Researching the life of Martha Canary, better known as Calamity Jane, was a challenge.

Researching the life of Martha Canary, better known as Calamity Jane, was a challenge.

Disproving claims that she was a scout and a pony express rider, and that she captured Jack McCall after he shot Wild Bill Hickok was difficult enough. Tougher yet was locating reliable sources telling what she was like, when she lived where, and what she did for a living. This was especially difficult since she could not read or write, leaving no personal record of her activities.

The solution to these problems was simple: hard work and patience. Because newspapers, once Martha became well known, reported her movements and occasionally interviewed her, it was essential to read all the papers between 1875 and 1903 (her adult years) in South Dakota, Wyoming and Montana, as well as from some other places. Most of these were available only on microfilm, and it took several years to read them; often, I found nothing at all for days at a time. However, I eventually developed a chronology of her life. Also, I found several important interviews by reporters who met her. Along the way, essential documents, such as census reports, marriage licenses and court records, were located.

From these documents, it was obvious that many stories circulating about Calamity Jane were false. The so-called Diary and Letters of Calamity Jane, produced by Jean McCormick in the 1940s, claiming that Calamity and Wild Bill were married and had a daughter (Jean, of course), and that Calamity traveled with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, contradicted the historical record. On the other hand, many details in the Life and Adventures of Calamity Jane, By Herself turned out to be true. Newspaper reports, in fact, proved that Martha told the stories in her Life and Adventures, and had them printed to sell to dime museum audiences in 1896.

Patience brought further rewards. Friends, doing their own research, shared items they located about Calamity Jane. One sent the marriage record of Martha’s parents; another, the marriage certificate of Martha and Bill Steers; and yet another, an important interview with Calamity from an obscure magazine.

The Calamity Jane that emerged from these records contrasted with the woman described in popular stories. Instead of wearing men’s clothing and being a stage driver, pony express rider or gunfighter, Martha mostly wore a dress and worked in occupations expected of 19th-century women: laundress, waitress, dance hall girl and prostitute. Except for trips as a camp follower with military expeditions in 1875-1876, her buckskin outfit evidently was worn only during stage presentations and saloon performances.

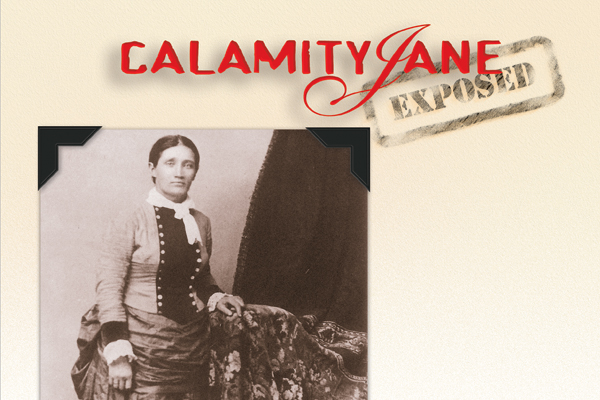

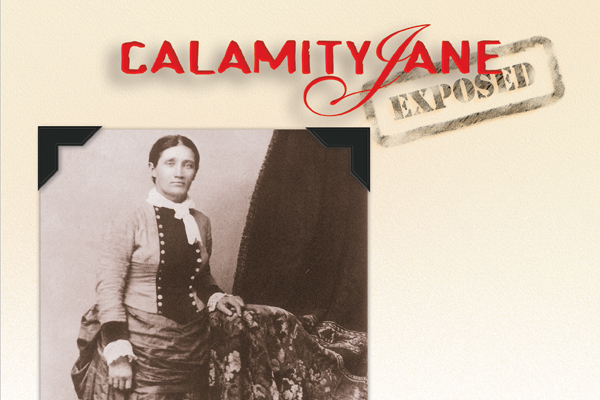

Photographs confirm these accounts. Two early pictures show Martha wearing the buckskin outfit of a scout: one was taken in 1875 when she was a camp follower with the Jenney expedition into the Black Hills; the other, in 1876-77 in Deadwood, perhaps in the outfit she wore as she entered the mining camp with the Hickok party. Most other pictures of Calamity wearing men’s clothing are studio photographs taken in Deadwood or the Livingston, Montana, area, between 1895-1898, to sell to admirers and audiences. In contrast, snapshots taken of Martha by amateur photographers show her wearing a dress as she moved from town to town through the northern plains. These depict the actual Martha Canary, contradicting the staged photographs showing the Calamity Jane of legend.

James D. McLaird is a professor emeritus of history at Dakota Wesleyan University. After meticulously researching Calamity Jane for over 20 years, he’s written Calamity Jane: The Woman and the Legend, released by University of Oklahoma Press in September 2005.