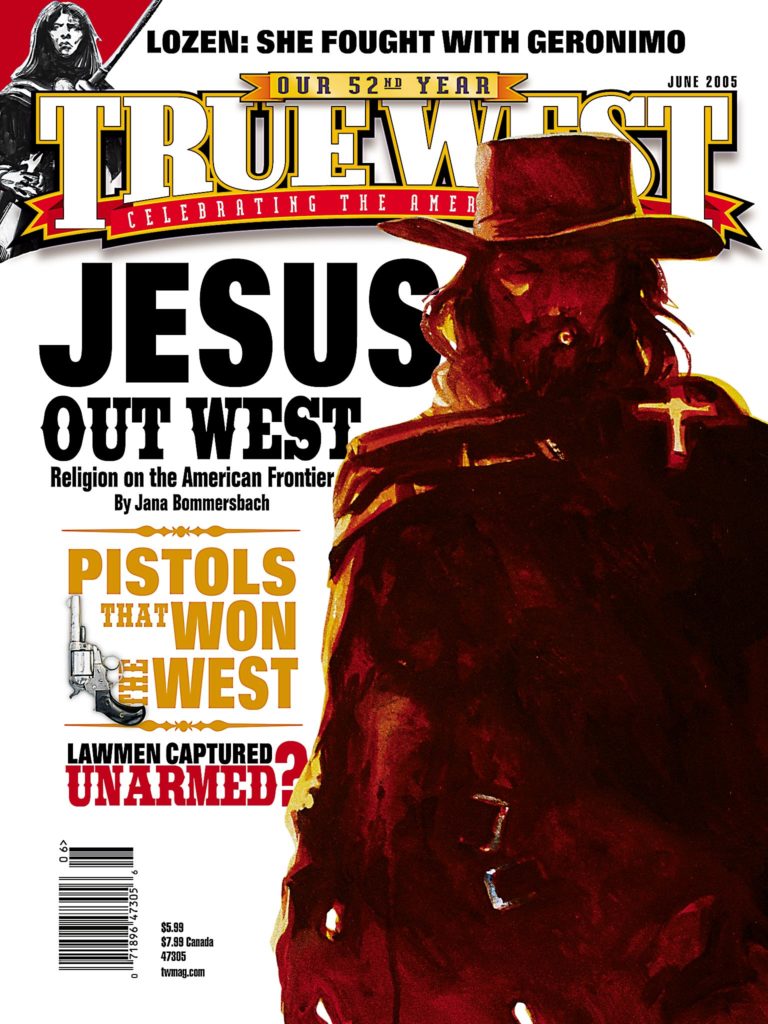

Jesus Christ immigrated to the West, too, but you could read 100 history books and never know that.

Jesus Christ immigrated to the West, too, but you could read 100 history books and never know that.

It’s impossible to talk honestly about the settlement of the West without talking about religion, but historians sure have tried.

Credit has been given to trappers, explorers, miners, the military, homesteaders and even gunslingers—everyone knows these Western icons, but few could name a single religious leader whose mark was made on the West.

“Most western communities owe far more to these unheralded clerics than they do to the high-profile outlaws or icons,” says historian Ferenc Morton Szasz of the University of New Mexico.

Or as Christian History magazine put it: “Though history has all but forgotten them, it was Christian preachers and teachers who really tamed the West.”

Christians of all Protestant persuasions made a B-line into the new territories west of the Mississippi because “Americans saw the untamed wilderness as immoral and irreligious, and men and women alike decried the lack of churches and other suitable moral and religious institutions,” explains Susan Myres in Westering Women.

Besides, the Catholics were already there—had been since the Spanish started colonizing the West a century before the Pilgrims landed at Jamestown. That only added extra fuel to the fire—Protestants despised Catholicism and feared its spread was a “threat” to the nation. (The faith was long hounded: Maryland was founded in 1632 as a refuge for Catholics, but Protestants eventually took it over. By 1775, the only colony to allow public worship by Roman Catholics was Pennsylvania.)

And the West was already populated with the religions of native people—Gods like Usen and White Painted Woman—but these nature-based sects weren’t recognized by traditional groups, either Protestant or Catholic.

Jews helped settle the West, too, especially through the “Galveston Plan” that brought 10,000 Russian and European Jews through the Texas port. And, of course, the most significant pilgrimage was one undertaken by the Mormons, who settled Utah and went on to play a major role throughout the West. (One historian has said that trying to write the story of the West without the Mormons is ignoring the hole in the doughnut.)

If you look closely, it’s easy to see why America’s religions rushed to save the West. After all, they believed America was the world’s “Savior Nation.”

The Biblical West

Even the language used to describe the West gave it a Biblical tone: It was the “promised land” or “Eden before the fall.” The discovery of gold in California was seen as a “sign of divine favor”; and journalist Louis O’Sullivan incited a nation in 1845 when he declared: “The American claim is by right of our manifest destiny to overspread and possess the whole of the continent, which Providence has given us.”

This zeal is described in Religion and Society in Frontier California, where Laurie F. Maffly-Kipp quotes a New York minister after a trip to the West: “Here is spread out before us an embryo world, and that world is to be peopled by a race of giants; but whether they will be giant-angels or giant-demons, must depend on the beneficence of Eastern churches and the grace of God.”

It’s not hard to imagine many immigrants relating to those words as they came into an uncharted, rowdy, lawless, brutal world where the only institution was the saloon.

Religion called settlers forward, even if fear had once held them back. The first Anglo women to migrate West—Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spalding—were missionary wives bringing Christianity to the Nez Perce Indians in the Walla Walla River Valley of Washington in 1836.

Even though Narcissa and her husband came to a horrible end, massacred in 1847, her legacy would inspire other women to venture into the unknown of the vast western lands, starting a migration that was like opening a floodgate.

By then, Maffly-Kipp notes, there was “hysteria” over Catholicism. She says people “imagined that a papal plot was afoot to populate the West in order to gain political control of the area, at which time Catholics would rise in armed revolt and establish ‘popery and despotism’ in America.”

Prejudice wasn’t reserved for the Catholics, however. Mormons had been hounded out of the East by objections to their belief in polygamy, but also because they were seen as an economic threat—sticking together, buying from one another, controlling the economy of an area to the detriment of others. Historian Myres reports that feelings were so negative toward Mormons that emigrating Eastern women held everyone, including minority groups, in higher esteem. And Native Americans’ religions were not seen as religions at all but as the mumblings of “heathens.”

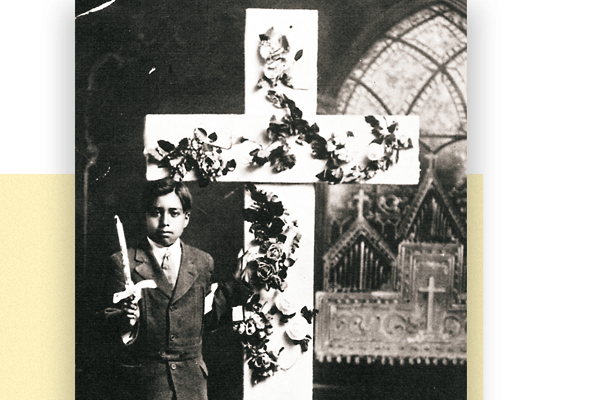

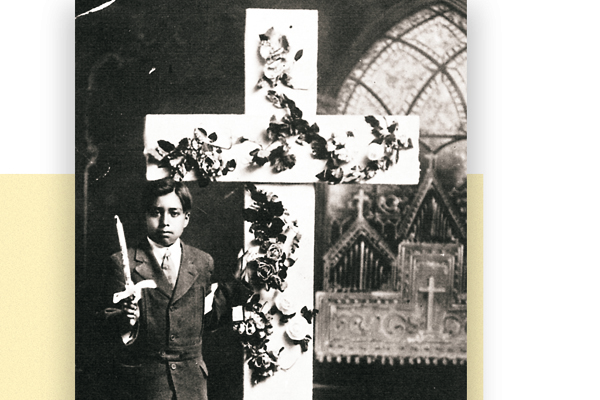

While the immigrants brought their beliefs and prejudices with them, historians note the open West also seemed to open some minds. After all, the West was not only the most diverse region of the nation—holding the most Hispanics, most Asians and most Native Americans—but it also was the new home of foreigners immigrating for the second time. By 1870, nearly three in 10 Westerners were foreign born, and many came with their own religions: the German Lutherans and German Methodists, the Dutch Reformed, the Eastern Orthodox and the Icelandic Lutherans, notes Wyoming historian Carl V. Hallberg. (German Lutherans, praying in their native language, hoped English speakers were just as pious.)

More than gold

The discovery of gold in California in 1848 was the first major turning point for the West, drawing thousands of men who thought they’d find the end of the rainbow.

But most of the immigrants who’d make deep ruts in the Oregon and Santa Fe Trails didn’t come to get-rich-quick. They came to settle down, to make a town, to make a community and to make a new life in a land of opportunity.

Getting to the West was a religious-challenging experience. Although some wagon trains insisted they’d never travel on the Sabbath, that oath often went by the wayside when the reality of the trip hit home. More likely, people would bemoan, “there is no Sunday west of Kansas City,” as weary wagon trainers were forced to put their “day of rest” on hold.

It’s a sure bet, though, that as they discarded precious keepsakes along the way to lighten their load, they never left the family Bible behind. Just as it was likely to find in a pioneer home a handmade quilt carrying a religious pattern, like Jacob’s Ladder or the Cross and Crown.

In her look at the frontier experience from 1800 to 1915, historian Myres notes how quickly religious ways took hold: “Once their homes were established, pioneers looked to the building of schools and churches, as the necessary next step in banishing wilderness and taming the frontier. Women’s diaries contained frequent references to the establishment of schools and churches and their reminiscences were replete with descriptions of the first school, the first Sunday school class, the first preacher and the first church building.”

She tells how aggressive they were to cement religion in their new world: “Pioneers were not the kind to wait for the Lord to build churches and bring ministers to the wilderness. Until a community was prosperous enough to build a church and pay a preacher, frontier settlers relied on Sunday schools, singing meetings, and other informal, lay-led activities supplemented by itinerant preachers and camp meetings to fulfill their religious needs.”

Those actions were not just pious, but prudent, Dr. Szasz tells True West. “The west had no institutions per se—the churches provided the institutions: the hospitals, schools, orphanages, old-age homes and colleges. The state would eventually take them over but at the start, it was the churches. The railroads donated land to the churches because churches meant stability.”

In fact, realtors and civic leaders would highlight their ministers and churches as marks that their community was “mature.”

From the start, the role of school and church were intertwined. “During the 1830s, Catherine Beecher, backed by the American Lyceum, began a campaign to send as many as 90,000 female teachers to the West to ‘civilize and Christianize’ raw frontier communities,” Myres notes.

Western journalism also must give its due to religion. An American Studies article notes that “many men of religious conviction were quick to found frontier newspapers under the assumption of spreading the word of God to people who, for the most part, were leading a fairly secular existence.” These editors relied on the “thirst for the written word” to present articles that were “equal parts sermon and news.”

None of this much impressed the Native Americans who were being squeezed out of their land—land on which they based their spirituality. The Apaches did not see the new land-grabbing immigrants as religious people; they sneered at the “Jesus Way of the White Eyes.”

The alternatives

Mainstream religions weren’t the only ones who saw the West as a land of milk and honey. Elesha Coffman of Christian History magazine notes that many non- and semi-Christian groups also laid claim to the West. It seems not to be an accident that free-thinking colonies were established in the free-wheeling West.

By 1897, California had the Point Loma Theosophical colony to lead its followers on the path to “truth and light.” Freethinkers established Liberal, Kansas; socialist utopias were found in Puget Sound and California; New Thought—an offshoot of Christian Science—was found in Kansas City, Denver and Los Angeles.

But, of course, none of these were as significant as what Coffman calls “the most successful religious experiment”—the Mormons.

Joseph Smith had founded this religion in Ohio, but the Mormons were driven out; they settled in Illinois, where Smith was murdered in 1844. His successor, Brigham Young, moved the church west for survival. Their goal was to establish a church-run state that would eventually be admitted to the United States. They called it Deseret, after a word for honeybee, that symbolized the cooperative nature of Mormonism.

“Deseret was a paragon of organization and ambitious growth,” Coffman writes. “The church’s Perpetual Emigrating Fund paved the way for Saints from Eastern and Midwestern states, as well as converts from European mission fields, to join the Great Basin community.” Young also sent family groups to establish other communities throughout the West. By the time he died in 1877, more than 135,000 Saints were living in the promised land.

Coffman notes that non-Mormons disdained the church not only for polygamy but also because it was such a success: “because it was so powerful and growing so quickly.” Under pressure from the federal government, Mormons outlawed polygamy in 1890 and were rewarded with Utah Statehood. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has continued to grow—it’s now called the fastest growing religion in the country—and is a powerful political influence throughout America.

Billy the Kid and a religious war

You are truly an aware student of history if you realize the Lincoln County War was a religious fight.

The story begins with ex-soldiers who decided to stay in New Mexico after their enlistments were up. The group included Irish Catholics Jimmy Dolan, Lawrence G. Murphy and John Riley. They started a mercantile business to sell supplies to the army, using their old connections. It was a beautiful, cozy deal. They became known as the Santa Fe Ring that eventually controlled all the army contracts.

But here comes competition on every front: a couple of educated and haughty Protestants, John Henry Tunstall and Alexander McSween, who can’t stand those drunken, Pope-ring-kissing Catholics. They open their own mercantile to compete, certain they can best the “Micks.” This could be considered one of the most severe cases of underestimating your enemy in the history of the West: The Catholics kill Tunstall and McSween and take over their business and their ranch.

Into this mess comes Billy the Kid, himself an Irish Catholic—but with surprising lack of religious commitment. He sided with the Protestants against his own. He didn’t have long to run before he’d be dead himself.

To this day, the Catholic influence in New Mexico is dominant.

Everything that’s new is old

It’s surprising to learn some of today’s popular religions notions came from those early Western days.

The country song that compares the Bible to a deck of playing cards came from a sermon in a Clifton, Arizona, saloon in 1899, Dr. Szasz notes. And the question, “What Would Jesus Do,” was first posed in the 1896 book, In His Steps written by Congregational Minister Charles Sheldon. Dr. Szasz points out the book is still in print.

History may have tried to ignore the role that religion played in taming the West, but the truth is there for all to see.