Everybody wants to make a Western. It’s a fact. Few directors of note, if you were to ask them, would say, “I’m not interested in Westerns; I have my heart set on another slasher movie or romantic comedy.”

Everybody wants to make a Western. It’s a fact. Few directors of note, if you were to ask them, would say, “I’m not interested in Westerns; I have my heart set on another slasher movie or romantic comedy.”

What holds them back is the idea that Westerns don’t do well at the box office. Yet Westerns are one of those toy chests everybody wants to open. Actors, directors, writers—males for the most part—all want to play with the figures inside the box.

The Western formulas are, to the naked eye, pretty simple. The truth is, good Westerns are extremely rare and hard to make, which is why it makes sense that James Mangold has been wanting to remake 3:10 to Yuma for years.

It’s got everything: action, tension, interesting characters and gunplay. Elmore Leonard, who wrote the original story, didn’t waste words. This is not a Western that requires much historical background. It features a bad guy, a good guy, a hotel room and a passel of villains in the street below.

The story is what I think of as a “siege” Western. Like High Noon, Hombre (which Leonard also wrote) and Rio Bravo, it locks a handful of characters in a box and then shakes the box to see what kind of rattle they make.

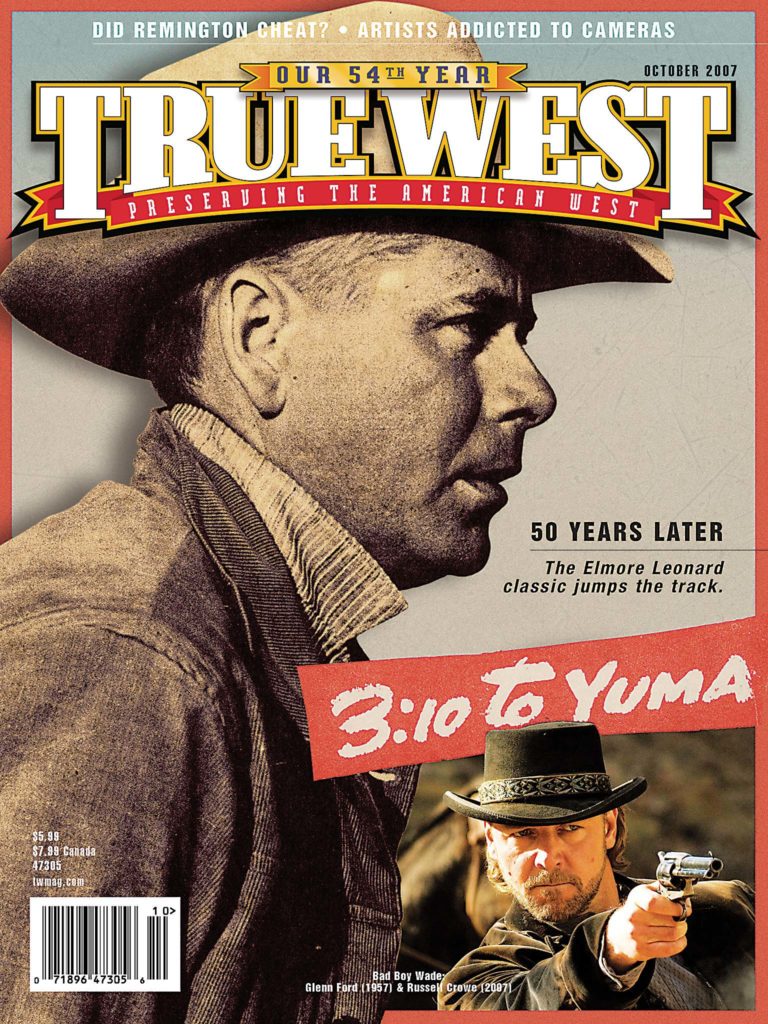

When director Delmer Daves turned Leonard’s story into a movie in 1957, he and the writers made a few modifications. The good guy deputy who is simply doing his job, was changed into a failing rancher with a family he can’t feed. Dan Evans (Van Heflin, echoing his character from Shane) just happens to be on the spot when he sees a gang of bandits rob a stage and kill a man.

Soon after, he stumbles into an opportunity to make some money by assuming the job of guarding the captured leader of the gang, Ben Wade (Glenn Ford). All he has to do is make sure he gets his prisoner on the 3:10 train that will carry Wade to Yuma, and to the territorial prison.

Wade, who was named Jim Kidd in the story, started out as just a bit player in the gang. Movies don’t work that way, so Wade was turned into a notorious, charismatic outlaw. Ford made the character sing—he had the movie pretty much to himself.

In the new version, Wade, as played by Russell Crowe, is taken even higher. He’s a fancy dressing, philosophically agile figure who makes sketches of birds and women’s backsides, and he has crucifixes on his gun grips. Wade is a couple of moral twists away from being one of those good natured cowboy Robin Hoods who roamed the West in old serials. He’s nearly dashing.

“[I] probably based pretty much every decision about the character from a scene where he discusses the time and the reasons why he once read the Bible from cover to cover,” says Crowe. “That to me is sort of like the central core of who Ben is. And, you know, it wasn’t a very pleasant experience for him. I kind of took the attitude that he doesn’t believe in a benevolent God, that he got stuck somewhere in the Old Testament, you know, and hasn’t come out of there yet.”

Dan Evans (Christian Bale) has gone through some modifications as well. He isn’t just a timid rancher who has fallen on hard times. Now he’s a maimed Civil War vet at the mercy of a bunch of Old West cutthroats who refuse to let their water pass through his land unless he can come up with some money. As in the first film, he watches Wade and his boys go to work on the stage and do some killing.

“He’s pretty much the only person in the story who doesn’t really give a damn about who Wade is,” Bale says. “For him, he’s got to deal with the kind of loan sharks that are ruining his livelihood and destroying his family.”

Dan also has to deal with having an angry son who sees his father as a failure, and who starts to admire Wade. This discord becomes a major theme in the new film that was, at best, only hinted at in the earlier one.

“We wanted to put the boy in the middle,” co-screenwriter Michael Brandt says. “It’s kind of like a little battle for his soul.”

“For me, this movie was all about the son … once we seized upon the idea that it was easy for the son to consider his father almost a loser,” Bale says. “Their life wasn’t going anywhere and here comes this well known gunslinger who’s really charismatic. And you see the son being pulled over to his side. To me, that was ‘movie.’ Then you put those guys on the road, and the theme is really about what’s right and wrong in the world. It really kind of has nothing to do with the Old West.

“Dan is really an idealist, and he does not want to be corrupted by a corrupt society. Trouble is, it ain’t working, you know? His children are turning away, he’s in danger, his ranch is dying.

“Ben Wade, Russell’s character, on the other hand, he’s got a more cynical approach, but he’s very honest and he’s very seductive and charming in that fashion. And despite the fact that this man is a killer, Dan realizes he’s the only honest person in Dan’s life other than his family.

“And I think that’s the main thing, that you can’t actually disagree with what Ben Wade says because he never lies. He says, ‘I’m a thief. I’m a murderer. That’s what I do.’ It’s this perverse thing where this apparent demon, Ben Wade, actually ends up being, in a bizarre way, a kind of guardian angel for Dan,” Bale says.

Director James Mangold was determined to give the Ben Wade character a greater luminosity. “Wade has a kind of a nobility. For example, we see that he doesn’t kill Dan Evans when he knows that Evans is an eyewitness to the robbery and the murder at the beginning.

“And you have to see that pretty much everyone Wade kills is a scumbag to begin with,” he says. “There’s something both brutal, Nietzschean and kind of fair about him, and I think that he’s fascinating for an audience because Russell makes him reviling and admirable at the same time.”

I mention to Mangold that one could say the same for Glenn Ford in the original.

“Absolutely. But the key to making this work is to make sure that the killing he does seems at least arguably justified.”

Mangold also reached farther into the Western toybox to bring out a few Apaches for a brief skirmish, and to shoot a scene that takes place at a railroad construction site, complete with vicious overseers and Chinese workers.

“One of the things I wanted to make clearer in this version is the relationship of the territory to the railroad and the idea that the railroad’s expansion was changing things there,” Mangold says. “I wanted to make a little of the idea that Bisbee, Arizona, the starting point in the story, was a pre-railroad town, and Contention, their destination, was a post-railroad town. And that as you follow the line of construction going toward Contention, it’s a journey into the heart of darkness, toward the flipside, the downside, of the promises and the economic boom the railroad represents.

“I wanted to show that this progress also brings a kind of depravity, including slave labor. That the train represents a move toward civilization, but also a descent into something less pure than the wilderness from which Dan and the audience started. It begs the question, Which is more civilized: corporate corruption or Ben Wade’s kind of corruption?

“And it’s Ben Wade’s point because I thought this story, and I do look at it as a kind of timeless text, only works to the degree that the audience is torn between both points of view, Dan’s and Ben’s. In order to do that, you have to, in a way, subscribe to Ben’s sort of libertarian feelings about what’s happening to the country, and his righteously, rightfully sneering attitude toward the railroad men and the culture that’s coming.”

Mangold is the first one to admit that creating a sympathetic bad guy is far more exciting than creating a good guy.

“One of the great attributes of 20th- to 21st-century literature is the more passive hero. Heroes aren’t Beowulf very often anymore; they’re usually a kind of regular guy, in a jam, who has to evolve. So one of the things you’re faced with in modern storytelling, you better have a f—— active villain if you’re going to have a passive or reactive hero. And there’s so much more fun to building a charming villain, whether you’re talking Hannibal Lecter or Ben Wade.

“There are a lot of people who think of the Western as a genre that works because the stories are simple and the villains wear black hats while the heroes wear white. It couldn’t be more the opposite. I see the black hat/white hat so much more in the Spider-man-type films with the drooling villains who want to blow up the world. It never exists in the Western. You’re sympathethic and curious about every side. Even in some of the most extreme examples, like Shane, Jack Palance has his reasons. He’s not evil because it’s somehow fun to be evil. There isn’t this sophomoric depiction of evil; there are just agendas that do not meet.

“There is no genre more underestimated in its complexity than the Western,” Mangold says. “Over and over again, they’re incredibly, profoundly deep films. Maybe people think about Westerns that way because Tom Mix or the Lone Ranger or Gene Autry, some of the more naïve or friendlier ’50s television versions of the West, were reduced to buffed up good guys versus sniveling bad guys. But on the feature level, it’s so rarely part of what the better Westerns are about.”

As of press date, Lionsgate has moved up the 3:10 to Yuma release date from October 5 to September 7.

Leonard’s Take

“3:10 to Yuma” was born early in the career of writer Elmore Leonard, in 1953, when he was trying to make a living selling stories instead of writing ad copy for Chevrolets.

Today we think of Leonard as one of the most successful novelists of our time. He’s become the front man for a crew of entertaining crime writers who find ways to be funny without loosening their grips on the people and events in their stories.

“I don’t try to be funny, “ he says, “I just try to be real.” And that’s why it works.

We’ve seen great films based on his books: Get Shorty, Quentin Tarantino’s Jackie Brown, Hombre starring Paul Newman and Out of Sight with Jennifer Lopez and George Clooney, which may be the best picture either of them has made. (Leonard’s new novel, in progress, will bring Clooney’s character Jack Foley back into play. He’s calling it Foley’s Back, but he wants to find a better title.)

When Leonard was starting out in the early 1950s, the drugstores and newsstands were loaded with magazines and pulps, and short stories were the currency of the day. It’s difficult to imagine, since short stories today are strictly niche market material. But at the time, a writer like Leonard could receive two cents a word for a tale of a cowboy or a crime. At 81, Leonard still remembers vividly how a 5,000-word story would put $100 in his hands.

“They paid me $90 for “3:10 to Yuma.” I sold it to Dime Westerns in ’53, and it was 4,500 words,” says Leonard, from his home outside Detroit. “And that particular story’s been picked up a number of times for anthologies, and I don’t think it ever made more than 100 bucks each time.”

“3:10 to Yuma” was a smart, lean short story about an underpaid lawman under siege. All the good guy has to do is get the bad guy past his gang of thieves and onto the train to a Yuma prison. Most of the story takes place in a hotel room, where the two sit, counting the minutes.

What complicates matters, and what makes the story good, is that the lawman also has to endure the taunts and temptations the bad guy throws his way. “You know, you really earn your hundred and a half [a month],” the bad guy remarks. The deputy silently agrees.

The story made a solid picture in 1957, when Delmer Daves turned it into a black-and-white feature starring Glenn Ford as Ben Wade—the bad guy—and Van Heflin as Dan Evans.

Leonard tells me Walter Winchell, radio’s godfather of gossip, called the movie “three hours and 10 minutes past High Noon.” By that comment, Winchell probably meant that the original film, like its famous older cousin, had a sustained tension, and that both movies shared a similar story line about a single man alone against great odds.

The new version of 3:10 to Yuma, which stars Russell Crowe as Wade and Christian Bale as Evans, is much more a remake—one could say an elaboration—on the earlier film than it is an adaptation of the original story, which means that Leonard is at least twice removed.

The biggest difference between Leonard’s story and both film versions is that Evans is not a peace officer but a rancher whose family and finances are suffering the effects of a long drought. When he’s offered good money to see that Wade is taken to the train, he accepts.

What’s funny is that Leonard had completely forgotten that his original character was an officer, rather than a civilian. “Oh that’s right, you’re right, he’s a deputy. Oh yeah—Damn! I forgot about that! He’s doin’ his job! He’s gotta do his job.

“When the first movie was made, I remember I thought it cluttered it up to give him the wife and family, and show that he needed the money. I forgot all about that. That gave him his motivation.”

Leonard is pretty acidic when it comes to Hollywood. “They’re always doin’ that—what’s his motivation? They’re always asking you. And I say, ‘Well, he’s a bad guy. That’s his motivation. He’s just baaaad.’ [He laughs.] Not why he’s bad. Who cares? Who knows? ’Cause then you have to stop the movie and explain why he became bad, which is ridiculous. The audience doesn’t give a s—. They want to see some action. Let’s see the guy perform. C’mon!

“So when Glenn Ford at the end pushes Van Heflin onto the train, you know, at the end, and says, ‘I’ve escaped from Yuma before’—Awww Christ! To me, that’s just a cop out.”

This is not a spoiler, by the way, because the new version has a few twists of its own.

“Glenn Ford, he turned down the picture when he thought he was going to be the good guy,” Leonard recalls. “And they said, ‘No, no, you’re the bad guy.’ ‘Oh! Good!’ But he couldn’t be bad all the way, you know. In the end, he had to redeem himself, redeem the character.”

For Leonard, 1957 was a banner year as he saw two of his Western stories made into top quality movies. Even better than 3:10 to Yuma was the adaptation of his story, “The Captives,” which became The Tall T, starring Randolph Scott and Richard Boone, and directed by Budd Boetticher. No one knew it at the time, but the handful of films that Boetticher shot with Scott in the 1950s are today considered to be among the finest Westerns ever made.

“It’s funny because when they showed The Tall T to the press, I was invited, and they were all talking through the picture and saying what was going to happen next.” Leonard says. “And then there’s the scene where Skip Homeier is lured into that cave with Maureen O’Sullivan, and the guys in the screening room were saying, ‘Okay, here’s where we get the fight. Now they’re going to have the big fight.’

“And no. Scott shoves the shotgun under his chin and BANG! And the screen goes red. And they shut up. From then on, they all shut up.”

“I didn’t know Budd Boetticher, I didn’t know what was significant about him at that time,” Leonard says, “but I thought it was great because Richard Boone, he recited his lines exactly the way I heard them when I was writing the story. And then when I wrote Hombre, I sent him, through his agent, a copy of the book. I said ‘You ought to be in this because one of the guys in this is you.’ I never heard a word, but then he did appear in the movie, in the role.”

When Leonard went to preview the new 3:10 to Yuma, the experience was a bit different from watching The Tall T. He was given a sheet with 10 questions the publicists wanted to ask him after he watched the movie.

“And one [question] said, in the ’50s, Westerns became more serious, about the individuals, the characters,” Leonard says, “and then they mentioned The Searchers and James Stewart’s Westerns. And I said I thought The Searchers was the most overrated Western ever made! All it was, was scenery and bad actors. The acting was awful, and nothing happened in it.

“I think one of the best Westerns I’ve seen lately is the one with Kevin Costner and Robert Duvall, Open Range. That gunfight went on forever, and it was good all the way. All those real loud guns.

“I thought one of the best I ever saw was My Darling Clementine with Henry Fonda as Wyatt Earp…. I thought the dialogue was good, the gunfight, of course, at the O.K. Corral, good cast. And I liked Red River a lot—that was a real Western with cattle in it. Not many had cattle, you know. And I remember Apache with Burt Lancaster, who did Valdez is Coming, and Newman did Hombre. The Treasure of the Sierra Madre was a great one.”

Leonard actually wanted to write the script for Valdez is Coming, but he couldn’t convince the producer to hire him to do it. He did write a few screenplays, to earn money so he could write his books. His Western scripts include the made-for-TV Desperado features and 1972’s Joe Kidd, starring Clint Eastwood.

“Joe Kidd I didn’t think was a good movie at all. It had maybe a few moments that were alright. But Eastwood wanted me to, well after Joe Kidd, before it came out, he called me up and said, ‘Do you have something else? I don’t own Dirty Harry and I want to own my next one.’ And that night I got the idea for Mr. Majestyk, so I called him the next day. And he said, ‘That sounds good, write it up.’ It was like a 25-page outline that I wrote. And shortly after I was out in Hollywood and went to see him, and he was ready, he wanted to do it. But then my agent called him up and said, ‘Make up your mind, will you? You got about a week.’ And in the meantime, he found High Plains Drifter, and that’s what he wanted to do, and he did that instead.”

So when is Leonard going to write another Western? “People ask me all the time, ‘Will I ever write another Western?’ I say, ‘I don’t know. If they pay enough, I suppose I will.’”

TWMag.com: Read about Hombre in the extended Elmore Leonard interview.