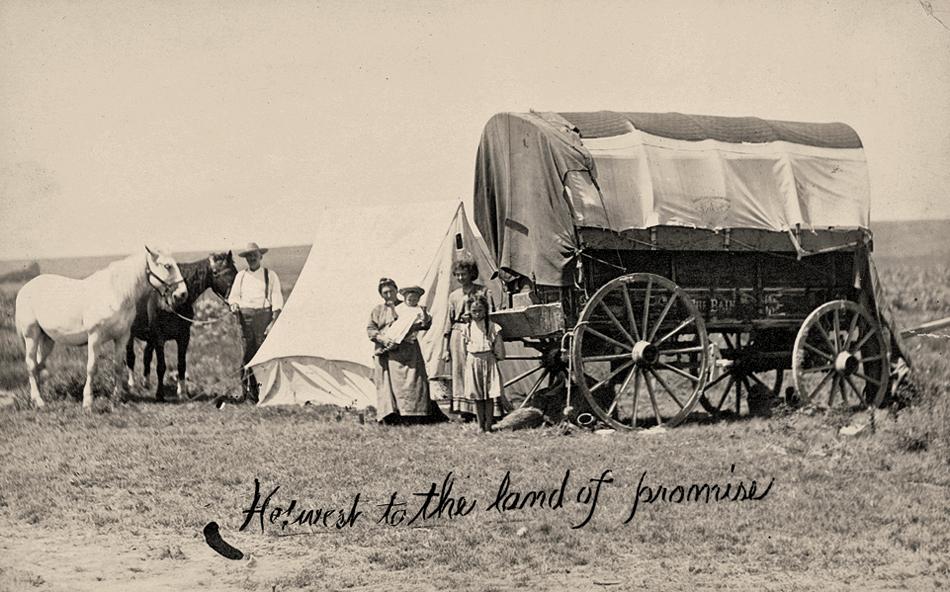

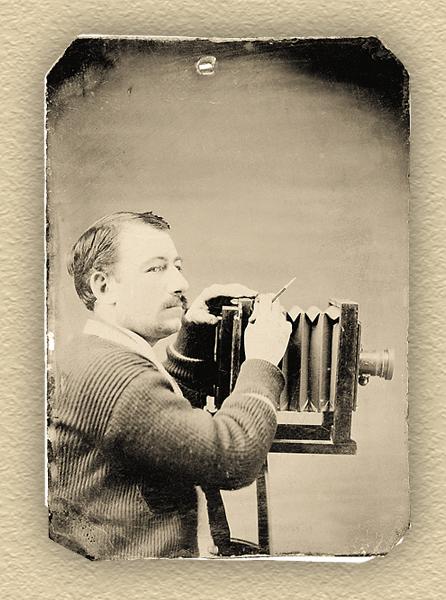

With his camera and portable darkroom stowed in the back of a horse-drawn wagon, Solomon began to roam. In the clear prairie light, he posed the people of Custer County with the things that were important to them. In his photographs, farm families stand in their fields or in front of their soddies, flanked by their household possessions, their horses and usually a dog or two. Ranchers are pictured on horseback with their cattle or flocks of sheep. His subjects were everyone and everything that was part of life on the plains. And always, behind Solomon’s people is the wide land itself, reaching far into the distance.

“Some called me a fool, others a crank, but I was too much interested in my work to pay any attention to such people,” he wrote.

On his quest to photograph the pioneers, Butcher would visit more than a dozen Nebraska counties and even other states. But he concentrated mostly on Custer County, his home. The scenes that he recorded there represent well the larger pioneer experience. Life throughout Nebraska and on the plains of Kansas and the Dakotas was very much the same.

In Nebraska about half of the homesteaders who claimed land gave up at some point and moved away. Those who stayed were stronger, in their way, than prairie fires or blizzards or despair. “There may be better people somewhere in the world, but I have never met them,” wrote one Nebraskan.

The pioneers helped each other; their survival often depended on it. If one man had a well, he shared his water. If weather or illness left a family hungry, neighbors brought food and helped with the crops. Strangers could count on shelter in a storm, and any traveler stopping at a little soddy would receive a welcome and a meal. Even if the house were empty, there might still be dinner. “Help yourself, but for God’s sake SHUT THE DOOR,” read a sign on a Custer County dugout.

By 1892 Solomon Butcher had toured the Nebraska prairie for six years. He had taken 1,500 photographs and collected the same number of stories, one for each picture. He was close to realizing his dream of a book on pioneer history. Then drought settled on the land like a heavy blanket. From 1892 to 1899, Butcher sold no pictures at all.

By 1899, his fortunes had improved. Higher crop prices allowed him to move his family into a new frame home. Then a breakfast fire burned down that new home. Almost everything the Butchers owned was lost, including hundreds of photographic prints and all 1,500 of Solomon’s pioneer biographies. The 1,500 glass plate negatives, however, had been stored separately in a grain shed.

He was 43 when his house burned down, and even though he was broke—again—he quickly resumed work on the pioneer history. As Lynn Butcher later wrote, “My father had what he called ‘Western push and energy’ and there was never any question [about] starting all over again.”

Solomon’s “Western push” drove him to reach his goal. Just 18 months after the fire, he had gathered another batch of stories for his book and selected the photographs to illustrate it. Fifteen years after he had first thought of it, his history project was finally finished. Pioneer History of Custer County, and Short Sketches of Early Days in Nebraska was published in 1901. In a chapter about his own adventures, he wrote, “After fifteen years of such a checkered career as few men have experienced, I have still been able to wrench success from defeat…. How well I have succeeded I will leave the reader to judge after he has read this book to the last page and looked at the last picture.”

The first edition of Pioneer History—1,000 copies—sold out right away. Butcher and his patron, Uncle Swain Finch, immediately ordered a second printing. Pioneer History had sold so well that they planned two more such books, one each for the pioneers of neighboring Dawson and Buffalo Counties. Once again, Solomon hitched up his wagon and took his camera on a ramble—through Nebraska, Wyoming, Utah, Colorado and more. He mailed his glass negatives home, where his family developed them into prints and also into postcards, ultimately producing about 2.5 million postcards of towns and scenery throughout the Great Plains.

Tired of carting the thousands of glass plate negatives with his family on all their moves, Butcher offered up the collection for sale in the hopes they would be preserved for history. He sold his collection to the Nebraska State Historical Society for $600 in 1913.

The history-loving photographer died at the age of 71, in 1927, believing that he had failed, that few would ever value his life’s work. He was wrong. Butcher had seen the wild grasslands of America being transformed into farms and towns, and he had been passionate about documenting the pioneer days before they vanished forever. He succeeded. Solomon’s photograph collection—more than 3,000 extraordinary images in all—forms the most complete record of the sod house era ever made.

Nancy Plain is the author of Light on the Prairie: Solomon D. Butcher, Photographer of Nebraska’s Pioneer Days, published by the University of Nebraska Press. She has also won two Spur awards, for Sagebrush and Paintbrush: The Story of Charlie Russell, the Cowboy Artist, and for With One Sky Above Us: The Story of Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce Indians.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Nebraska State Historical Society ID. 12615 –

– Courtesy Nebraska State Historical Society RG. 3211 –

– Courtesy Nebraska State Historical Society ID. 11234 –

– Courtesy Nebraska State Historical Society ID. 12637 –

– Courtesy Nebraska State Historical Society ID. 10349 –

– Courtesy Nebraska State Historical Society ID. 12715 –

– Courtesy Nebraska State Historical Society RG. 3371 –

– Courtesy Nebraska State Historical Society ID. 10236 –

– Courtesy Nebraska State Historical Society ID. 16311 –

– Courtesy Nebraska State Historical Society ID. 14394 –