August 12, 1881

The Clanton Camp: Innocent Cowboys or “a Viper’s Nest” of Outlaws?

A group of some 25 American cowboys has been raiding in Northern Sonora, Mexico, gathering all the loose stock they can find before starting home. A Mexican posse from Bavispe is sent to overtake them but is turned back with eight casualties.

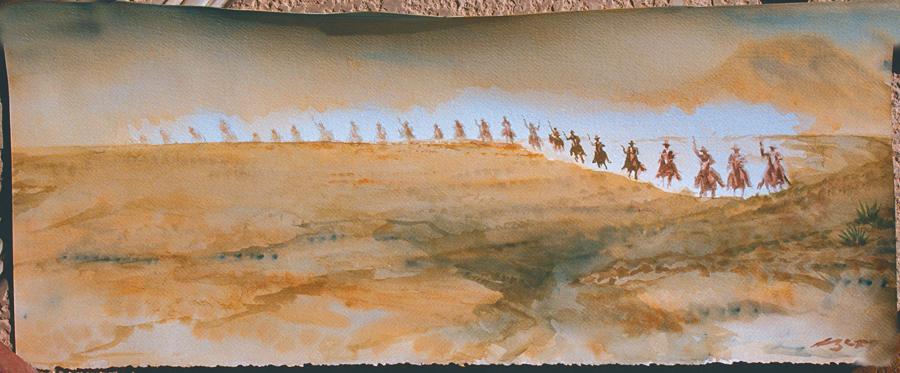

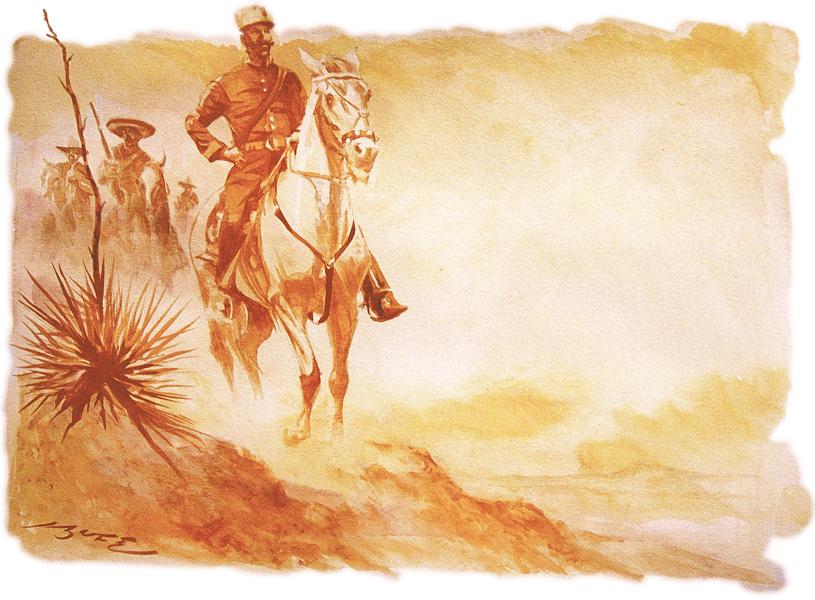

Now, Capt. Carrillo leads his 50-man militia on a border trek to track the cowboy raiders and their illicit herd.

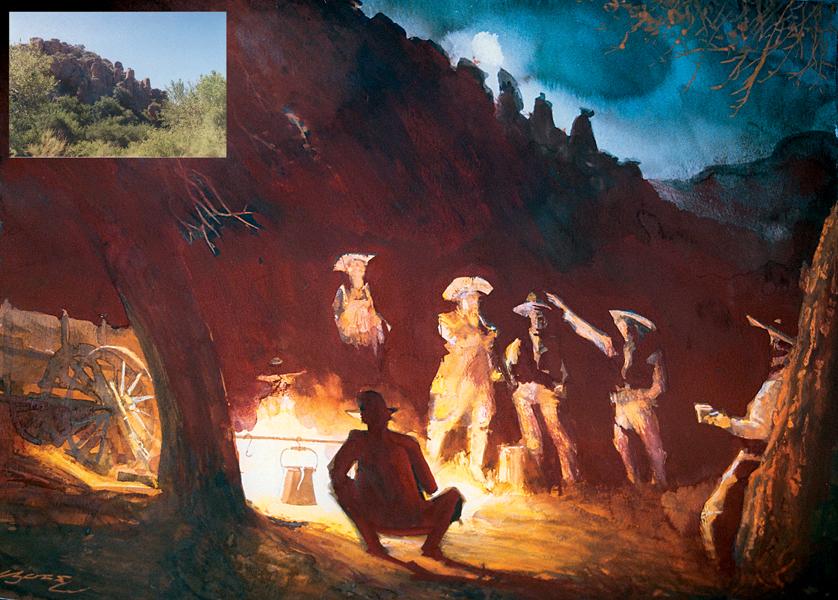

In Guadalupe Canyon, a bit north of the Mexico border marker, Old Man Clanton and five other cowboys stop for the night with a cattle herd.

Just past midnight, stage robber James Crane rides into Clanton’s cow camp. After some small talk, he and the cowboys bed down.

During the night, cowboys Billy Lang and Charles Snow are awakened by stirring cattle.

The cows are likely responding to the intrusion of Mexican troops, who have followed the cattle rustlers’ tracks to the canyon. Spotting the Clanton cow camp, the posse members have stealthily surrounded the camp, waiting for the right time to strike.

After Lang and Snow conclude a bear must be nearby, upsetting the herd, Harry Ernshaw tells Snow to grab his gun and drive the animal away.

As Snow crawls out of his bedroll with his weapon, shots ring out from the surrounding bluffs. He is immediately hit and falls to the ground.

Before Old Man Clanton, Crane and Dixie Lee “Dick” Gray can even respond to the ambush, they are killed in their bedrolls. Ernshaw and another cowboy, William Byers, escape, but just barely.

William Byers’ Description of the Ambuscade:

“When they first fired and killed Charley Snow I thought the boys were firing at a bear. [I] jumped out of my blankets, and as I got up the boys around me were shot. As soon as I saw what was up I looked for my rifle, and not seeing it I grabbed my revolver, and seeing them shooting at us from all sides, started to run, but had not gone forty feet when I was shot across my body, but I didn’t fall, and in a few more steps was hit in my arm, knocked the pistol out of my hand and I fell down.”

Byers then describes playing dead: “When I saw the Mexicans begin stripping the bodies, I took off what clothes I had, even my finger ring, and lay stretched out with my face down, and as I was all bloody from my wounds, I thought they would pass me by, thinking I was dead, and had already been stripped. I was not mistaken, for they never touched me, but as one fellow passed me on horseback he fired several shots at me, one grazing the side of my head, and the others striking my side, throwing the dirt over me. But I kept perfectly still and he rode on.”

—Tombstone Nugget report, as reprinted in the Arizona Weekly Star on September 1, 1881

The Back Story

On August 1, 1881, a party of 16 Mexicans from the interior of Sonora, Mexico, are attacked about 30 miles south of the border, near Fronteras. Allegedly, some 25 American cowboys attack them, killing four, and seize the Mexicans’ mules, pack saddles and a reported $4,000. These cowboys are also suspected of raiding and plundering throughout the region.

In early August, 30 Mexican vaqueros cross the border and ride into New Mexico’s Animas Valley to round up several hundred head of cattle. As they return home, they are overtaken by 25 American cowboys bent on retrieving “their” stock. A running fight ensues “on the plains near” Guadalupe Pass, where the Mexicans give up the cattle and retreat across the border.

One of the cowboys from the area, John Plesent Gray, admits late in life that the Mexicans were not rustlers. They were merely retrieving cattle stolen from them in the first place.

After the battle, the Tucson Citizen reports that “the citizens of Babispe [Bavispe, Mexico] are after the cow-boys and are disposed to take summary vengeance if they overtake them.”

The Clanton Camp: Innocent Cowboys or “a Viper’s Nest” of Outlaws?

Old Man Clanton was traveling with five drovers, which is 19 less than the reported number of raiders in Mexico.

Other than James Crane, who is a suspect in the March 15, 1881, robbery of a stage bound from Tombstone, Arizona, to Benson, none of the cowboys in the camp are known outlaws. One is a dairy farmer, three are mere boys and another, Dixie Lee Gray, is described as “the lame one.”

In spite of later attempts by writers to portray this group as “a viper’s nest” of outlaws, it seems more likely these cowboys are only guilty of being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

The Gray Account

“After the firing commenced [Harry Ernshaw] concealed himself behind a large brush and emptied two revolvers at the assailants. At this time he was joined by Billy Lang, and they concluded to try to escape and started to run, when the Mexicans opened a full volley at them and Billy fell. The bullets whistled all around him one grazing the bridge of his nose, but he succeeded in getting away without any further injury and made his way back to Lang’s ranch. Immediately upon his arrival there the boys at the place hurried to the scene of the killing and found the bodies of five men. They then commenced to search for Billy [Byers] and found that he had been taken in by a rancher near by, but had in a fit of delirium again wandered off. In a short time they found him in an exhausted condition, and took him to Lang’s ranch.”

—John Plesent Gray, brother of the dead Dixie Lee, as reported in the Tombstone Nugget

The Deadly Tally

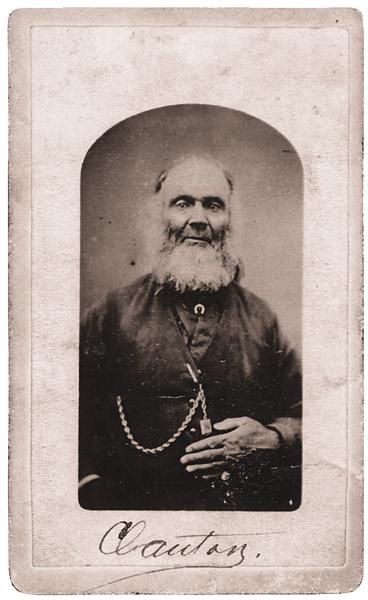

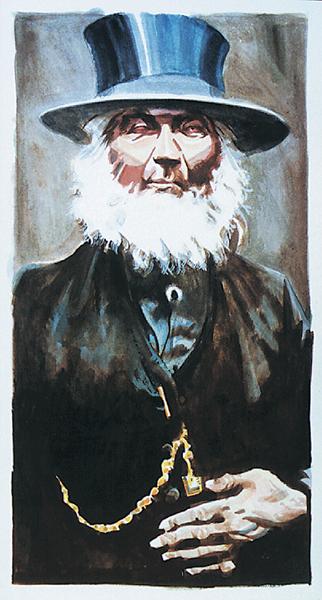

Old Man Clanton

(killed)

Dixie Lee “Dick” Gray

(killed)

William Byers

(wounded)

Billy Lang

(killed)

Charles Snow

(killed)

James Crane

(killed)

Harry Ernshaw(wounded)

Did Wyatt Earp Lead a Super Posse Against Old Man Clanton?

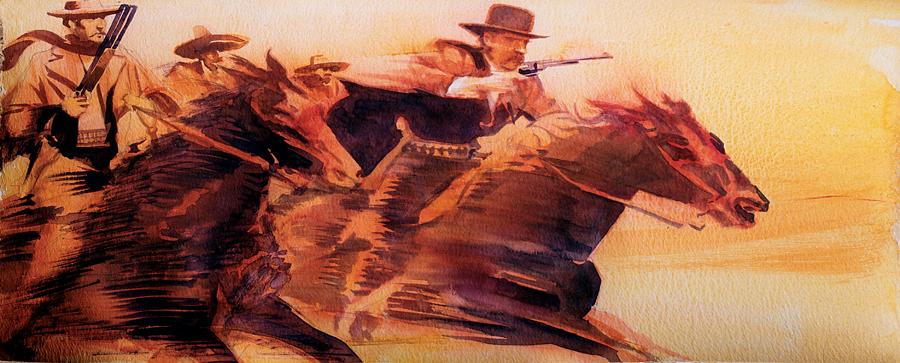

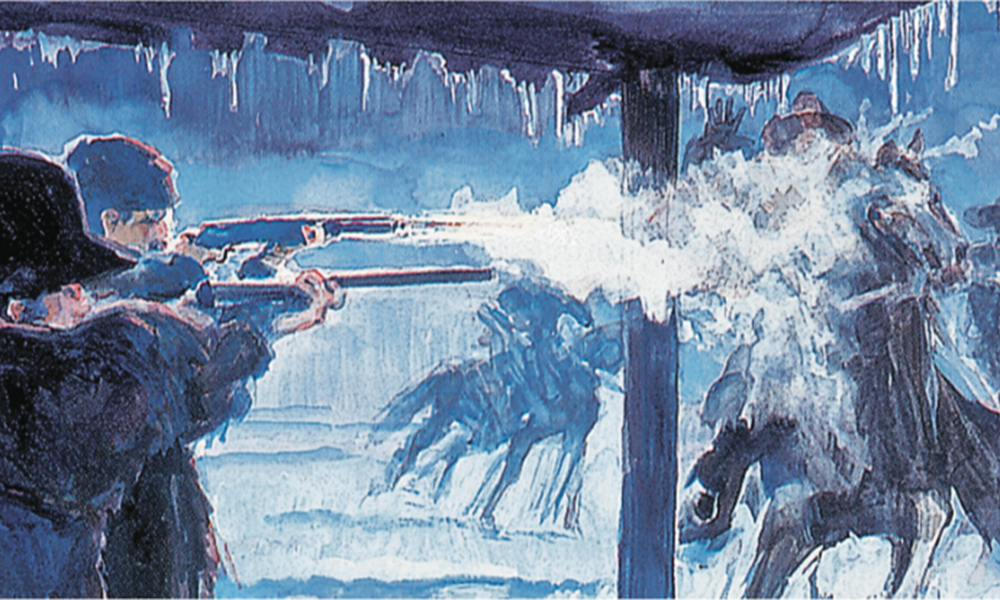

On the thinnest of evidence, some Earp buffs have glommed onto a conspiracy theory that puts their heroes, Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday, behind the sights of the ambush guns (above).

The buffs cite local tradition (“My grandfather told me.”) and two contemporary references:

• An August 18 editorial by Tombstone Epitaph editor John Clum: “If the officers of the law cannot enforce the law, they should turn over the responsibility to more willing hands.”

• An excerpt from U.S. Marshal Crawley Dake’s August 5 report to the attorney general: “Have sent a deputy and posse after the cowboys.”

From these vague references, Earp buffs make the leap of imagination that Wyatt and a “hybrid posse” made up of Federal agents and Mexican troops were sent on a secret mission to wipe out a “viper’s nest of cowboys,” as Earp author Timothy Fattig puts it. Fattig also maintains that the activities of the Earp posse were “highly irregular and … kept as secret as possible.” So secret that the attackers allegedly killed the Clantons in Skeleton Canyon, not Guadalupe Canyon. The supposed rationale for moving the site of the fight was to avoid an “international incident of the worst kind.”

In my opinion, this theory is wishful thinking of the worst kind.

Adherents to this questionable theory include authors Glenn Boyer, Ben Traywick, Timothy Fattig and Karen Holliday Tanner.

Old Speculation vs New Speculation

For over a century, many writers and historians have taken it on face value that Old Man Clanton and his cowboys were rustling cattle in Mexico. They claim that after crossing the U.S. boundary line with their plunder, the cowboys assumed they were safe and camped for the night. The resulting ambuscade is seen as a righteous comeuppance.

Fast forward to the O.K. Corral gunfight in October 1881. Two of the combatants, Ike and Billy Clanton, have a reputation (as does the entire clan) that has, at least on paper, been “juiced up,” casting the Clantons as outlaws of the first water. Beginning with Walter Noble Burns’ 1927 book Tombstone, Old Man Clanton is portrayed time and again as a Cowboy Kingpin or Sagebrush Godfather, said to be the power behind all the illegal cowboy activity in Cochise County.

But was he really? Consider this: Newman Haynes Clanton was never charged with any crime, and he was quoted and portrayed in contemporary newspapers as a solid citizen. Of course, Old Man Clanton was no angel (two of his nefarious sons were living proof that acorns don’t fall far from the tree).

Thus, it is conceivable that even if the old man didn’t directly participate in the raids, he may have benefited by buying illicit beeves and/or profiting from the plunder. Adherents to this theory point to outlaw James Crane’s presence in his camp as the proof in the pudding. They believe that Crane rode into the cow camp to give Old Man Clanton his cut (this is mere speculation on their part, as is the hypothesis of Clanton’s innocence). But, as John Plesent Gray wrote in his memoirs, outlaws stopped at almost all the ranches.

If the Clanton group really was returning from Mexico with stolen beef, it’s very unlikely they would have camped right on the border. It only makes sense that the cowboys stopped at this unfortunate spot when you take into account that the group was traversing the canyon from the Lang Ranch in New Mexico (it’s a logical stopping point, going east to west or vice versa).

Of all the cowboys in Guadalupe Canyon that night, James Crane is the most likely to have participated in the raiding. He is presumed to have taken part in the unsuccessful Benson stage robbery in March and in killing the Haslett brothers in Eureka, New Mexico, in June (see Classic Gunfights, October 2003).

What Crane was doing riding through Guadalupe Canyon at midnight will probably never be known, but we do know one thing: he brought death with him.

Aftermath: Odds & Ends

The commander of the Sonoran troops, Mexican Gen. Adolfo Dominguez, visited Tombstone, Arizona, on August 19 to call for a joint U.S.-Mexico effort to catch the rustlers. “The American raids did much damage in our country,” Dominguez said, “and affairs have been gradually growing more and more desperate. It is estimated that within the last month more than ten citizens have been killed and upward of $30,000 worth of property taken. We do not believe that this disposition to raid is general among citizens of this section.”

Although newspapers throughout Arizona and the West warned of amassive cowboy retaliation against Mexico, it never materialized. When Chester A. Arthur took over the presidency in September, Arizonans were more fearful of war with the Apaches.

After the death of James Crane, Wyatt Earp’s deal with Ike Clanton fell apart. Clanton had previously agreed to turn over the robbers of the Benson stage—Bill Leonard, Crane and Harry “The Kid” Head— for the reward, and Earp would have gotten “the glory,” which he hoped would get him elected sheriff of Cochise County. Leonard and Head were already dead, having been killed by other cowboys a month earlier (see Classic Gunfights, October 2003). If Earp really was in on the Guadalupe ambush, wouldn’t he have claimed his “glory”? (See sidebar on opposite page to find out why I believe he wasn’t involved.)

Recommended: Wyatt Earp: The Life Behind the Legend by Casey Tefertiller, published by John Wiley and Sons, and The Real Wyatt Earp: A Documentary Biography by Steve Gatto, published by High Lonesome Books.

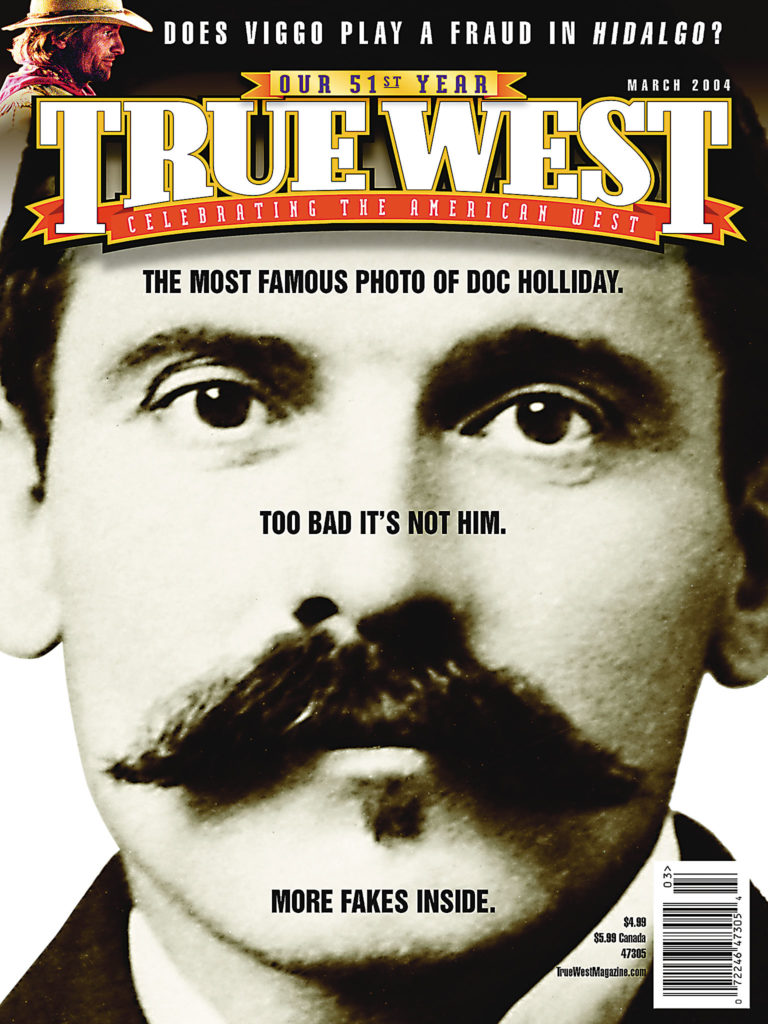

Photo Gallery

– By Bob Boze Bell –

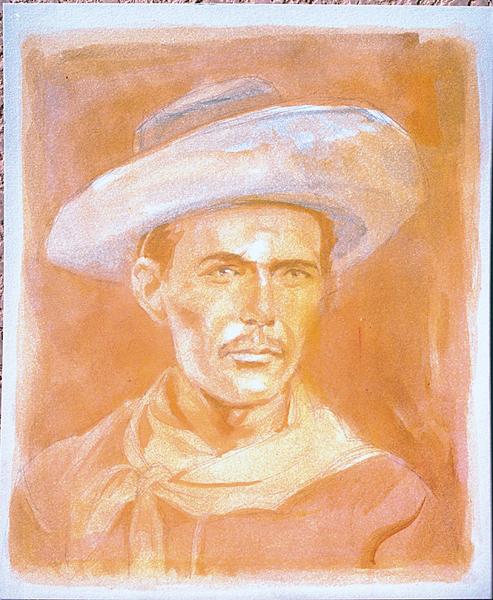

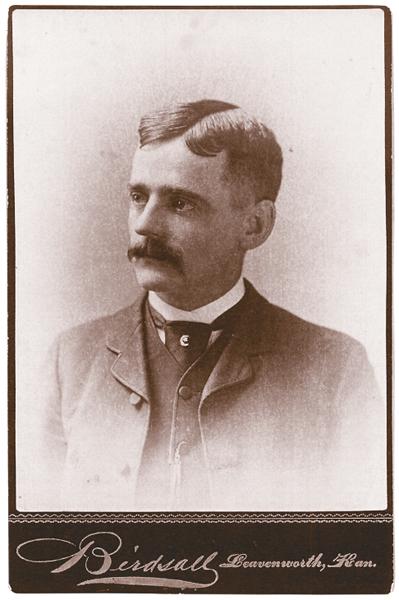

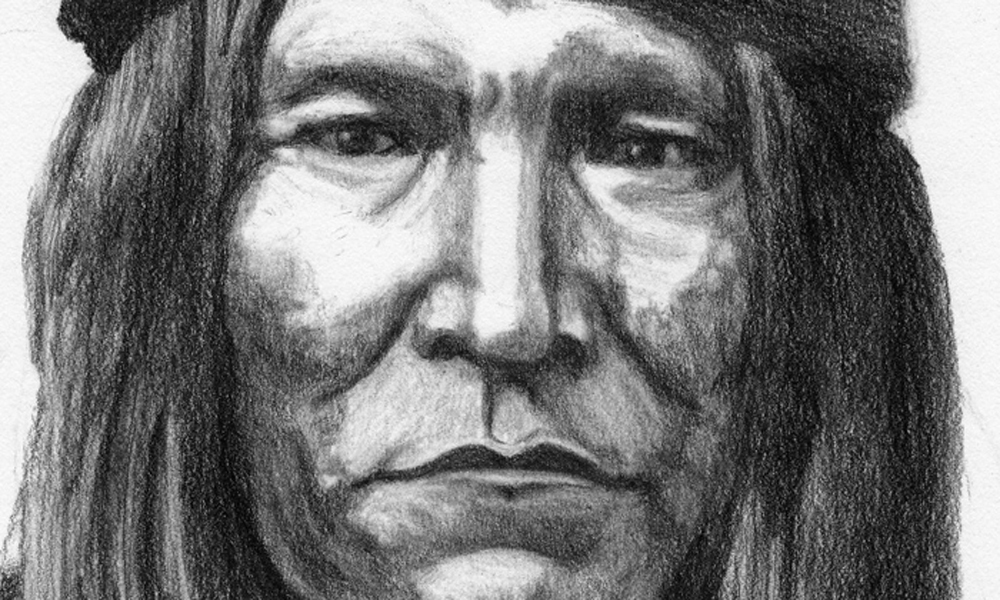

James Crain [or Crane]: American; about 27 years old; about 5 feet, 11 inches high; weight, 175 or 180 lbs.; light complexion; light, sandy hair; light eyes; has worn light mustache; full, round face, and florid, healthy appearance; talks and laughs at same time; talks slow and hesitating; cattle driver or cow-boy.

—Sacramento Daily Record-Union, quoting Gen. Adolfo Dominguez, the commander of the Mexican troops in Sonora-

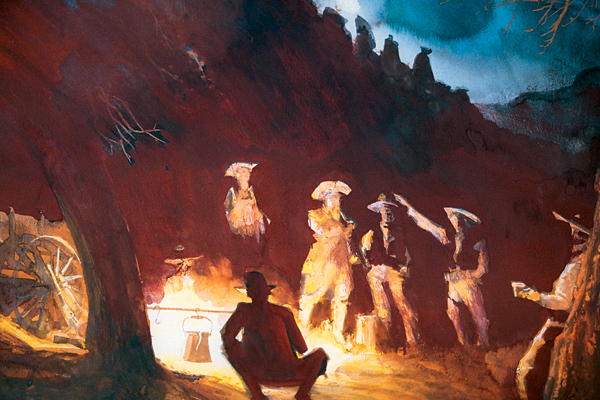

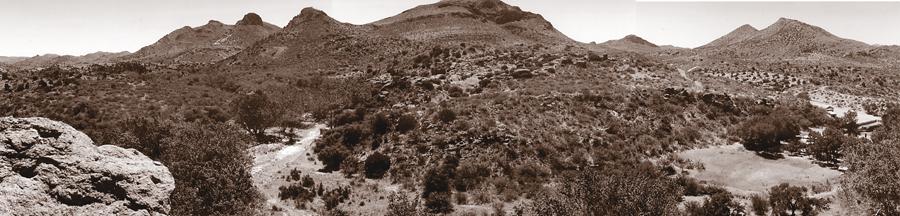

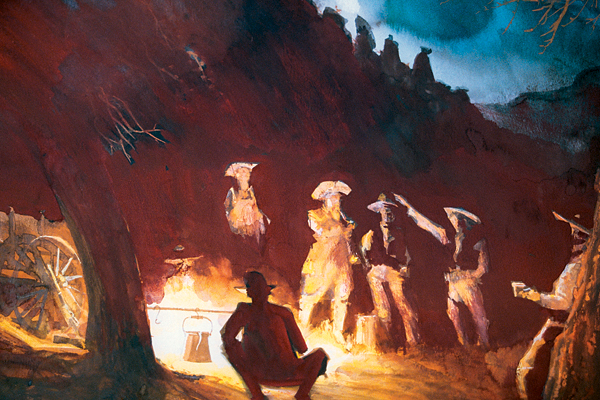

On the night of August 12, a lone rider visits the Clanton cow camp in Guadalupe Canyon (above). Not long after, a group of Mexican soldiers takes up positions on the surrounding bluffs. The troops hide behind distinctive rock outcroppings, which are seen in this modern photo of the battle site (right).

– All illustrations by Bob Boze Bell –

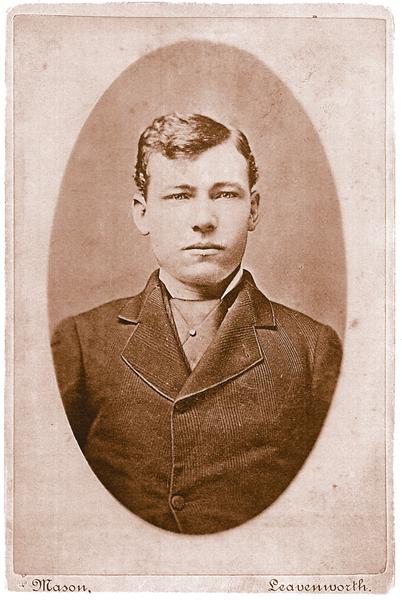

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin –

On the thinnest of evidence, some Earp buffs have glommed onto a conspiracy theory that puts their heroes, Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday, behind the sights of the ambush guns (above).