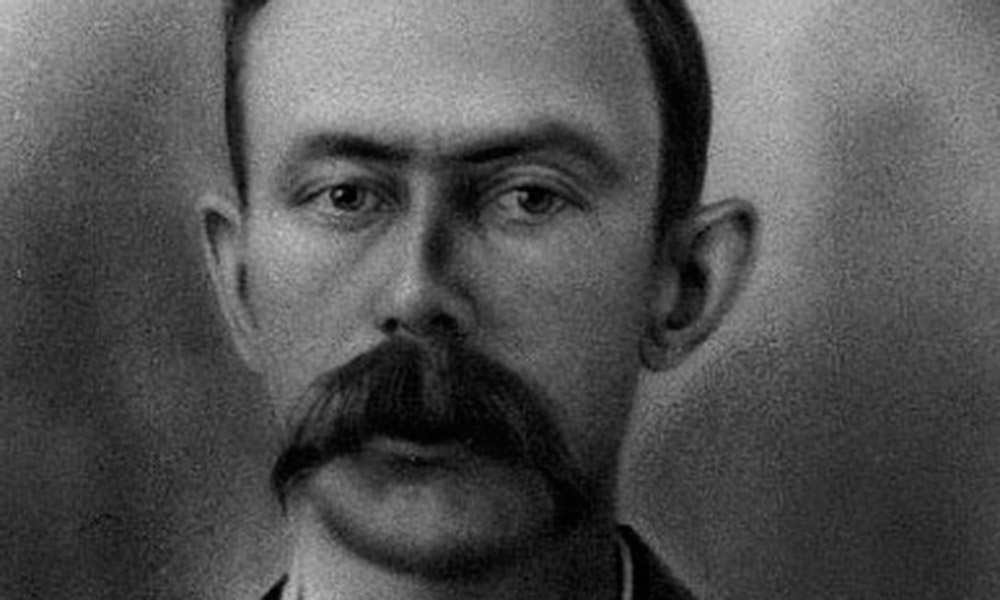

In the midst of a prisoner exchange negotiation, two men enter William Clarke Quantrill’s camp, four miles northeast of Lee’s Summit, Missouri, about three miles east of Little Blue River, on August 28, 1862.

In the midst of a prisoner exchange negotiation, two men enter William Clarke Quantrill’s camp, four miles northeast of Lee’s Summit, Missouri, about three miles east of Little Blue River, on August 28, 1862.

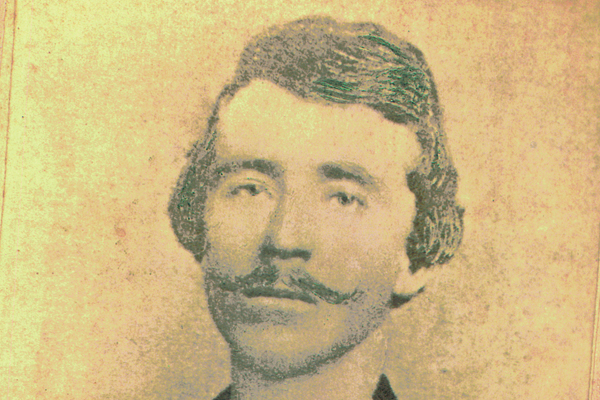

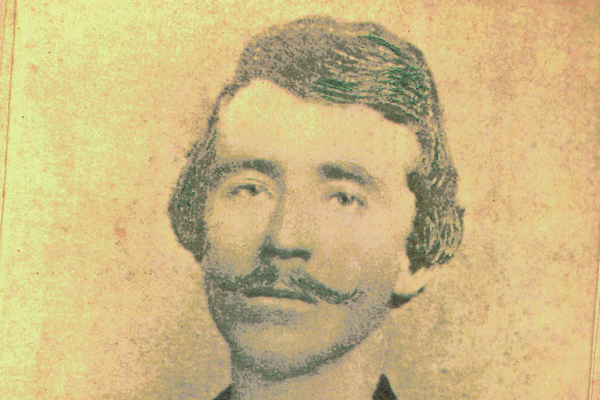

They have come to deliver a recent issue of the Missouri Republican to the guerrilla leader. Confederate 3rd Lt. William H. Gregg watches as his leader reads the news, which reports that military authorities in Fort Leavenworth have executed Quantrill’s close friend, Perry Hoy.

“Suddenly I saw a change in Quantrill’s countenance, and the paper fell from his hand,” Gregg writes in his manuscript. “Without saying a word, he drew a blank book from his pocket, penned a note on a leaf, folded and handed it to me, saying ‘Give this to [Andrew] Blunt.’”

The note states, “Take Lieut. Copeland out and shoot him.”

Quantrill also orders two more Federal prisoners shot. After the orders are carried out, Gregg writes that Quantrill tells his men to saddle up, saying, “We are going to Kansas and kill ten more men for poor Perry!”

Quantrill’s Vengeance

In the summer of 1862, Federal soldiers from the Second Kansas Cavalry captured Perry Hoy of Kansas’ Johnson County—one of the original members of Quantrill’s Confederate guerrilla band. The soldiers charged him with the murders of a First Missouri Cavalry sergeant and a toll keeper of a bridge over the Little Blue River, southeast of Kansas City.

Quantrill had sought to free Hoy by offering an exchange of Lt. Levi Copeland, a Federal prisoner captured during the Confederate victory in the Battle of Lone Jack, Missouri.

With the death of his friend on his mind, Quantrill led his 140-man party on September 6 to Olathe, where the Union Army had recently recruited new soldiers for the 12th Kansas Regiment’s Company H. The men were scheduled to leave Olathe in a few days. Quantrill and his men knew many of the recruits, as well as where they lived.

Six miles east of Olathe, the bush-whackers dragged a recent enlistee named Frank Scott from his bed. They killed him and left his body in a gully down the road. One of the men who shot Scott described the “mental agony of the poor victim at the thought of never seeing his little family again, and [mimicked] his prayers and petitions for mercy,” reported L.W. Thavis in the January 15, 1897, Olathe Weekly Herald.

The raiders also stopped at another cabin, capturing John and James Juda, brothers who had also recently joined the Federal army. When the band entered the Juda household, they ransacked the home while “cursing, singing and making sarcastic remarks about ‘Happy Kansas,’” Thavis reported. The Judas’ dead bodies were found not far from their house the next morning.

When the band reached Mill Creek three blocks east of the county courthouse, Quantrill sent Gregg and 60 of the men to cordon off the town. The rest of the bushwhackers, some wearing Union uniform coats as disguise, rode directly into the town square.

“Do not let a man escape”

At first, townsfolk mistook them for a Union Cavalry company. William Roy, the post adjutant, first noticed the riders and hailed them, “Is this Captain Harvey’s command?” Thavis reported. One of the riders answered, “Yes.”

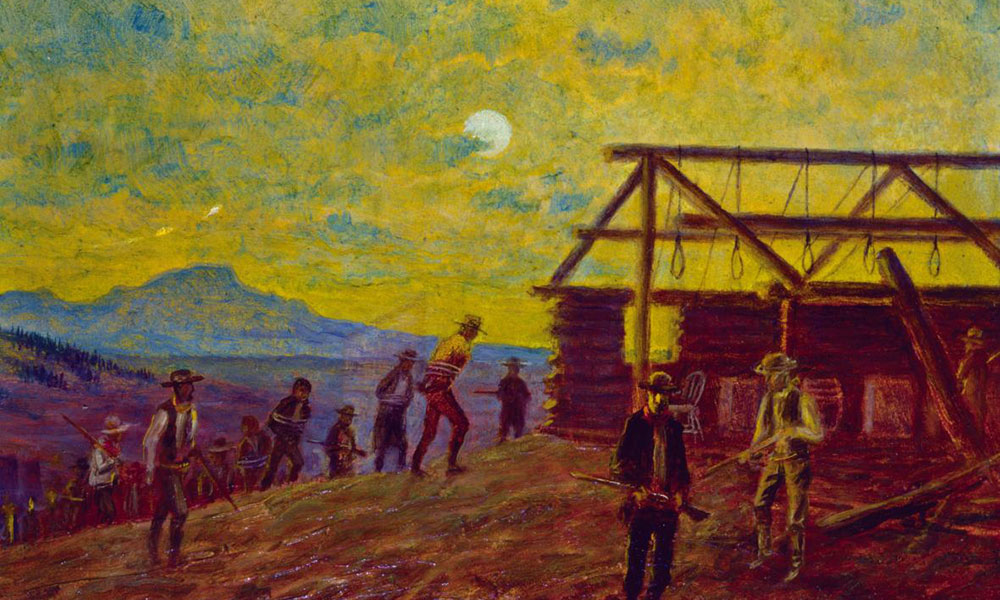

Having entered the town without meeting resistance, the bushwhackers stopped on the south side of the square, where, according to Thavis, Olathe’s constable J.H. Milhoan heard Quantrill give the order, “File right, file left. Take immediate possession, and do not let a man escape.”

Only then did observers realize that Quantrill’s men had invaded the town. The bushwhackers stopped on the dirt street in front of a stone building that housed a saloon on the northeast corner of the square. As if ready for battle, 124 Union recruits were already lined up in the square, Gregg wrote.

Quantrill’s men “hitched their horses close together to the fence around the courthouse, then stood in a line facing the Union volunteers on the other side of the square,” writes Duane Schultz in Quantrill’s War. “As soon as they had formed into that closely packed line, they drew their revolvers, each man holding two, and told the Yankees to surrender.”

All but one soldier surrendered without firing their weapons; the bushwhackers immediately shot the one who resisted.

Spring Hill merchant Hiram Blanchard was one of the saloon patrons who raced out onto the street. He tried to stop the guerrillas from taking his fine draft horse by grabbing the bridle rein and trying to mount the horse. A musket charge blew off the top of Blanchard’s head.

The guerrillas entered every house and business in town, breaking doors and windows. They rousted all the townsmen out of their beds and herded them onto the courthouse square along with the Federal soldiers. While bushwhackers ransacked the two-story frame building that housed Union recruits, several recruits died, including two in their sleep.

The destroyed businesses included both offices of the town’s newspapers: the anti-slavery Olathe Mirror and the Olathe Herald, which had Southern sympathies and may have been attacked in error. Local lore has it that the bushwhackers first attacked the Herald, thinking it was the Mirror. When the mistake was discovered, the bushwhackers demolished the Mirror’s offices, as well.

The only business left untouched was the Olathe Hotel run by the Turpins, a family of Southern sympathizers whose younger son Cliff was riding with Quantrill’s raiders. Cliff’s mother had traveled to Missouri the previous day and returned to Olathe the night of the raid. Some speculate that she played a role, perhaps furnishing information to the band.

In addition to taking over the town, the guerrillas looted surrounding farms. At the Mahaffie farm, they found the doors unlocked. “Lucinda Mahaffie left the front door wide open,” says Phil Campbell, historic programs coordinator of Mahaffie Stagecoach Stop and Farm historic site. “She also opened all the kitchen cupboards and left the kitchen door ajar.”

Campbell says Lucinda wanted to make it easy for Quantrill’s men to find what they wanted, reasoning that they might be inclined to leave the rest of her things alone. She sent her older children to chase the horses to the back of the farm to keep them from the raiders. She then accompanied the rest of her six children to the north end of the farm to hide until the guerrillas left.

Lucinda’s quick thinking paid off. The bushwhackers emptied the cupboards and took some silver pieces, but they left everything else undisturbed. No historical record mentions the whereabouts of Lucinda’s husband, Beatty. Campbell speculates that Beatty could have been in town or returning from a business trip. He was at least near the area because Ed Blair mentioned him in 1915’s History of Johnson County, Kansas, as accompanying neighboring farmer Jonathan Millikan into town the morning after the raid.

The Morning After

In the morning, an older farmer named William “Noble” Carruthers slipped away from the square and raced home to bury his savings of $1,500 in gold coin, wrote Thavis in the Olathe Weekly Herald. Carruthers finished burying the gold in the stable just as he heard three or four bushwhackers approach. He rushed into the chicken coop and emerged carrying several chickens.

One of the bushwhackers asked, “What in the hell are you doing with those chickens?”

Carruthers answered, “I thought perhaps you might want breakfast before leaving and will have some chickens cooked ready.”

The men left, and Carruthers’ fortune remained undiscovered.

In town, Quantrill’s bushwhackers corralled every man in the square and separated citizens from the Federals. During this time, Quantrill recognized an old acquaintance, E.W. Robinson of Paola, Kansas, in the crowd.

“Quantrill recognized me among the prisoners, invited me outside the corral, to a seat beside him [on a fence] surrounding the public square, where we talked for more than an hour,” wrote Robinson in a May 9, 1881, letter to W.W. Scott. “During the conversation, I addressed him once as ‘Bill’ —he very politely requested me to address him as ‘Captain Quantrill,’ and took from his pocket and showed me what he claimed was a commission from the Confederate Government, but I did not read it —being an old acquaintance, and having no grudge against me, he treated me kindly.”

To Shoot or Not to Shoot

During the two-day foray, the guerrillas had killed or injured more than 20 citizens and Union soldiers. They filled six wagons with food, clothing, money, jewelry and 100 Union muskets and thousands of rounds of ammunition intended for the new Union recruits. They also took all the photographs of young women they could find—an activity not reported in raids on any other northeast Kansas town. The raiders later discarded the muskets, which Thavis wrote, “were of a pattern rather popular with the war authorities in those days—equally dangerous at either end and warranted to hit anything but the object aimed at.”

Quantrill and his men left the civilians in town and marched the Federals—stripped to their underwear—toward Spring Hill. Instead of killing them, as many feared, Quantrill released them to Union Lt. William Pellett, who was among the group. Pellett, who was a recruiting officer at the time, was the smallest man in the group.

Quantrill’s men stopped for breakfast in Squiresville, according to Pellett’s account recorded in Blair’s History. After they ate, the prisoners formed up into a straight line. Quantrill, mounted on horseback, motioned Pellett to step out of line.

After the two shook hands, Quantrill said, “I’ve been doing something the last half hour I very seldom do. I have been making up my mind whether to shoot you or not.”

“Captain, what conclusion did you come to?” Pellett asked.

“I have come to the conclusion,” Quantrill said, which Pellet reported is when the guerrilla leader took a long pause, “not to kill you. When we left Missouri, I had the purpose of killing 10 men, and I have filled my bill.

“Now in a short time, my men are going to leave here. Before we leave, or about the time we leave, you get these men out of here,” said Quantrill, according to Blair’s History.

After the Federals took an oath not to raise arms against the Confederacy, Quantrill told them, “Return home and be good boys.” The soldiers walked back to Olathe unharmed, reaching home around noon. (Pellett became Olathe’s first mayor when the town became a city of the second class in 1870.)

“They took everything”

Quantrill and his men returned to Missouri, but their effect on Olathe was profound. “They took everything,” Olathe Herald editor John W. Griffen wrote. “People began moving away.”

The things they took didn’t weigh so much on the citizens’ minds as the lives that were lost, according to a November 6, 1862, letter written by Dr. Thomas Hamil to Maj. Gen. Samuel R. Curtis, commander of the Department of the Missouri in St. Louis and posted in Leavenworth, Kansas.

“I was in Olathe when Quantrill came, there,” Hamil wrote, “He took everything of wearing apparel and all the horses that he could get; he took all of my clothes, a good horse, and a fine gold watch; but we did not care for being robbed, if he had not killed our citizens in cold blood, taking our best citizens from the bosom of their families and shooting them down like so many hogs.”

Not trusting the Federal army to protect them, many townsfolk and farmers alike— including Beatty Mahaffie—moved their families away from Olathe. The town’s population dropped from 500 to about 250 almost overnight. Stores closed, and houses stood vacant. Owners offered free rent if someone would simply stay and keep watch on the property, but there were few takers. Cattle ran loose in the deserted streets.

Most residents who left Olathe stayed away until the Civil War ended, and of course, some never returned. The Mahaffies, however, spent the winter in Westport, Missouri, and returned to Olathe early the following year. They continued farming, and in the spring of 1863, began operating a stagecoach way station between Kansas City and Lawrence, while adventurers, emigrants and Americans tired of war continued the great migration west.

Mary-Lane Kamberg is the author of I Don’t Know How to Cook Book and an award-winning poet, essayist and journalist. Her humor has appeared in the Christian Science Monitor, Kansas City Star and Kansas City Parent.