“You gonna pull those pistols or whistle ‘Dixie?’”

“You gonna pull those pistols or whistle ‘Dixie?’”

Clint Eastwood’s gunslinger famously brushed off a group of Union soldiers with those sneering words—just before he shot all four of them dead. The line was more than a bit reminiscent of the oft-misquoted line Eastwood said in the 1971 movie that catapulted him to fame: “You’ve got to ask yourself one question: ‘Do I feel lucky?’ Well, do ya, punk?,” his Dirty Harry character asked the bad guy at the mercy of his Smith & Wesson Model 29 .44 Magnum.

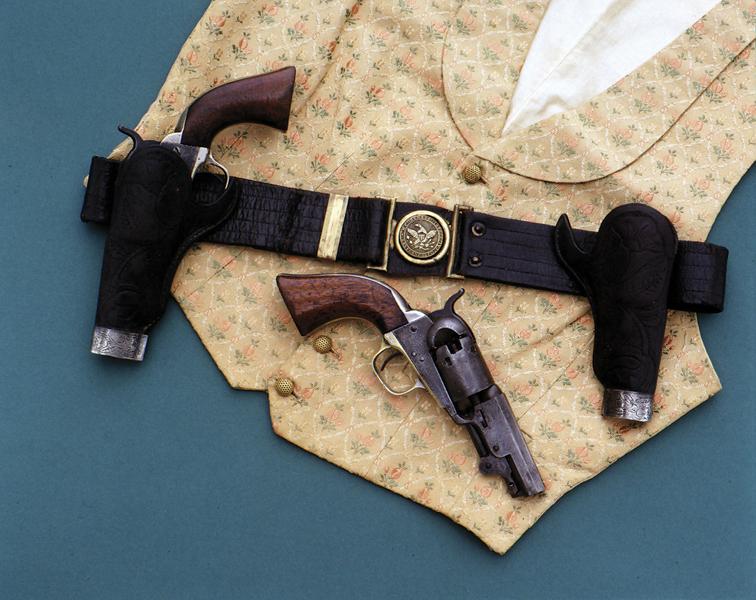

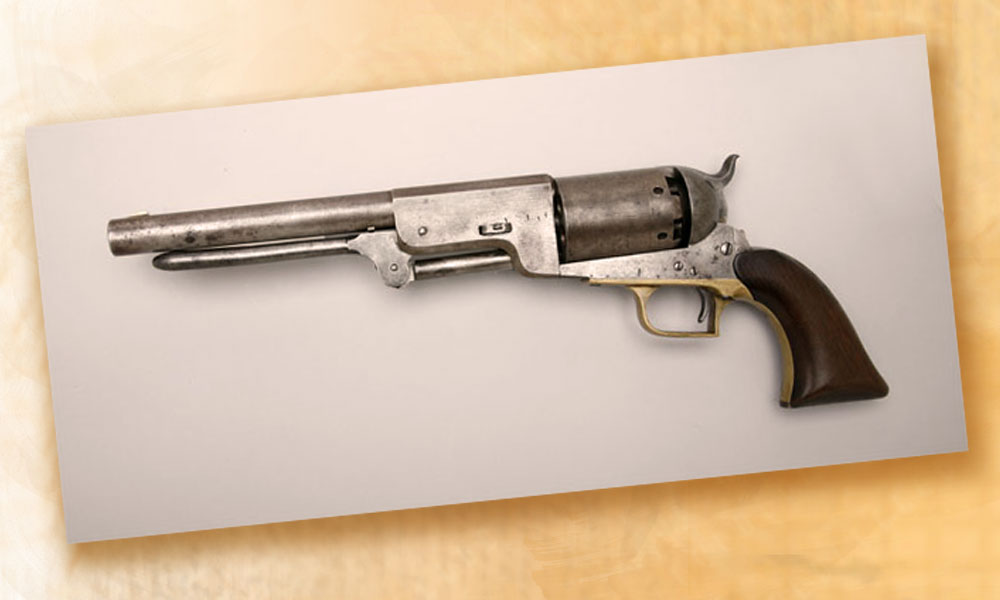

When Eastwood’s character ruthlessly killed those soldiers in 1976’s The Outlaw Josey Wales, he chose as his weapons of death the 1847 Colt Walkers from his belt holsters. It’s not surprising that Hollywood would have him draw Colt’s first six-shooter, as much of the credit for taming the Wild West is usually assigned to six-shooters and big-bore rifles. But had he met those soldiers at a poker table, Josey might have reached into his vest pocket for the little five-shot pocket revolver that played its own part in the saga of the American frontier.

That hideout revolver, the 1849 Pocket Colt, was the most produced of all Colt percussion arms. It also became the best selling handgun in the world during the entire 19th century.

Colt’s First Pocket Revolver

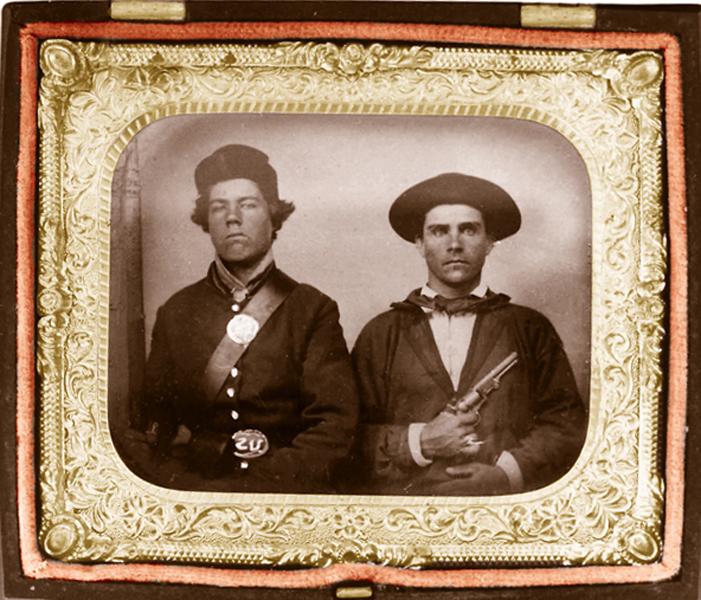

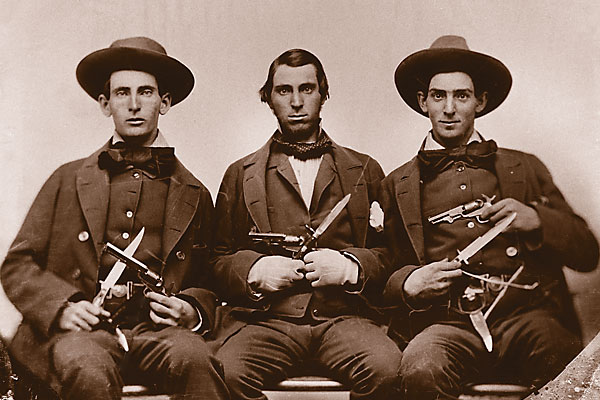

During the 1840s, people had a myriad of single shot pistols to choose from for personal portable protection. These guns varied from huge and cumbersome large-bored horse pistols to miniscule, largely ineffective “coat pocket” handguns. As insurance against malfunctions, some of these pistols were actually designed with auxiliary weapons such as affixed knives or heavy club-like handles.

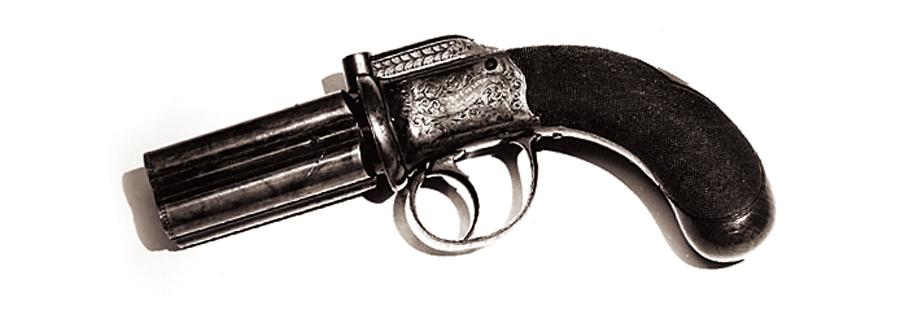

One of the few repeating pistols offered at the time, the multi-barrelled “pepperbox,” was a popular, but somewhat unreliable gun. Named for condiment canisters, a host of these single-action and double-action pepperbox pistols were produced by manufacturers including Allen & Thurber, Blunt & Syms and the English firm Manton. While some considered the pepperbox pistol one of the best pistols of its time, others saw it as unreliable, inaccurate and sometimes downright dangerous for its possessor. In his classic work Roughing It, Mark Twain claimed that the safest place to be when such a contraption fired was in front of it. A justice of the peace in Mariposa, California, agreed with Twain and actually ruled in an 1852 assault case that an Allen’s pepperbox could not be considered a dangerous weapon.

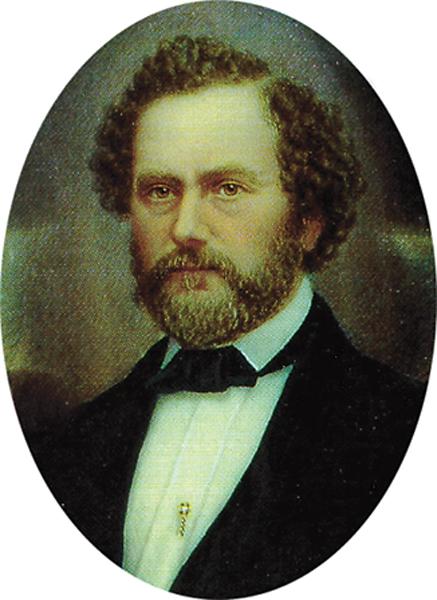

Lacking a truly reliable pocket-sized revolver, the public clamored for a quality, accurate weapon. Sam Colt, an astute businessman, knew he could fulfill the need. He carefully studied his big and heavy Dragoon revolver and determined that certain features deemed necessary in a large belt revolver could be removed from a smaller pocket-type pistol. In crafting his first pocket revolver, Col. Colt eliminated an estimated 85 of the roughly 480 separate operations required to produce his firm’s belt pistol, the .44 caliber Dragoon, reports P.L. Shumaker in Colt’s Variations of the Old Model Pocket Pistol, 1848 to 1872.

Colt’s first pocket revolver began production around 1847, after the collapse of his Patent Arms Manufacturing Company in Paterson, New Jersey. Now called the “Baby Dragoon,” this 1848 revolver was the predecessor to the 1849 Pocket Model. About 15,000 Baby Dragoons were the first pocket pistols produced by Colt’s facility in Hartford, Connecticut.

Colt offered these .31 caliber pocket pistols as an inexpensive repeating firearm designed to compare more favorably to the single-shot handguns then available. To cut costs, Colt replaced the traditional six-shot cylinder with a five loader. The Baby Dragoon also included a recoil shield but no safety cutout to catch a percussion cap. If a cap failed to ignite its chamber’s main charge, the pistol had to be dismantled to replace that faulty cap.

The model also lacked a rammer assembly underneath the barrel, which made loading a Baby Dragoon a cumbersome process. The shooter had to load ammunition by knocking out the barrel wedge and removing the barrel and cylinder. The shooter then charged the chambers of the cylinder with powder before utilizing the cylinder pin to force a lead projectile into each chamber. Next he fitted percussion caps over the nipples, replaced the cylinder and barrel assembly, and securely fastened the barrel wedge. Lastly, he rotated the cylinder so that the hammer rested over a single cylinder “safety” pin located between two of the chambers on the rear facing of the cylinder.

In spite of these drawbacks, Colt’s new pocket revolver still outperformed other available single-firing and multi-shot handguns in design, quality and function. The public’s approval was overwhelming, and the new little “revolving pistol” was a success from the very start.

Pocket Colt Shoots Out Competition

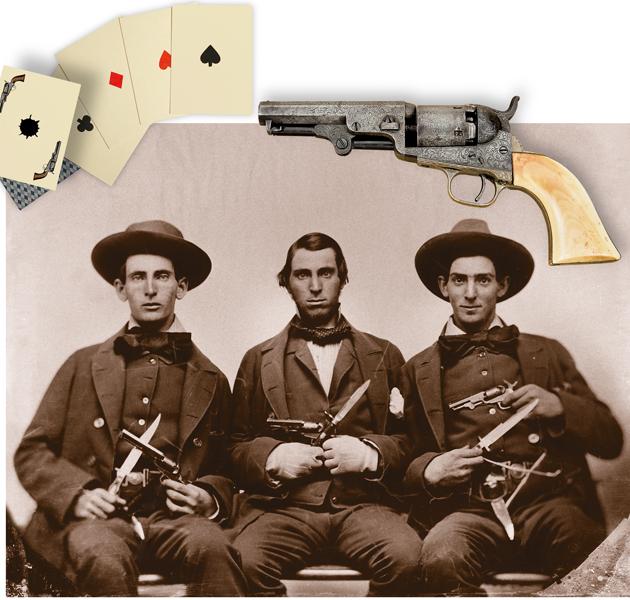

Public opinion spurred Colt to implement additional changes to the Pocket Colt (the first few had an estimated 150 run). Colonel Colt added a rammer assembly for easier loading and a cutout in the recoil shield so that capping could be accomplished without taking the pistol apart. Other improvements included affixing a roller bearing at the base of the hammer, placing tiny “safety” pins between each chamber, as opposed to just a single pin, and replacing rounded stops cutting into the cylinder with rectangular stops. Colt also lengthened the frame and barrel design, and modified the trigger and guard. The most notable cosmetic change made to the gun was engraving a “stagecoach holdup” scene by rolling it onto the cylinder. (Some early models, however, featured the “Ranger and Indian” fight scene as found on the Dragoon and Baby Dragoon models.) These features constitute what has become known as the standard 1849 Colt Pocket Model pistol.

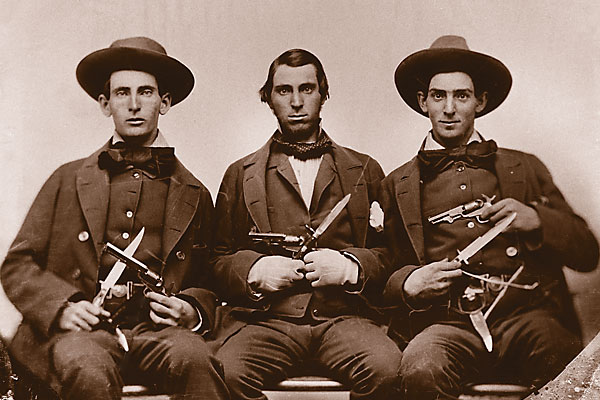

Produced in a wide variety of configurations and barrel lengths, the 1849 Pocket Model Colt became one of the most famous handguns of its time. It outsold all of the company’s other models as well as those manufactured by competitors. City dwellers in the East mainly purchased the five shooters for travel “insurance” and home protection. But many of these Pocket Colts also went west for California’s Gold Rush.

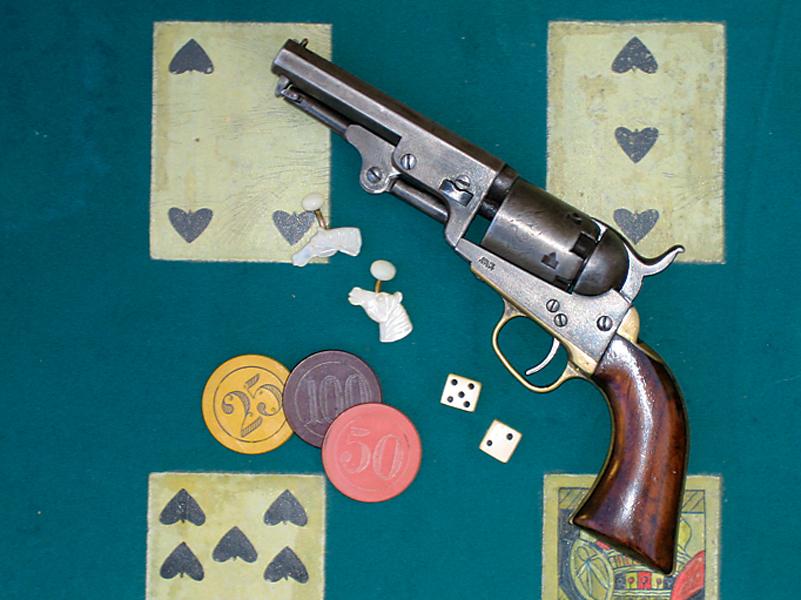

Initially promoted in California in March 1851, as the “New Pattern…with patent lever,” Colt’s improved ’49er quickly became a favorite with miners, express agents and other argonauts who needed a small pocket revolver. On San Francisco’s Barbary Coast, gamblers sometimes referred to such hideout guns as a “fifth ace.” The demand in the Golden State proved so great that Colt’s factory in Hartford was unable to keep up with the orders. The large belt model Colt, which sold for around $16-$18 each in the East, was selling for as much as $250-$500 apiece in the West. Even the less expensive .31 caliber model commanded prices around $100 on the West Coast. The gun proved to be a favorable alternative for folks who found the heavy Dragoon a bit inconvenient.

Many ’49 Colts made their way overseas. Thanks mostly to Colt’s British agency, the pistol reached ports in Canada, New Zealand, South Africa, Ireland, India and Australia. The demand “down under” was particularly strong due to the Australian Gold Rush of 1853-54. During the American Civil War, soldiers on both sides purchased the pistols with their own funds. They carried the 1849 Pocket models for close combat situations. For decades during the mid-19th century, adventurers worldwide praised these little Colts in the highest terms.

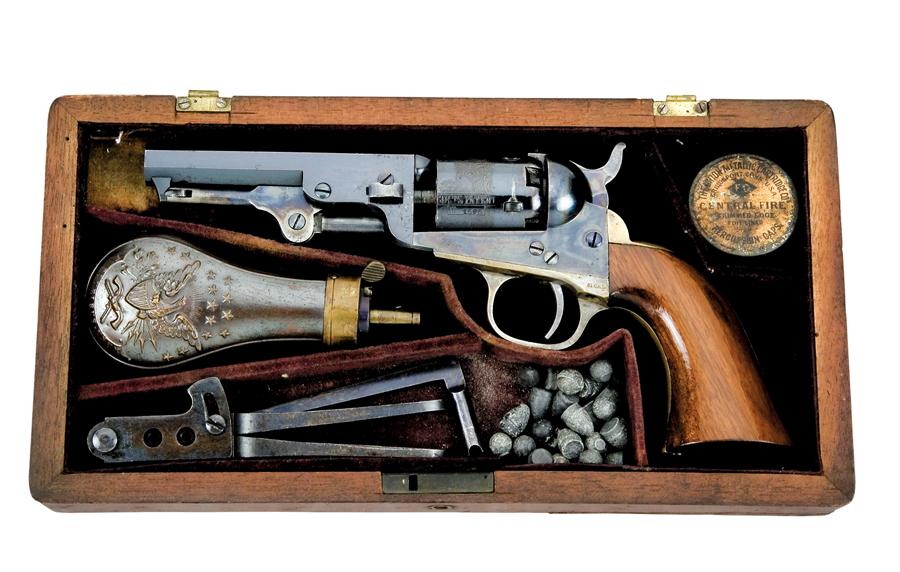

The ’49er was so well-regarded that many expressed their admiration for it by embellishing the Pocket Colt with custom stocks, special finishes, engravings and special gun sights. More non-standard Pocket ’49ers exist than any other model in the world, writes Robert M. Jordan and Darrow M. Watt in Colt’s Pocket ’49, Its Evolution, Including The Baby Dragoon & Wells Fargo. Jordan’s research shows at least 26,000 of the 1849 Pocket models were factory engraved and that more Pocket ’49ers are found in presentation cases than any other gun in the world.

The 1849 Pocket Model Colt may have outshot the competition, but it actually didn’t deliver much of a punch. Fortunately, it didn’t need to. The sidearm was perfect as leverage against a touchy situation. A misdealt card, a mining claim dispute, a defense of a lady’s honor or perhaps

an expedited bank withdrawal might all be eased along through the use of a ’49er. The simple brandishing of the firearm could even elicit the desired reaction.

If fired, the Pocket Colt’s efficacy varied at the whim of several factors not necessarily tied to its load. A .31 caliber round ball, or pointed (conical) bullet, weighs in at around 45 grains of pure, soft lead. With a standard charge of about 15 grains of FFFg (3Fg) blackpowder, this loading is capable of traveling at around 590 feet per second (fps) and hitting with a bit under 35 foot-pounds of muzzle energy. In comparison, a little modern .32 Smith & Wesson, when fired from a short-barreled revolver, develops approximately 680 fps and delivers almost 90 foot-pounds of muzzle thump.

By our current standards, the ’49 Pocket Colt is hardly impressive, but in its time, it could do damage. At close range, the length of a card table for instance, the gun could be dangerous. The soft lead of its bullets had the capacity to frustrate the period medical establishment.

Colt made the 1849 Pocket Model in barrel lengths of three, four, five and six inches. The four-inch and five-inch tubes were the most popular, and the six-inch barreled version appears to be the scarcest model produced. Unloaded, a ’49er weighs from 24 to 27 ounces, depending on barrel length. Sold with a blued barrel and cylinder, the frame and loading lever were color case hardened. Grip straps were generally silver plated over brass, although some were made with blued- or silver-plated iron. Factory standard stocks were of the one-piece varnished, straight-grained walnut variety—typical of commercially-produced period Colts. Custom stocks of select burl walnut, ivory and other materials were offered. On an 1849 model, you’ll likely find one of a variety of barrel roll stampings noting the addresses and places of manufacturing.

Although one of the Pocket Model’s improvements was the incorporation of a loading lever assembly, Colt produced a small number of ’49 models without these additions. Modern gun aficionados nicknamed these three-inch rammerless ’49ers the “Wells Fargo,” yet no evidence supports the claim that the famed express firm ever officially adopted this weapon as a sidearm for its drivers, guards and various agents. Wells Fargo employees certainly did carry ’49 Pocket Colts,

both with and without rammers. Many of these were privately purchased, along with other sidearms.

In any event, the rammerless Colt ’49 never sold well. Sometime around 1860, Colt attempted to sell the remaining inventory of his pocket pistols without rammers by fitting these three-inch barreled revolvers with loading assemblies. These were made by crudely modifying loading levers from the standard four-inch barreled pistols. In spite of this modification, the guns still met with public disapproval as the altered rammer lever made it difficult to apply the proper pressure to the rammer itself. Colt manufactured relatively few of these guns, probably around 100. As such, these factory-modified Colts are extremely desirable pieces with today’s collectors.

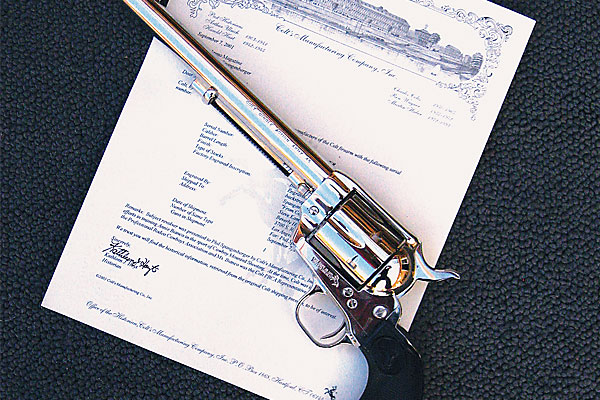

During its 23 years of production, Colt’s Hartford facility manufactured about 320,000 Colt Pocket Models, while another 11,000 were produced at the plant in London, England. Production of this handgun finally halted in 1873, when Colt began producing self-contained metallic cartridge revolvers. Despite the transition from cap-and-ball to metallic cartridge arms, Colt’s factory records reveal that percussion model ’49ers were still being shipped as late as 1889. This was especially ironic because the 1849 Pocket Model was one of the caplock revolvers that the Colt factory converted during its first stages of producing metallic cartridge handguns as early as 1869. A Colt employee, E. Alexander Thuer, designed a conversion system that allowed specially designed cartridges to be front-loaded. This little revision legally skirted around the Smith & Wesson-held Rollin-White patent for a drilled-through chamber in the revolver’s cylinder.

A Collector’s Dream

Inevitably, newer and stronger designs in pocket handguns and ammunition pushed the ’49 Pocket Colt to the wayside in favor of more modern arms. Today, the ’49 Pocket Model is considered quite collectible, commanding premium prices among discerning arms collectors. Greg Martin Auctions in San Francisco, California, set a record for the highest price paid at auction for a firearm when it sold a cased, gold-inlaid 1849 Pocket Colt engraved by Gustave Young for a $720,000 bid in 2003.

With the original garnering such a commanding price, it’s not surprising that variations of the 1849 Pocket Colts are still manufactured by Italy’s A. Uberti and Company, the world’s largest replica house, and sold by Cimarron Fire Arms, Uberti (Benelli USA), Taylor’s & Company, E.M.F. Company and Dixie Gun Works. The firms offer the standard four-inch barreled 1849 Model, the so-called “Wells Fargo” model (sans rammer assembly) and the rammerless Model 1848 “Baby Dragoon.” The Pocket models can be purchased from either company in a variety of standard finishes that include dark blue, charcoal blue and the so-called “original” antique patina.

Shooting one of these replica 1849 Pocket Model Colts is a true joy. The attached rammer assembly on Cimarron Fire Arms’ replica of the four-inch barreled version makes loading easy and firing the gun delightful. Unlike the big belt model cap-and-ball six-guns of the age, you won’t hear a booming report or see as much white smoke with each shot. Discharging this little spitfire is rather reminiscent of a small vocal dog. The diminutive wheel gun barks sharply, spitting out a .31 caliber ball with the gusto of a feisty little critter. At close range, say within 25 feet, the accuracy is gratifying. At card table distances, the ’49er is deadly, putting its lead pills right where they are aimed.

After handling and firing this pocket revolver, one can easily see why it commanded such respect among the people of the Victorian era. For its time, the 1849 Colt Pocket Model was a modern and practical pocket gun. And no bluecoat whistling “Dixie” in your face would have stood a chance against it.

Photo Gallery

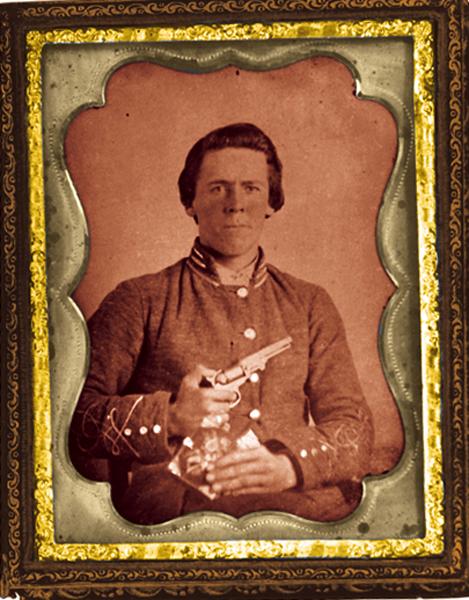

– Courtesy Herb Peck, Jr. Collection; Four-inch

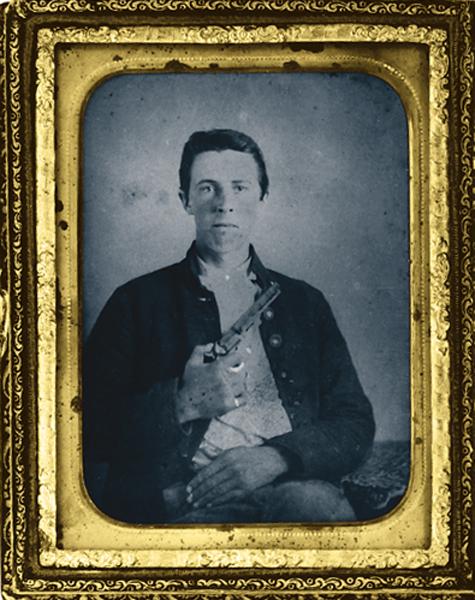

– Courtesy Herb Lyman Collection –

– True West Archives –

– True West Archives –

– Courtesy Little John’s Auction Service / Anaheim, California –

– True West Archives –

– Courtesy Little John’s Auction Service / Anaheim, California –

– Courtesy Phil Spangenberger Collection –

– Courtesy Herb Peck, Jr. Collection –

– True West Archives –